López Obrador: What's behind Mexican leader's recall referendum?

- Published

Laura Gómez (left) says she is better off under the presidency of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador

Laura Gómez has been making tamales for more than 25 years.

Using her late mother's recipes, the corn-based staple is the mainstay of the family income.

Every afternoon, the cramped kitchen in their home in Villaflores in south-east Mexico turns into a production line of thick yellow-maize mixture wrapped in banana leaves.

For years, the business was suffocating. A day's sales of tamales barely covered the cost of ingredients for the following day's batch.

But, financial help introduced by the government of President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has granted Ms Gómez some breathing room.

"We have a small business loan, which we pay back at the rate of about 500 pesos ($25; £20) a month," she says.

The government's soft loan, which does not carry penalties for late payment, means Ms Gómez has been able to buy enough maize flour for the entire year.

Little wonder then that she will back the president, who's known as Amlo, in Sunday's mid-term recall referendum.

Unprecedented move

The referendum is unprecedented. In Mexico, presidents serve a single six-year term in office. But since before he took up office in 2018, Amlo has promised to give voters a chance to remove him from office half-way through his term.

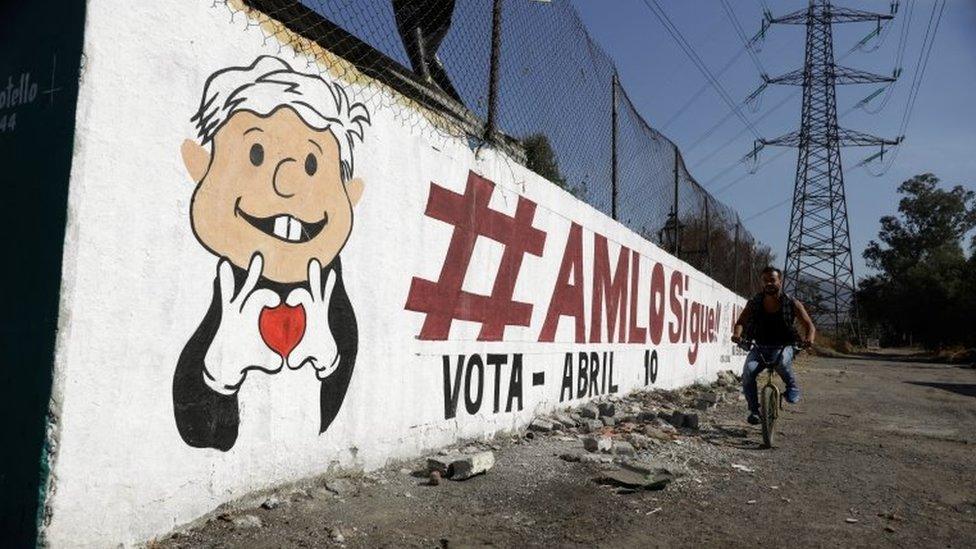

Murals have sprung up in Mexico City to try to entice people to back the president in the recall referendum

The president argues the referendum is vital to validate his democratic mandate.

More than three years into his term, Amlo still commands impressive popularity rates of around 60% despite criticism from his opponents over his handling of the coronavirus pandemic, inflation, a controversial energy reform and the drug war.

But enthusiasm for the referendum is low and only his most committed voters are expected to cast their ballots on Sunday.

Amid such indifference, Amlo's biggest challenge may not be winning the vote - which seems highly likely, but getting the necessary turnout, which must be at least 40% for the vote to be binding.

'More Amlo!'

To encourage people turn out on Sunday, Amlo's party, Morena, is holding a pre-referendum event in the dusty outskirts of Villaflores.

The event was held to boost the numbers of those taking part in Sunday's referendum

As men in cowboy hats and women with their children on their laps waited patiently for a Morena representative to take to the stage, T-shirts were handed out emblazoned with the campaign's basic message: 'More Amlo!'.

No-one at the small but noisy rally would hear a word against Mr López Obrador.

And the president can certainly count on the support of every member of the Gómez family, all of whom have benefitted from his social programmes.

