'We felt free': Cubans remain defiant in face of protest crackdown

- Published

Scenes of protest like the one in July are very rare in Cuba

The unspoken rule in Cuba has long been: do not speak out.

Even during the island's dire food shortages, most Cubans have coped with characteristic stoicism, taking care that their mutterings of complaint do not grow into loud calls for change, at least not in front of anyone in authority.

But 11 July was a day unlike any other in modern Cuba.

Months of pent-up frustration bubbled over - not just over food shortages but also the lack of medicines, long power outages, worsening inflation and the coronavirus pandemic.

As the demonstrations quickly spread across the island, the specific conditions which prompted people onto the streets varied slightly from place to place - a greater emphasis on blackouts in San Antonio de los Baños near Havana, more reference to the Covid-19 crisis in the city of Matanzas.

Yet all the protests shared one common chant: "Libertad". They clamoured for liberty, freedom and change after 63 years of one-party rule.

Hundreds of people were arrested

"In that moment, saying whatever you wanted to say, you felt free. It was an experience I would recommend to everyone of my generation", says independent journalist Alfredo Martínez, who participated in the protest outside the Capitolio building, one of the most iconic buildings in Havana.

He says the fear of reprisals quickly evaporated during such an unprecedented event.

"It felt so good to finally be able to protest in our own country. It's only human to feel fear but that moved to the background because you knew you were doing the right thing - you weren't doing anything wrong or illegal."

The demonstrations were swiftly met with force as hundreds were rounded up by the police and a feared unit of elite troops called "Black Berets".

International human rights organisations say around 800 detainees are still being held, including some who are underage.

Their family members say they were given summary trials and that many were sentenced without a defence lawyer present.

The Black Berets are a feared special unit of the police

The Cuban government insists the detainees were correctly processed under the law.

Yet the mothers of the detainees are also gradually losing their fear of speaking out.

From the way Miriela Cruz constantly wrings her hands together when we talk, it is clear that the stress is getting to her.

Her son, Dayron, was arrested by the Black Berets but she insists he was far from where the demonstrations were taking place and had "nothing to do with them".

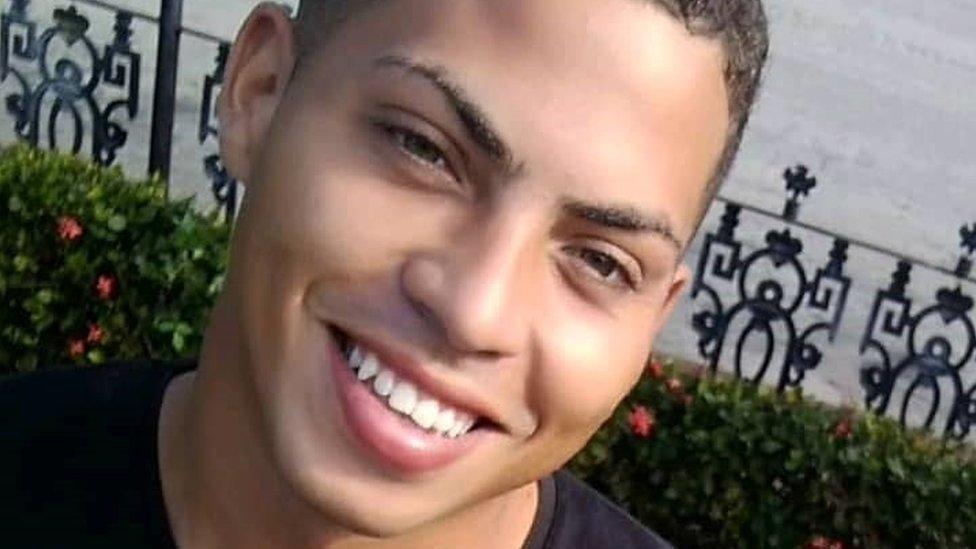

Dayron is one of many Cubans still being held in the wake of the protests

"I have no idea why he was arrested, that's the question we're all asking," Ms Cruz tells me near the hospital in Havana where she receives treatment for lung cancer.

