Mexico metro collapse: 'All I ever wanted was for my son to come home'

- Published

Brandon Giovanny was 12 when he died in the collapse of a Mexico City metro overpass

Just outside the Olivos metro station in Mexico City, there is a haunting reminder of the darkest day in the capital's transit system: a gaping hole in the overhead track of Line 12.

Thick electrical wires hang between the concrete support columns, daylight visible where the overpass once stood.

Occasionally, pedestrians glance up and shudder at the memory of the night of 3 May when two train carriages and a section of overpass came crashing down onto cars below.

There is a gaping hole where the overpass used to be

Nearby, the number 26 - the death toll - has been spray-painted onto walls by activists. Other graffiti simply reads "Justice for Brandon".

Brandon Giovanny lived locally. At 12 years old, he was the youngest victim as he travelled home on the train with his father. "I sometimes have to pass the scene [of the accident]," his mother, Marisol Tapia, tells me, her voice breaking.

Her awful, desperate search for Brandon in the rubble was broadcast around the world as she pleaded with the authorities for help.

Around 18 hours later, after her husband had been found injured in hospital and she had been repeatedly told there were no children among the dead, her son was eventually confirmed as one of the victims.

Brandon was one of the 26 who did not survive the collapse

Today, one wall of Ms Tapia's living room is entirely dedicated to pictures of Brandon, and an altar to the boy occupies another corner.

"To see his empty bedroom, to see children returning to classes without him, his birthday is coming up and my son isn't here," Ms Tapia explains, tears streaming down her cheeks.

"These are things that the government doesn't understand, they don't realise the pain they caused us that night. No compensation will bring back my son."

Ms Tapia is struggling to get through her days. Just waking up, getting dressed or making coffee takes a superhuman effort amid her gnawing grief.

Every day is a struggle for Marisol and her family

And yet, in that emotional state and from her tiny home in an impoverished neighbourhood, she intends to take on some of the richest, most powerful and influential people in Mexico.

Asked who she blames for Brandon's death, Ms Tapia's tears momentarily dry up and her voice takes on a harder, colder tone.

"Marcelo Ebrard, Miguel Ángel Mancera and Claudia Sheinbaum," she replies without hesitation. They are the previous two mayors of Mexico City and the current one.

The collapse caused anger and triggered accusations of negligence

Ms Tapia recently brought charges of negligent homicide against them. The BBC approached all three for comment but was told that none would be given while the attorney general's investigation into the collapse was under way.

Marcelo Ebrard, who is now Mexico's foreign minister, vocally championed Line 12 from the start.

During his time as mayor, he was one of its biggest supporters and gave an effusive speech about his "pride" at the line's "technical capacity" at its opening ceremony in 2012.

The city government referred to Line 12 as the "Golden Line", the newest, cleanest and supposedly safest line in the network and among the "finest metro lines in the world".

Yet even as Mayor Ebrard led a group of dignitaries onto the carriages for the inaugural journey, the problems that apparently led to the collapse were present in the very construction itself.

An initial investigation by an international team of accident specialists concluded that there were serious flaws in the original construction.

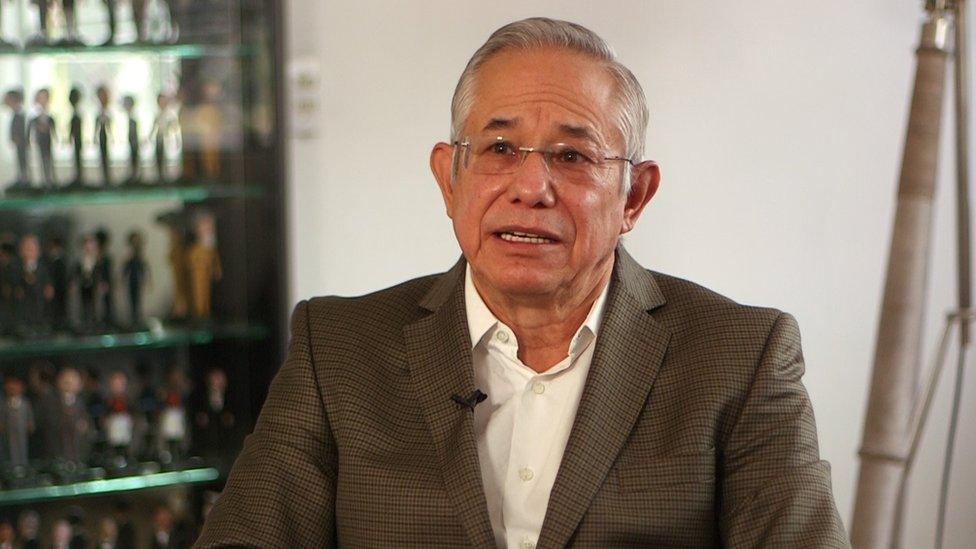

"I'd say that Line 12 was born with a cancer," says Jorge Gaviño, director-general of Mexico City's Metro system between 2015-2018.

Jorge Gaviño says the construction of Line 12 was rushed

Specifically, the accident investigation found that metal studs which connected steel beams to a concrete slab were not properly welded into place.

Critics say the workers were being rushed into finishing the project before Mr Ebrard left office. Mr Gaviño says the vast majority of the maintenance work carried out while he was the metro's director was spent on Line 12.

"It was all built in a hurry," he says. "There was a change of the original project and those changes were carried out in a rush, from the construction itself to the purchase of the trains."

So far, Mr Ebrard has declined to address those specific allegations.

Shortly after it was opened, Line 12 was closed for months for major repairs. The victims' families believe repeated warnings were ignored, particularly following a major earthquake in 2017 when some local residents say cracks appeared in the line's overpasses.

Among those under pressure over Line 12 is Carlos Slim, one of the richest men in the world. It was his company, Grupo Carso, which built the line.

Sitting in her breezeblock home, Marisol Tapia knows she faces an uphill battle seeking answers from some of Mexico's most powerful figures. Yet she remains undeterred.

It is very hard for families like hers to get justice in Mexico, she says. "But that's all we want. Not money or compensation, nothing else. All I ever wanted was for my son to come home."

You may want to watch:

'My dad never came home from work'

Related topics

- Published17 June 2021

- Published8 May 2021

- Published4 May 2021