Jair Bolsonaro: The Amazon and why world is watching Brazil's election

- Published

As Brazilians prepare to pick Jair Bolsonaro or Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as their new president, the future of the largest rainforest in the world hangs in the balance.

There is no such thing as silence in the Amazon. The rustle of the trees, the birdsong, the drips of water on leaves after a heavy downpour - the forest is always talking.

But then every so often, it is rudely interrupted; nature's conversation drowned out by the hum of planes or helicopters overhead.

Most of the aircraft belong to illegal gold miners, heading to sites to deliver supplies. The people of Maloca Paapiu hardly bat an eyelid now. And they feel that the authorities are doing the same.

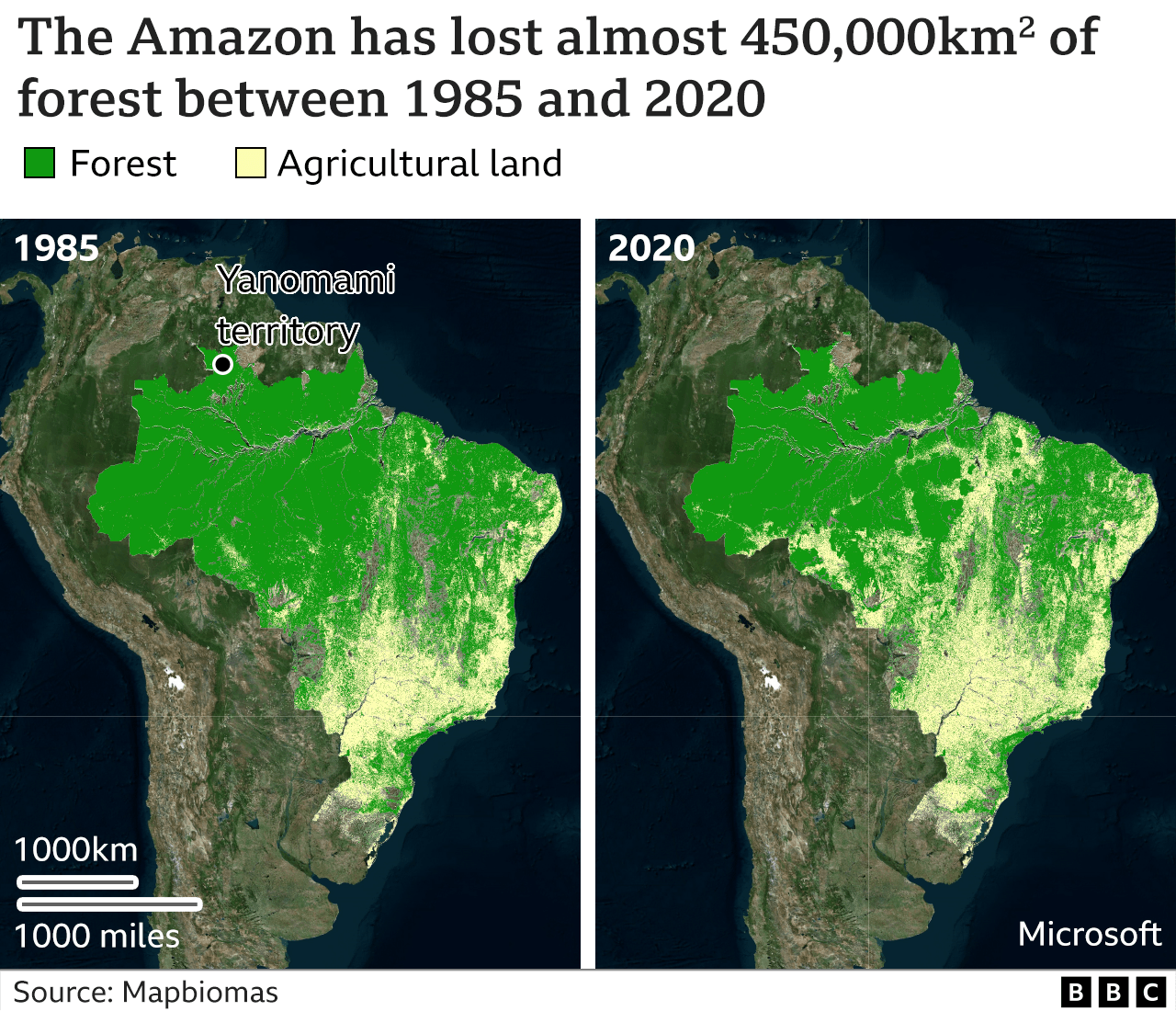

The remoteness of the Yanomami territory is the reason for its beauty - as well as its strife. Close to 30,000 people live a hunter-gatherer lifestyle on a reserve the size of Portugal.

The land is highly coveted - rich in gold and minerals, it has long been in the sights of illegal miners, but in 1992, a presidential decree recognised the Yanomami people's rights to the land.

