The labels encouraging Chileans to buy healthier food

- Published

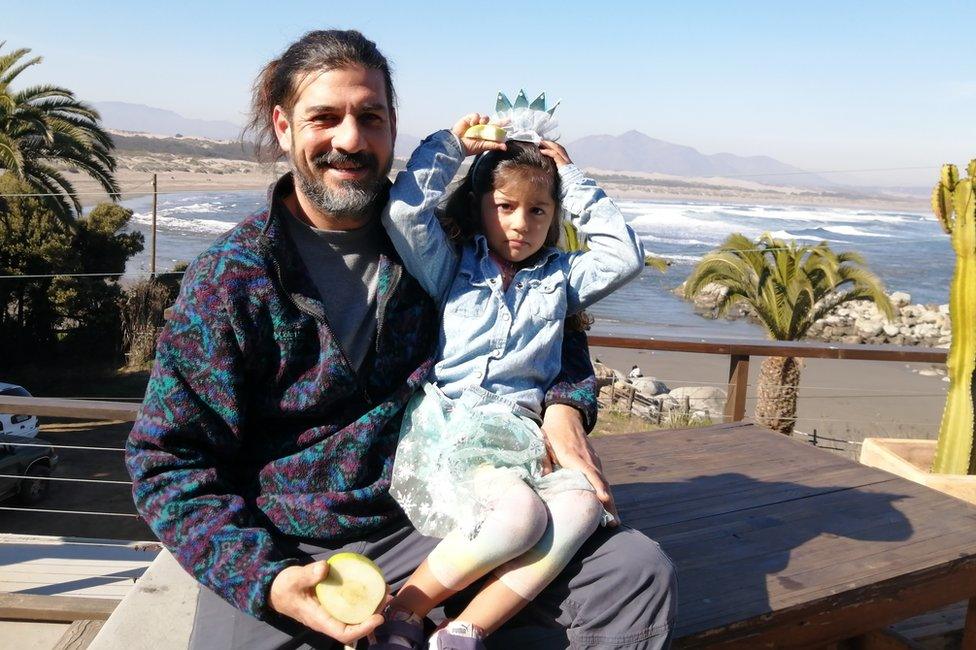

Rosa Cayso Phocco says the warning labels have made her change her habits and leave the biscuits behind

Faced with what experts described as a "health time-bomb", Chile in 2016 introduced food labels to warn consumers of high saturated fats, sugar, or salt to tackle high obesity rates. Five years on, have they worked?

Macarena Rivera Zurnovsky is a mother of three children who says she has always wanted to buy what is best for her family's health.

She says the warning labels provide useful guidance and have stopped her from buying products - including certain breakfast cereals - which she thought were healthy but now knows are not.

That experience, she says, has also made her more cautious about the ingredients that go into the food she buys and she now checks the back of the packet to see what is in it.

It is a view echoed by Rosa Cayso Phocco, who says the labels have "helped me think more carefully about what I buy for my son" on trips to her local supermarket in the capital Santiago.

"These days I prefer to leave the biscuits and buy him things like yoghurt or porridge oats instead," she adds.

Diego Arenas Donoso has always tried to eat as little processed food as possible. He generally buys his food from the local market and cooks for himself and his family from scratch.

Diego Arenas Donoso would have liked the Chilean government to be bolder

He thinks the government was too cautious when it introduced the labels. Mr Arenas thinks the labels would have been more effective if they had been red in colour - indicating danger - rather than the more subdued black.

Have the measures reduced obesity rates?

In 2016, almost three quarters of people living in Chile aged 15 and over were either obese or overweight, according to a report [in Spanish] by Chile's health ministry, external.

The situation among those under 15 was also very worrying, with 51.2% of school children either obese or overweight.

But despite the changes in shopping habits of mothers like Ms Rivera and Ms Cayso, the figures for school children who are overweight or obese appear not to have been impacted.

In fact, they have crept up from 51.2% in 2016 to 52% in 2019 and 54% in 2020.

Daniela Godoy from the government organisation Eligir Vivir Sano (Choose to Live Healthily) says the Covid pandemic is to blame for the latest two-percentage-point jump.

"Sitting for long hours in lockdown has made the fight against obesity much more of a challenge," she says.

Most children in Chile have been attending classes online since the start of the pandemic in March 2020, and both children and adults have been turning to highly processed fattening foods like pizza and biscuits to cheer themselves up while they sit at home, Ms Godoy explains.

With the government urging people to stay at home to prevent the spread of the coronavirus, it has also been hard for many who lack the space to exercise.

Coronavirus restrictions made it hard for children to get exercise

And while the changes were introduced five years ago, some unhealthy habits have proven hard to break.

Chileans' love of sugary drinks is one of them, says Daniela Godoy. The average household of 3.3 people is buying more than 23 litres every month, according to a 2021 government study.

Many Chileans are also moving away from preparing traditional home-cooked meals and eating fruit and vegetables to consuming more fast food and snacks.

But despite the setbacks, María Paz Grandón, who works in public policy for Chile's health ministry, is convinced that the changes introduced in 2016 are having a positive effect.

She insists that the labels not only act as an easy-to-understand warning signal for consumers, they have also prompted some in the food industry to make changes.

The labels warn of a high calorie, high saturated fat and high sugar content

She says that in order to avoid having a label slapped on their products marking them as high in saturated fats or high in sugar, some food manufacturers are modifying their products to make them healthier.

And according to Ms Grandón, it is often the children themselves who are driving the change in shopping trends.

In focus groups, parents have reported that their children tell them off when they reach for sugary, fatty or salty options in the supermarket and even "pester" them to go for the healthier choices. The parents think this is down to what the children have been taught about nutrition in school over the past years.

Ms Grandón thinks that the ban on TV advertisements for unhealthy foods between 06:00 and 22:00 has also helped because children "no longer opt for a sugary cereal because it features a cartoon character" they have seen on TV.

But Daniela Godoy insists that in order for obesity levels to be driven down more will need to be done and everyone will have to pitch in. "The food industry, different government ministries, schools and parents will have to play their role."

María Paz Grandón from the health ministry says the government is already considering widening its approach.

Possible measures include requiring restaurants to display how many calories each dish has and thinking about urging supermarkets to remove salty and fatty snacks from the check-out areas.

Mr Grandón points out that just as the government did with the labelling laws, any changes would be implemented gradually to give the industry time to adapt.

Related topics

- Published30 May 2019

- Published27 July 2020

- Published15 January 2021

- Published23 December 2020