'Too dehydrated to cry' - a lethal trek for migrants

- Published

Many of the migrants come from Haiti but others come from as far away as Africa and Asia

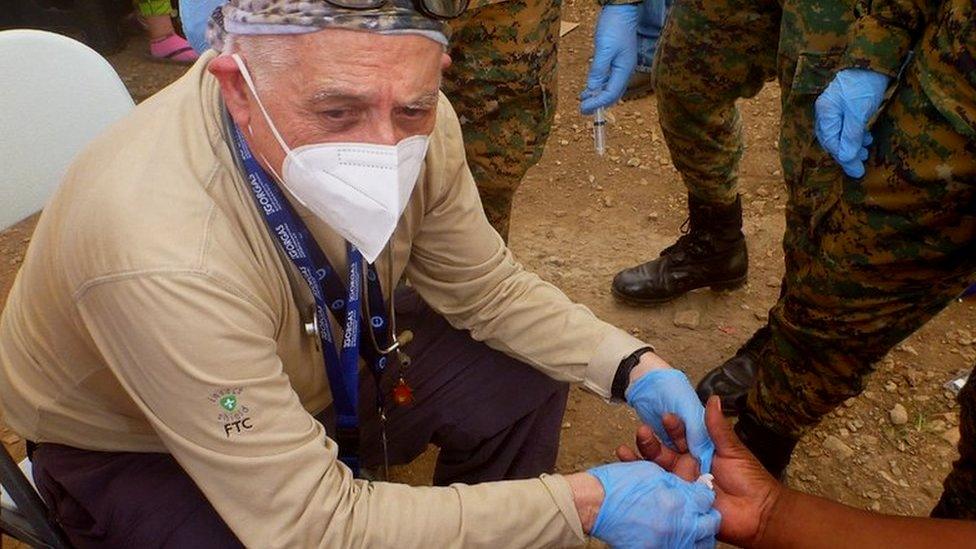

Dr Yesenia Williams was so shocked by what she saw at a migrant reception centre just north of the notorious Darién Gap, she could not talk about it at first - even to her colleagues.

"I did not expect so much suffering and so many difficulties," recalls the paediatrician.

In her nine days at the makeshift clinic in San Vicente, she and her colleagues would treat hundreds of exhausted migrants who had trekked through the dense jungle between Panama and Colombia.

Through their tales, the doctors caught a glimpse of the struggle to survive on what has been described as the most treacherous part of the world's most dangerous migrant route at the end of which, they hope to find sanctuary in the US.

Warning: This article contains descriptions from the beginning which some readers may find upsetting.

It was the plight of the children who made the crossing which moved Dr Williams most.

Some were so dehydrated that their eyes appeared sunken. When they cried, there were no tears, she recalls. Others were so disoriented that they could not remember their own names.

"They have witnessed things they shouldn't have," she says of the violence and attacks some of the migrants suffer during the crossing.

Green hell

The Darién Gap is an expanse of 575,000 hectares (1.42 million acres) of thick rainforest which forms a natural barrier between South and Central America.

There are no paved roads or marked paths to help navigate its lawless expanse, in which robberies and rapes are common.

Despite the dangers, more and more migrants set off on foot on the 97km-trek (60 miles) across swamps and mountains, which can take more than a week to complete.

Of the 133,000 migrants who are estimated to have crossed the Darien Gap last year, 30,000 were children. Many of those embarking on the dangerous crossing are families from Haiti, Cuba and Venezuela but Dr Williams says that she also saw children arriving on their own.

In the nine days that the doctors spent in San Vicente, they treated some 500 of the migrants who made the crossing, 70 of whom they interviewed in depth.

Handing children to strangers

Dr José Antonio Suárez, an infectious disease specialist on the team, recalls tending to a 60-year-old Venezuelan man who was travelling with two children, aged four and five.

There are many Venezuelans among those making the dangerous crossing

Dr Suárez assumed they were the man's grandchildren, but the migrant told him they were not related to him.

The migrant said that the children's mother, a Haitian woman whom he had met in the jungle, had asked him to take them to San Vicente because she no longer had the strength to walk.