Laura Gómez's daughter - a single mother with a disability - gets a stipend and her father finally receives a modest pension after decades working in the fields.

One of the key criticisms levelled at the president is that he has simply bought people's loyalty - and their votes - with the aid. But Ms Gómez says the opposite is true and that social assistance under previous presidents was conditional.

"At no time has he offered handouts in exchange for votes," she insists. "In the past, you'd be threatened with 'don't vote for this candidate or we'll take your benefits away'. Not anymore. Now you just show your papers and receive your money."

Why call the referendum?

But the president is a deeply divisive and polarising figure, and many Mexicans are questioning why he is holding the referendum in the first place.

Critics of the president say he is becoming increasingly autocratic

Some 900km away, critics of the president, who have gathered in Mexico City's Reforma Avenue for a protest, think they know the answer: re-election.

They think Amlo is using the referendum as a platform from which to campaign for an end to Mexico's single-term limit.

"We don't want him to extend his mandate," activist Lourdes says over the noise of the anti-Amlo chants. "While he's in power, we want to see him attending to the urgent needs of country," she adds, echoing the concern of many who think the referendum is an unnecessary distraction.

A protester held up a sign reading "you finish, and you leave" in reference to fears Amlo may want to run again

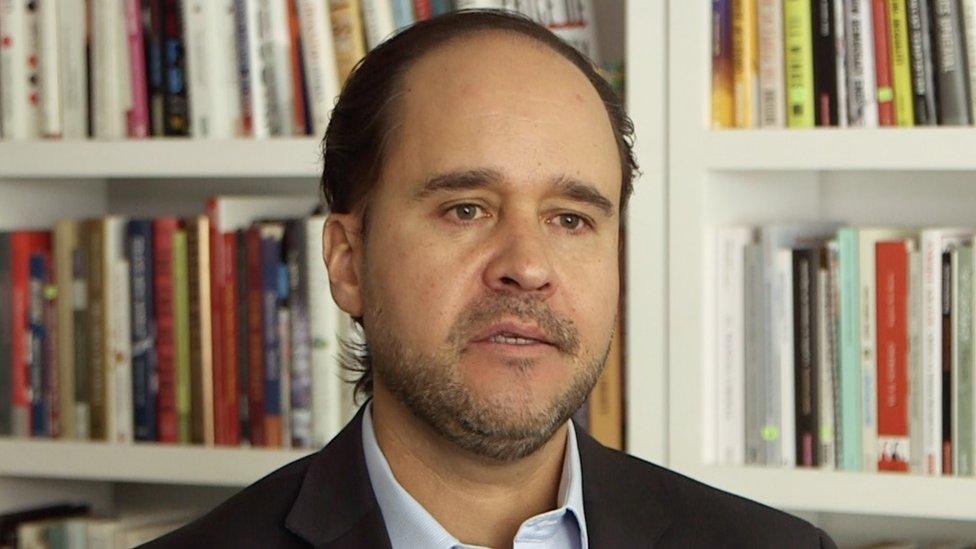

The idea that Mr López Obrador may be trying to find a way to extend his term strikes fear into his opponents. Yet it probably is not the president's intention, says political risk analyst, Carlos Ramírez.

"I don't think so. That would really be a very disruptive event here in Mexico in which re-election has not been allowed since the Revolution in 1910."

Rather, he says, the president wants to "enhance his power during the final part of his administration".

Carlos Ramírez thinks Amlo is not after re-election but does want to strengthen his power

And Amlo and his Morena party may well be playing a longer game by having changed the constitution to introduce recall referendums: "Let's say an opposition candidate wins the 2024 presidential election, then Morena will clearly use this [process of a recall] referendum to try to kick him out."

"It's not a good institutional device, it's not a good idea to have this recall vote every six years," warns Mr Ramírez. "But that's what we have now in Mexico," he says.

As she dips a finger into the mixing bowl to try the masa, the tamal filling, Laura Gómez does not have such qualms about changes to the constitution.

If Amlo were to put re-election on the ballot, she would happily support that too. "For my part, I definitely would. I mean, if he's working well, why would we want change?"

Related topics

- Published7 June 2021

- Published4 May 2021