Covid-19: Brazil surge reaches new level as daily deaths pass 2,000

- Published

One epidemiologist in Brazil fears the country is "becoming a threat to global public health".

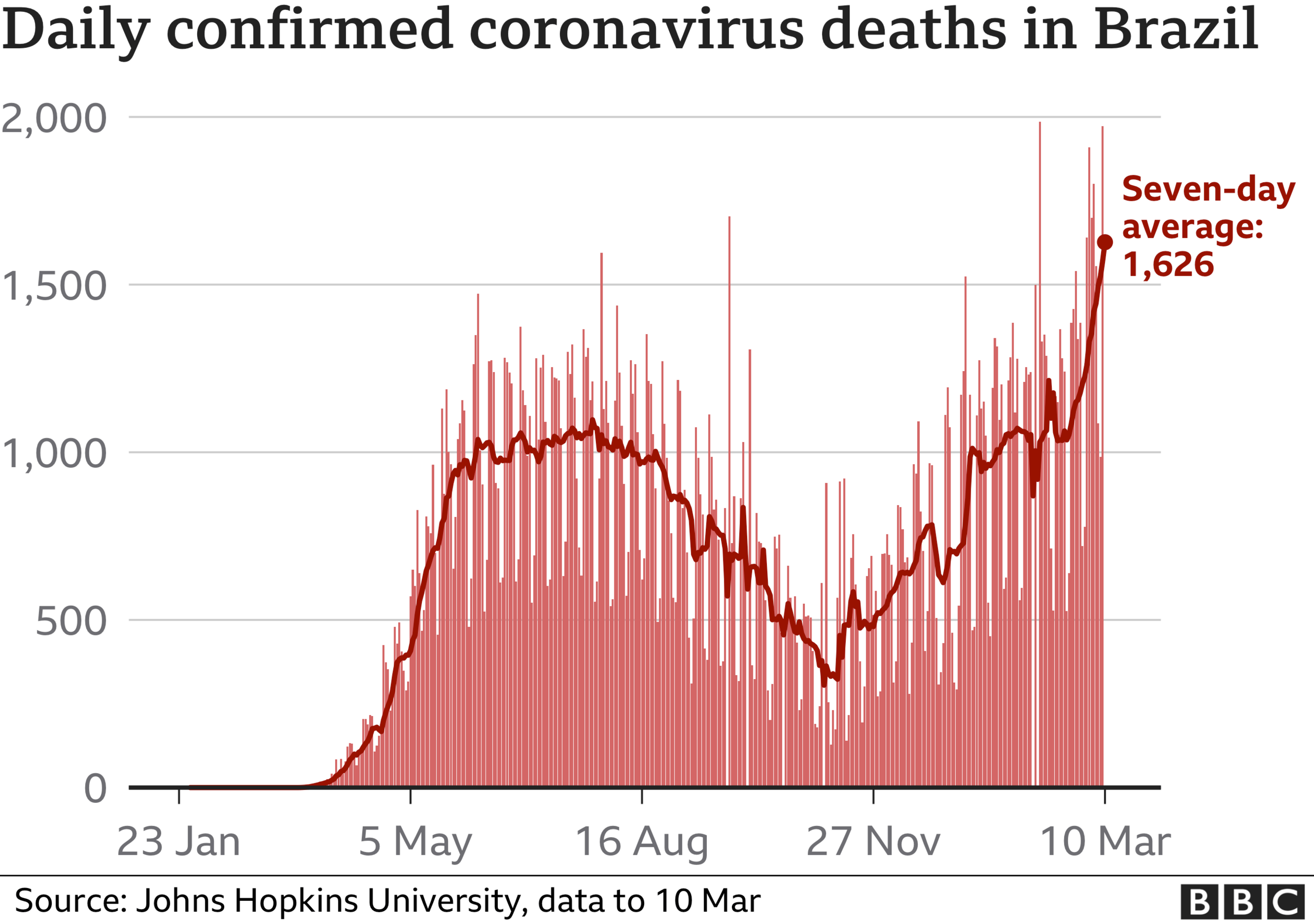

Brazil has exceeded 2,000 Covid-related deaths in a single day for the first time, as infection rates soar.

The country has the second highest death toll in the world, behind the US. Experts warn the transmission rate is made worse by more contagious variants.

On Wednesday, former leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva hit out at President Jair Bolsonaro's "stupid" decisions.

Mr Bolsonaro has downplayed the threat from the virus. Earlier this week he told people to "stop whining".

On Wednesday, the country recorded 79,876 new cases, the third highest number in a single day. The total number of Covid-related deaths reached 270,656, according to Johns Hopkins University in the US.