"I'm not eating, I'm not doing well and that's not good for my illness," she says, bursting into tears.

Miriela Cruz does not know why her son was arrested

Desperate for information, she went to the police station to demand answers.

On being met with silence, she revealed a T-shirt beneath her top with the words "Down with the dictatorship!" on it.

She says she was immediately arrested, beaten and is now facing charges, too.

The Cuban government has refused to comment on individual cases but the island's leadership denies trying to make an example of the protesters.

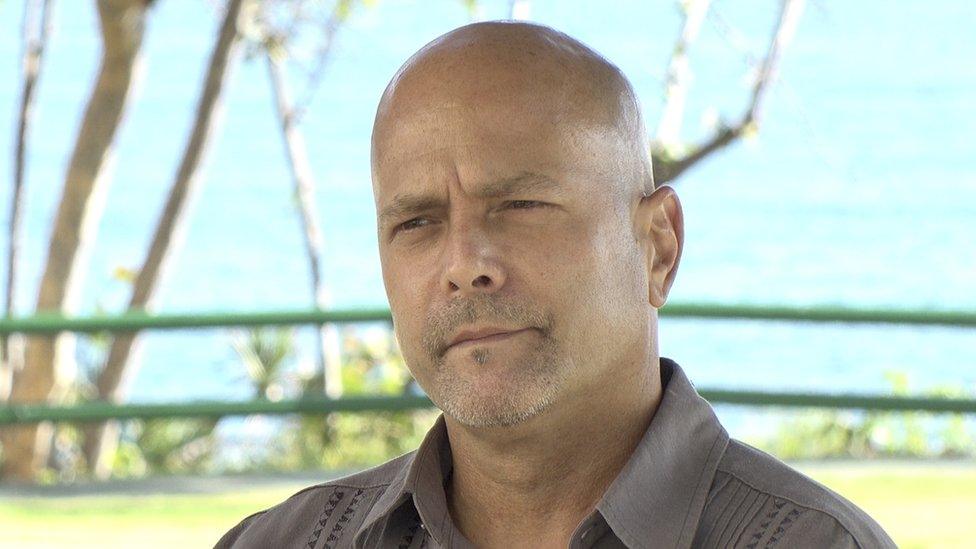

"If somebody believes that their trial was not fair, they have the right to appeal and I'm sure our system will consider their appeal. If it's true that it wasn't a fair trial, they'll have another one," says Gerardo Hernández, a member of Cuba's Council of State.

Gerardo Hernández says no prisoners are being mistreated

"As a revolutionary, as a Cuban who loves this country and believes in this system, I'm sure that's going to happen," he insists.

He also denies prisoners have been mistreated, saying, "There is no torture in Cuba, except in [the US military prison at] Guantánamo Bay where there have been some ugly cases."

Mr Hernández spent 16 years in a US prison on charges of espionage and conspiracy to commit murder. He was released as part of a prisoner swap during the brief thaw in Cuban-US relations under the Obama administration.

He is quick to blame the US economic embargo for the protests, saying Washington should "let Cuba breathe".

Read more about the protests:

Following the 11 July protests, US President Joe Biden called Cuba "a failed state".

His administration has spoken of "providing support for the Cuban people" but steadfastly refuses to lift the embargo which critics say would alleviate much of the pressure.

The US state department denies meddling in Cuba, saying the demonstrations were home-grown. "This is the moment for Cuban people," US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State Emily Mendrala told me.

"This was the Cuban people themselves making demands of their government that was driven by, in large part, exhaustion by the government's inability to meet their needs. We are clear-eyed in the US government that this moment is about them."

The mood music of constant political conflict between Havana and Washington is of little interest to Miriela Cruz, who still only has scant information about her son.

"All the strength I have left is for him," she says. "Once he's out of prison, I don't care what they do with me."

- Published18 August 2021

- Published7 August 2021

- Published22 July 2021