Optimism as Cuba set to test its own Covid vaccine

- Published

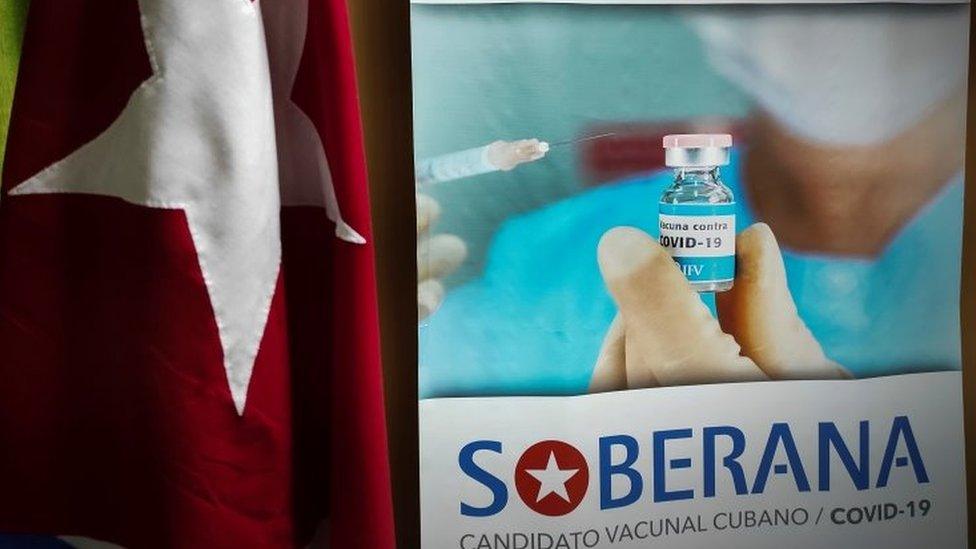

Cuban scientists are working against the clock on their Soberana 2 vaccine

Some of the equipment at the Finlay Institute of Vaccines in Havana might be considered outdated elsewhere in the world but the science taking place behind its white-washed walls is cutting edge.

Researchers are working long shifts on Cuba's best shot to solve its coronavirus crisis: Soberana 2, the island's domestically-produced Covid-19 vaccine.

Soberana (Spanish for "sovereign") 2 is a conjugate vaccine - meaning an antigen is fused to a carrier molecule to bolster the vaccine's stability and effectiveness.

Within weeks, it will be tested on tens of thousands of volunteers.

Vicente Vérez Bencomo says the results from the first trials have been encouraging

The results from the first clinical trials were "encouraging" and "very important", says the institute's director, Dr Vicente Vérez Bencomo, and the Communist-run government hopes to give the vaccine to everyone on the island by the end of the year.

"Our plan is to, of course, first immunise our population," explains Dr Vérez at a news conference. "Moving to commercial production of Soberana 2, we're planning to have in the order of 100 million doses during 2021 and we will dedicate an important part of these doses to the full immunisation of the country."

No US role

It is an ambitious goal but a realistic one as Cuba has more than 30 years of experience in biotechnology and immunology.

Cuba is not new to the development of vaccines

In the late 1980s, Cuban scientists produced the first meningitis B vaccine and the then-leader, Fidel Castro, opened the Finlay Institute partly with a view to finding ways around the decades-old US embargo on the island.

If patents from US pharmacological companies would not be available to Cuba, it would find its own solutions in that field, he reasoned.

However, it remains beyond the island's production capacity to make 100 million doses of the vaccine without some form of international assistance.

Still, even if the US government under President Joe Biden reverses the hard line former President Trump took towards Cuba, the US will not play a role in producing Soberana.

"Our main contacts are with Europe and Canada and we have people participating from Italy and from France," Dr Vérez explains, adding that "unfortunately" at this point there is no US participation. "We hope in the future it will be possible to move to the next step in co-operation," he says.

International bodies like the Pan-American Health Organisation (PAHO) hope that Cuba will become the first Latin American country to produce its own vaccine.

Dr José Moya shares the Cuban scientists' optimism

"We're very optimistic," says PAHO's representative in Cuba, Dr José Moya. "We've been kept informed since the pilot phase of Soberana 2 and during the experimental trials, and we've known that Cuba has been investigating the viability of several vaccines since August last year."

Healthcare under strain

The stakes for Cuba are high. Firstly, its own Covid-19 statistics are worsening by the week.

Confirmed cases recently climbed to more than 1,000 a day for the first time since the pandemic began. While those figures are tiny compared to those in Mexico, Brazil and the US, they are still serious enough to place additional strain on Cuba's creaking healthcare system.

By the middle of last year Cuba had largely contained its outbreak through a combination of an aggressive public information campaign and the closure of its airports. In July and August, there were several consecutive weeks of minimal transmission and very few deaths.

But cases have gradually crept up again, much to Cubans' frustration.

Dr Moya of the Pan-American Health Organization says the situation is not out of control and mirrors that in other countries. "There came a moment in all our countries when you had to start to reopen. And that's what happened here, as they tried to progressively move towards the so-called 'new normal'."

Short-term pain

But Cuba is currently experiencing its worst economic outlook since the end of the Cold War so there is also an important economic incentive to a successful vaccine.

The coronavirus lockdown has been very painful for an island so dependent on tourism with the economy contracting a whopping 11% last year.

Long lines form every day outside food shops and supermarkets as people queue for basic goods.

Cubans often have to brave long queues to buy food

The government has chosen this moment to implement a number of overdue reforms, from unification of Cuba's tangled dual currency system to some liberalisation of self-employment licences.

While those steps may eventually strengthen Cuba's troubled economy, they spell short-term pain for many families, especially those without relatives sending remittances from abroad.

Cubans are very resilient and resourceful - they have had to be to face the twin challenges of US sanctions and the state's overbearing control. But many are exhausted at the relentless months of coronavirus restrictions and the grinding economic hardship.

A ray of hope?

With children still out of school, businesses going bust and a curfew in place across Havana, people long for some encouraging news about vaccination.

Everyone is hoping for good news on the vaccine front

A viable vaccine would allow the island to reopen sooner and with more certainty than before. Soberana 2 would also generate some much-needed income if exported around the region.

It all places real urgency on the scientists working on it, not only to alleviate the island's health crisis but its economic one, too.

You may also be interested in:

WATCH: Pfizer v Oxford v Moderna – three Covid-19 vaccines compared