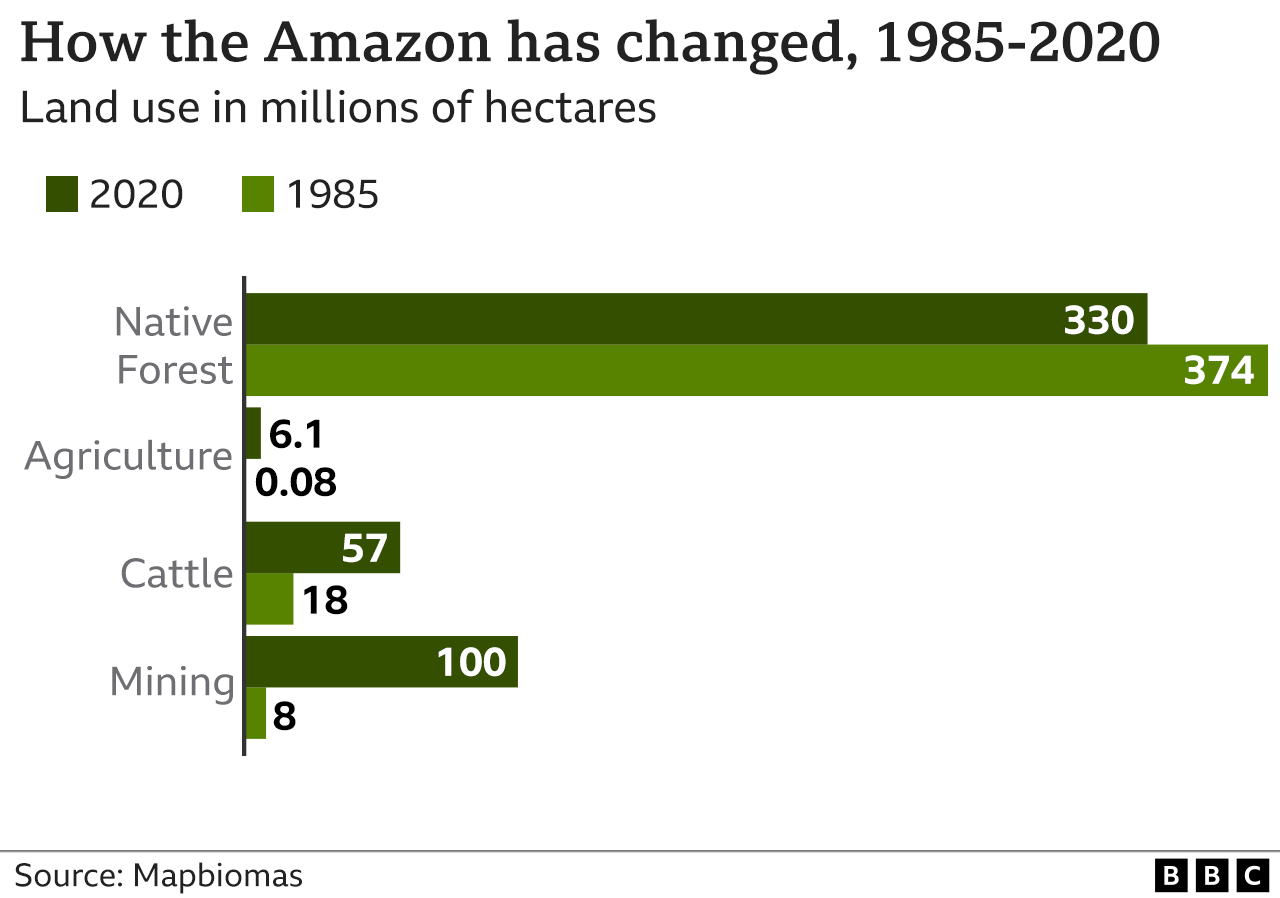

While mining activity decreased after their land was protected, in the past four years under President Jair Bolsonaro, it's hit new highs. The region is experiencing an illegal gold rush.

Bolsonaro wants the rainforest opened up to industry

The small indigenous villages, close to the gold deposits, are the hardest hit.

The health centre in Paapiu has become a sort of front line field hospital. It is a simple wooden hut with intermittent electricity and just a radio to contact the outside world. There's a steady line of people wanting to be seen. Mothers sit on the floor with their babies, bellies distended and their hair discoloured - a clear sign of malnutrition among children.

One woman who appears to be in her 20s comes in looking very weak. She is hooked up to a drip and laid on the only bed in the centre. The health worker explains she too is malnourished and dehydrated.

Outside, there is a makeshift ward for more patients - a simple wooden frame with leaves for a roof and hammocks for beds. Everyone in this shelter has malaria - yet another disease brought in by outsiders and making the Yanomami sick.

"The illegal miners are working near our village, they keep getting closer," Malirina Yanomami tells me. "There's lots of smoke from the machines and that's making kids ill. It causes tummy ache, malnutrition, the kids get skinny. Before, we didn't have so much illness, there were far less serious diseases and we got better quickly."

Malirina's two-month-old grandson has pneumonia. He doesn't have a name - Yanomami parents wait for a few years to name them, out of fear they may die. It's a very real anxiety.

Five minutes walk from the health centre is a creek where three small boys are playing in the water. They have been told not to but like any kids, they ignore their parents. The mercury used to extract the gold from the mine upstream has poisoned these once-crystal clear waters so fishing and drinking here is now impossible.