"The degree of desperation is such that a parent can hand over a child to a stranger," explains Dr Suárez.

Harrowing accounts of deadly crossing

Dr Roderick Chen-Camaño, a Panamanian epidemiologist with experience working with indigenous communities in the jungle, says he thought he was prepared for what he would encounter at the makeshift clinic.

"I didn't think I would see anything new," he says, before recalling how a Venezuelan migrant burst into tears when he told Dr Chen-Camaño what he had witnessed.

The man said that he had been part of a group of migrants scaling the mountain range which separates Colombia from Panama when a Haitian woman collapsed.

What happened next left the man scarred.

The moment the woman's husband realised she was dead, he threw one of their children over the cliff edge, the migrant said.

The Venezuelan man recalled how he tried to stop the desperate Haitian from doing the same with his other child, but failed.

He also failed to stop the Haitian man from jumping into the void himself, he told Dr Chen-Camaño.

While the BBC has not been able to independently verify the account of the migrant, figures from the International Organization for Migration suggest dozens of migrants die each year crossing the Darién.

Wading through infected waters

Dr Williams says that it is frustrating that all the team could do at the makeshift clinic was the bare minimum, relieving some of the symptoms without dealing with the causes.

"We only see a small part of what the migrants are experiencing," she ponders.

But Dr Suárez, who is from Venezuela, is happy he could at least offer some help to his fellow countrymen.

José Antonio Suárez is happy he can do his bit to help

While most of those braving the Darién Gap last year were Haitians, it has been Venezuelans crossing in 2022.

Many of them left Venezuela in recent years amid their country's economic crisis and tried to eke out a living in other South American countries.

But the strict lockdowns imposed during the Covid pandemic made it even harder for these migrants to get by, meaning that many of them are now heading north in search of new opportunities.

One of the Venezuelan patients Dr Suárez treated at the clinic had an unusual rash on his feet and legs.

Patients were arriving with a rash on their legs

The itchy, red lesions reminded the 67-year-old doctor of something he had not seen since he was a teenager visiting the Unare Lagoon in his native Venezuela.

Dr Suárez diagnosed the migrant, and more than 20 others who arrived shortly afterwards, with cercarial dermatitis, also known as swimmer's itch.

It is caused by parasitic larvae that are released into the water by snails. The tiny larvae burrow into swimmers' skins, causing a rash.

The larvae die but the more a patient scratches the affected area, the worse the rash becomes as the broken skin can easily get infected by bacteria.

But it was one of Dr Suárez's colleagues, paediatrician Rosela Obando, who noticed that while many of the adults had the rash, the children seemed to have avoided infection.

Speaking to the migrants, they found out why.

Parents often carry their children to prevent them from being swept away by the currents

The adults had become infected while wading through the many streams which criss-cross the Darién Gap but the children had been spared because their parents carried them aloft to prevent the currents from sweeping them away.

While the rash rarely leads to complications, it is the drinking of the cercariae-infested water which can have serious consequences, warns Dr Suárez.

But, he explains, the migrants crossing the Darién often face an impossible choice.

Carrying bottled water would weigh them down on their arduous journey, drinking from rivers infested with larvae will cause gastritis, and not drinking will cause dehydration.

'Taken away by the river'

Every one of the doctors has encountered a story which has particularly affected them.

Biologist Yamilka Díaz says she decided to work in the Darién Gap after meeting Delicia. The five-year-old girl was found next to her mother's body in the middle of the jungle.

Delicia was taken to the institute where Dr Díaz worked testing blood samples for tropical diseases such as malaria and dengue.

When Dr Díaz asked Delicia what she remembered about what had happened to her, she just said that her family had been "taken away by the river".

Dr Díaz says that tending to the migrants has changed her life and put more mundane things like the rising cost of living into perspective.

"You see everything differently," says the doctor, who left the makeshift clinic barefoot because she had given her shoes to a migrant whose trainers had become infected with fungus.

- Published23 February 2022

- Published31 January 2022

- Published28 January 2022