Chile: Vote on new constitution but divisions persist

- Published

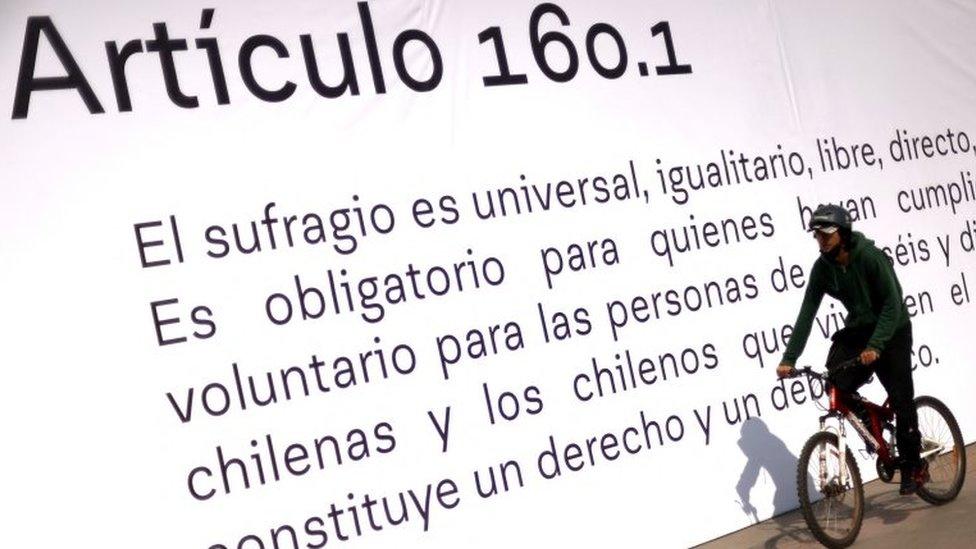

Ahead of the referendum, some of the articles have been printed on banners and exhibited

It was meant to be the final step in a long process aimed at achieving unity in Chile following mass protests. But Sunday's referendum on a new constitution has instead further highlighted deep divisions in the country.

When anti-government demonstrations swept through Chile in 2019, one of the protesters' main demands was for a new constitution to replace the one introduced in 1980 under the military rule of General Augusto Pinochet.

In October 2020, almost 80% of Chileans voted in favour of a new constitution, with many saying they saw it as an opportunity for Chile to become more socially progressive, economically just and inclusive.

When the constitutional convention met for its inaugural ceremony in July 2021, there was a sense of optimism.

But with opinion polls now suggesting that more Chileans are intending to vote against the brand-new constitutional text than to ratify it, that optimism has given way to a sense of uncertainty.

Some even fear that the political and social unrest which swept through Chile in 2019 could return if the constitutional text is voted down.

Lofty aims

The constitution was meant to be a blueprint for a more plural and socially inclusive country.

The draft incorporates demands made by Chile's feminist movement, such as the right to abortion and requiring by law that women hold at least 50% of positions in official institutions.

Celebrations for Chile after constitution vote

It allows for the creation of a state-controlled social security system and declares access to some resources - such as water - a fundamental right.

The new constitution also aims to give indigenous groups more of a voice by declaring Chile a "plurinational" country, recognising its indigenous populations and their right to their lands and resources.

It also establishes the creation of "indigenous autonomous regions" within Chile, although there has been much debate about what this would mean in practice.

Growing concerns

But the referendum comes at a time when a long-simmering conflict between Mapuche indigenous groups and the Chilean state has escalated.

In May, the government imposed a state of emergency in southern areas of the country following the deaths of Mapuche activists, members of the security forces and forestry workers in a series of violent incidents in the last few years.

It comes as little surprise therefore that worries about what some call a "security crisis" have increased.

The proposed de-militarisation of the national police force, the Carabineros - who would shift from being described by law as a "police institution of military character" to a "non-military police of centralised character" - is seen as controversial by many at a time when many Chileans see crime as their number one concern. One poll put that figure as high as 53%.

Opponents of the draft also argue that it is an "irresponsible" document that "attacks" the liberal, free-market political and economic model which they say has made Chile one of the most prosperous nations in the region.

These critics say that the new text will give the state a bigger role in the economy, and that the proposed changes to the political system risk weakening Chile's democracy and institutions.

Dwindling enthusiasm

Support for the draft has declined in recent months with the last poll ahead of the vote suggesting 46% of voters intend to reject the proposed constitution compared with 37% who say they will vote for it.

The number of people who say they will reject the draft has been increasing

Analysts think that the dwindling support is partly to blame on the fact that Chileans have been forced to deal with other more pressing realities, such as the rising cost of living and the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

A wave of fake news about the contents of the proposed text has further eroded support for the blueprint.

Chile's president, Gabriel Boric, says that even if voters reject the draft, Chile will not be stuck with the Pinochet-era document.

Instead, he has suggested a new process would be started to come up with a document acceptable to a majority of Chileans.

Many of the opponents of the current draft back that idea, welcoming the chance to create a text they say would be more moderate and consensual.

In order to allay the fears of those who think the current document too radical, the president has also agreed to allow for "clarifications" so that guarantees to the right to private property can be added and Chile's "indivisible" identity as a nation strengthened.

Related topics

- Published20 December 2021

- Published17 May 2021

- Published26 October 2020