There are estimated to be around 20,000 illegal miners working in the region, spurred on by the current president. Jair Bolsonaro maintains that the Amazon is rich in resources and local people need to be able to benefit from that. So he has proposed a law that would legalise mining on indigenous areas.

At the same time, locals complain that surveillance of practices detrimental to the Amazon has fallen.

"Most organised crime associated with deforestation - forest degradation, illegal mining - is easy [to identify] because the satellites pick up the first day of deforestation," says renowned scientist Carlos Nobre.

He is referring to a system introduced in Brazil in 2004 - DETER - which helps government agencies combat crime in the forest, giving daily data on deforestation.

"Unfortunately, the political discourse of the current president of Brazil has always been, 'go ahead, deforest, do some gold mining, do whatever you want. The forests have no value."

The gold mines are actually easy to spot. In a sea of unbroken green, the forest suddenly opens up. The land scarred by excavators and pools of water, sifted by miners searching for treasure.

Miners are often armed - in this criminal world, it's hard to know who to trust.

"It's like any city, there are good and bad people," says 24-year-old Danilo - not his real name - who has worked in illegal mining for a few years now. "When it comes to gold, you have to protect yourself."

Danilo prefers to trade everyday goods. A 2 litre bottle of Coca-cola sells for 8 reais in the city ($1.50). In a gold mine, it sells for closer to $50.

This thirst for gold means the way of life for the Yanomami hangs in the balance. And the current government seems unwilling to stop the miners.

"If Bolsonaro wins again, he'll kill us all," says shaman and leader Davi Kopenawa Yanomami. "We are surrounded by big politicians who don't want to know us or respect us."