It means Brazil has a rate of 128 deaths per 100,000 population - 11th highest amongst 20 of the worst affected countries in the world. The highest rates are in the Czech Republic with 208 deaths per 100,000 people and the UK with 188 deaths per 100,000 people, Johns Hopkin's figures suggest, external.

What's the situation in Brazil's hospitals?

Margareth Dalcolmo, a doctor and researcher at Fiocruz described the situation as "the worst moment of the pandemic in Brazil".

Across Brazil, intensive care units (ICU) are at more than 80% capacity, according to Fiocruz. And in 15 state capitals, ICUs are at more than 90% capacity, including in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, external.

Reports say the capital Brasilia has now reached full ICU capacity, while two cities - Porto Alegre and Campo Grande - have exceeded capacity.

In its report, Fiocruz warned that the figures point to the "overload and even collapse of health systems".

Brazilian epidemiologist Dr Pedro Hallal told the BBC World Service's Outside Source programme: "If we do not start vaccinating the population here very soon, it will become a massive tragedy."

Dr Hallal, who works in Rio Grande do Sul, also said that people felt "abandoned by the federal government".

"It took a long time for the politicians to act," 40-year-old Adilson Menezes told AFP news agency outside a hospital in São Paulo. "We are paying for it, the poor people," Mr Menezes said referring to the state of near collapse of Brazil's public healthcare system.

Brazil is facing its biggest crisis since the pandemic began - but still, it feels like people are trying to ignore it.

Take São Paulo for example; while non-essential shops have had to close these past few weeks, there's no "lockdown" to speak of - no restrictions on whom people meet and schools have remained largely open (albeit with lower capacity).

People here are making their own decisions about how to stay safe, and there certainly isn't that fear like we saw this time a year ago, where the whole world was shutting down, so Brazilians did the same.

A year on, and even amid dire statistics that are set to carry on rising, Jair Bolsonaro's narrative has been bought by many - a mistrust of the Chinese CoronaVac vaccine, a railing against closing restaurants and businesses - all the while, scientists are increasingly calling for more national leadership to stop the entire health system from collapsing in the coming weeks.

What's behind the surge?

A surge in cases in recent days has been attributed to the spread of a highly contagious variant of the virus - named P1 - which is thought to have originated in the Amazon city of Manaus.

Preliminary data suggests the P1 variant could be up to twice as transmittable as the original version of the virus.

It also suggests that the new variant could evade immunity built up by having had the original version of Covid. The chance of reinfection is put at between 25% and 60%.

Scientists are concerned that Brazil has almost become a "natural laboratory" - where people can see what happens when coronavirus goes relatively unchecked.

Some warn the country is now a breeding ground for new variants of the virus, unhindered by effective social distancing and fuelled by vaccine shortages.

That's because the longer a virus circulates in a country, the more chances it has to mutate - in this case giving rise to P1.

Global experts are calling for a plan - including rapid vaccination, lockdowns, and strict social distancing measures - to get the situation under control.

The worry is that the P1 variant is a looming threat over the progress made in the region and the wider world.

Current vaccines are, on the whole, still effective against the variant but may be less so than against the earlier versions of the virus they were designed to fight.

Studies are ongoing but experts will get their most robust understanding of how well these vaccines work against P1 as they continue to monitor people who have been vaccinated in the real world.

Scientists are confident that, if necessary, vaccines can be tweaked fairly quickly to work against new variants.

Last week, the Fiocruz Institute said P1 was just one of several "variants of concern" that have become dominant in six of eight states studied by the Rio-based organisation.

The director of the Pan American Health Organization, Carissa Etienne, said the the situation in Brazil "provides a sober reminder of the threat of resurgence: areas hit hard by the virus in the past are still vulnerable to infection today".

How has the government reacted?

President Jair Bolsonaro has belittled the risks posed by the virus from the start of the pandemic. He has also opposed quarantine measures taken at a regional level, arguing that the damage to the economy would be worse than the effects of the virus itself.

President Bolsonaro dismissed the criticism levelled against him

His stance has come in for severe criticism both internationally and in Brazil itself.

Mr Bolsonaro's former ally turned political rival, João Doria, has called the the president "a crazy guy".

São Paulo Governor Mr Doria has described President Jair Bolsonaro as a "crazy guy" who is making the country's coronavirus situation worse

On Wednesday, former President Lula, in his first speech since corruption convictions against him were annulled, told people not to follow "stupid" decisions by Mr Bolsonaro and to "get vaccinated". Lula said "a lot of deaths could have been avoided".

Responding to Lula's scathing remarks, Mr Bolsonaro said his government had done enough to fight the disease.

- Published10 March 2021

- Published10 March 2021

- Published5 March 2021

- Published19 February 2021