Children's home fire: 'The souls of our daughters are still there'

- Published

Ashly died in a fire at a children's home in Guatemala along with 40 other teenage girls

Vianney Hernández remembers how powerless she felt on the day in December 2016 when a gang came to take away her 13-year-old daughter Ashly.

Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of injuries and strong language.

Its leader, who was in a relationship with Ashly, threatened to kill the entire family if she did not let Ashly go live with him.

Ashly had met the boy at school in a poor neighbourhood of Guatemala City where they lived. "He was handsome, a bit older than her," Ms Hernández recalls, adding that her daughter was rebellious and with an appetite for adventure.

Vianney was determined to wrest Ashly from the hands of the gang. She told the police, and after they found Ashly, Vianney sent her to a state-run home for at-risk children so she would be far away from the boy and his gang.

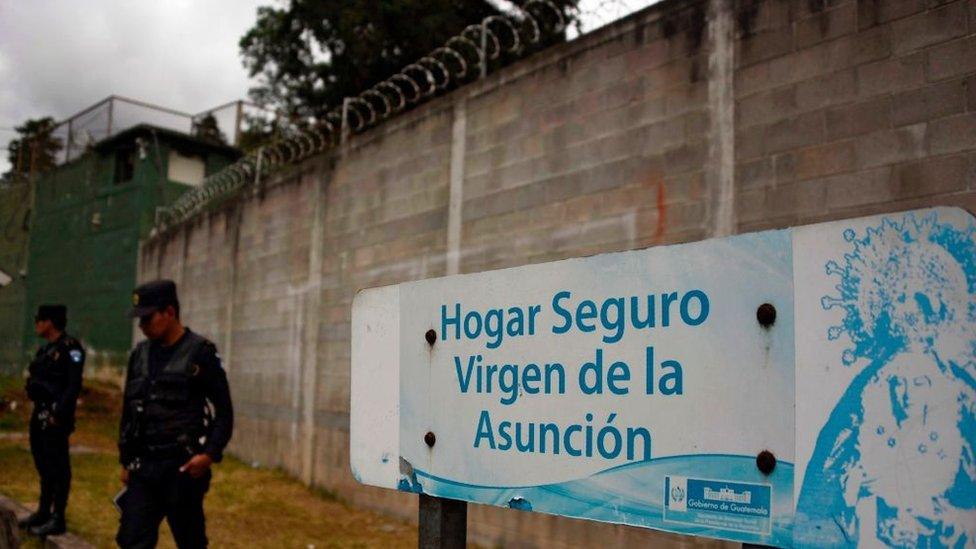

Ashly had been to the home once before and Vianney knew that the rosy picture officials painted of the Virgen de la Asunción home in San José Pinula was far from the truth.

The outside of the home resembled a prison more than a shelter

Before Ashly's first stint in the home, Vianney had been told that her daughter would get food, clothes, an education and psychological care.

Instead, "supervisors would send older girls to beat Ashly up and when she resisted, they would punish her," Vianney recalls.

The home was overcrowded and dirty, and the food was often spoiled. But with the gang unlikely to leave Ashly in peace, Vianney thought that sending her daughter back to the Virgen de la Asunción home would be the lesser of two evils.

Otherwise, "one day I would find her dismembered body on my doorstep", Vianney says of her fears at the time.

Like Vianney, many families sent their children to the home with the best of intentions, unaware of the criticism it had come under from organisations in Guatemala and abroad, including the United Nations, external and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.

Some parents suspected that something was amiss at the home but did not know the full extent of the abuse.

Sixteen-year-old Mirsa was one of the girls too frightened to speak out.

"She never told me what went on there," her mother Roxana Tojil recalls. "Once she said: 'I can't tell you anything, because they would beat me, lock me up in a dark room or leave me without food'."

Roxana Tojil (left) is among the mothers who have been attending vigils

Mirsa had been sent to the home by a judge after she escaped from the gang which had tried to forcibly recruited her. The judge reckoned she would be safer there than in the gang-controlled neighbourhoods of Guatemala City.

Too afraid to tell their parents of the conditions in the home, Mirsa, Ashly and others hatched a plan.

On 7 March 2017, they were among about a hundred children who escaped from the home.

But it did not take long for the police to track them down and return them to Virgen de la Asunción, where 56 of the girls were locked up in a classroom designed to hold 26 people.

An investigation later revealed that the girls were not even allowed to leave the room to go to the toilet. If they wanted to relieve themselves, they had to do so in a corner. In the morning, they were given breakfast in the same filthy room.

Desperate to get out, one of the girls lit a match. The flames quickly spread. The girls banged on the door in panic, but for nine minutes it remained locked.

"Let those sluts burn, let's see if they can escape again," the police officer holding the key said according to the testimony given by her subordinate officers.

Forty-one girls died, 15 others suffered life-changing injuries.

Following the fire, relatives tried to locate their loved ones

Roxana Tojil rushed to the hospital. "All the girls looked alike: bandaged, their skin carbonized. One was without lips and nose. Another one screamed: 'Throw water on me!' I saw them closing their eyes and dying."

Eventually Roxana found Mirsa. She was in the morgue, dead.

Ashly was also in the morgue but Vianney refused to view her daughter's burned body.

"I wanted to keep her beautiful in my heart, not how the State had returned her to me," Vianney says.

At the funeral, Vianney hugged the coffin. "I vowed that her death would not go unpunished," she recalls.

Many relatives called for justice (in Spanish: justicia) during the funerals for the girls

Twelve public officials are on trial, facing charges ranging from manslaughter to abuse of authority, but the victims' families say that the legal proceedings have been slow and frustrating.

Hearings were repeatedly suspended even before the Covid pandemic struck.

The judge in the case told the BBC that the reasons for the delays varied, including appeals being lodged by both parties, the temporary absence of a defence lawyer and a general work overload which meant that sometimes hearings for different cases were scheduled for the same time, resulting in the judge having to cancel one.

Vianney says she is livid that only three of the defendants are in pretrial detention with the remaining nine able to enjoy the comforts of their own homes after having been placed under house arrest. Meanwhile, she is struggling to find a job flexible enough to allow her to attend court.

The hearings have been painful for the mothers as the defence has tried to shift the blame for the deaths onto the girls, arguing that the students started the fire.

The mothers themselves have also been criticised, with some in Guatemala questioning why they would have sent their daughters to such a home in the first place.

The relatives have erected a monument with 41 crosses outside the presidential palace

Vianney wants to know what exactly went on at the home - not just in the run-up to the fire but in the years preceding it, after allegations of human trafficking surfaced.

She is also fighting for the evidence of the fire to be preserved. On 14 June she petitioned a judge to stop the classroom where the fire happened from re-opening, which would have compromised any evidence inside the room.

"The souls of our daughters are still there, calling for justice," she says, her voice breaking.

Related topics

- Published25 June 2017

- Published5 April 2017

- Published13 March 2017

- Published9 March 2017

- Published8 March 2017