Davi Kopenawa Yanomami

With large amounts of money being earned on Yanomami land, some of the indigenous community have become part of the industry - whether through being paid to grant access to the miners or mining themselves.

"A minority of young Yanomami are involved," admits Davi. "They think illegal mining helps - but it doesn't, it just kills people."

As you fly over the vast pristine forest - the only viable way to get to many of the villages - golden rivers break up the canopy, weaving through the trees. Up close, some are vast - and fast-flowing. It's on these waterways that the miners travel on motorised canoes.

A 53-year-old mother of six, Maria is building a new house in the state capital, Boa Vista. She's replacing a wooden shack with a brick structure together with glass windows and tiled floors. All this paid for by her work as a cook at the mines.

She started working when she was 22. Employed as a domestic worker by a pilot at the illegal mines, he offered her her first job.

"I worked there for three-and-a-half months, and came back and was able to buy my first wooden house," says Maria, which is not her real name.

Maria risks her life to cook for the miners

In the corner of her bedroom are a couple of plastic jerrycans. Inside, she's packed clothes, a piece of rope for a hammock and some bug spray to ward off the malaria-infested mosquitos.

She's ready for the phone call that's bound to come soon, one of the mine owners she knows asking her to travel back to the forest. It doesn't mean she's not terrified. A few months ago, her canoe capsized and she only managed to stay afloat thanks to the jerrycan.

"I'd prefer us to go without than have my children do this too," she says. "Because it's illegal, you run the risk of being arrested. But my son doesn't have work and he has a family."

With debts to pay, Maria doesn't believe they have an alternative. Maria, though, is rare in the mining community in the fact that she doesn't want Bolsonaro to win a second term.

"He campaigned in 2018 saying he would legalise mining - and when he does that, he's incentivising everyone to do it," she says. "As president I think he has to make the Brazilian economy better so people have more job opportunities away from illegal mining."

The police station's car park in Boa Vista is testament to the booming mining industry. Dozens of planes and helicopters confiscated from suspected illegal miners - some of them even prominent local businessmen.

Mining is most definitely in this region's blood. In front of the governor's palace stands a monument dedicated to the prospectors of the past. The current governor - an ally of Bolsonaro's - wants that tradition to continue.

"We have the right to exploit our natural wealth, benefitting indigenous communities," Antonio Denarium explains.

"The way it is today, all the mining that takes place in Roraima leaves the state illegally, not paying any taxes, no fees that will compensate the environmental damage caused by the mining. In the Brazilian Amazon there are 23 million people and those people need to work."

When I ask miner Danilo about the future of the rainforest, it's of little consequence.

"I just want to live for today," he admits. "Life is short." But he does agree he's causing damage.

"When the excavators start to work, they create a massive hole. And you can't fill it in," he says.

As for the impact on the indigenous communities, he has little sympathy.

"They're more shameless than the miners," he says. "Every journey to the mines, you pass through an indigenous area. If you don't pay them off, they won't let you through. I used to have this vision of mining being bad for the indigenous, deforestation being damaging. But I saw they were part of the problem."

The Amazon matters to the world, absorbing huge amounts of greenhouse gases but for those living in the rainforest, getting by is what they care most about.

What will resolve the problem of poverty in the Amazon is creating new alternatives for the economy, says Marina Silva, Lula's former environment minister. "But we can't continue to destroy the forest because otherwise it will go past the point of no return."

She left Lula's government in 2008 after disagreements over his infrastructure projects in the Amazon. Does she really see him as the Amazon's saviour?

"I think Lula today has a wider understanding of what's at play in relation to climate change and the role the Amazon has."

"It's not the job of one person, this idea of a saviour doesn't apply to the reality of the world we are living in, with all its complexities. But I do believe he can contribute greatly."

How will the Yanomami community - and the Amazon - look in a few decades from now?

There's no doubt, competing forces in the Amazon are changing how they live their lives.

In this vast rainforest though, there's little hope that politicians can keep them safe.

Photos by Katy Watson

.