Brazil's far-right faithfuls are not giving up

- Published

Protesters opposed to Lula's election have been camped out outside the barracks

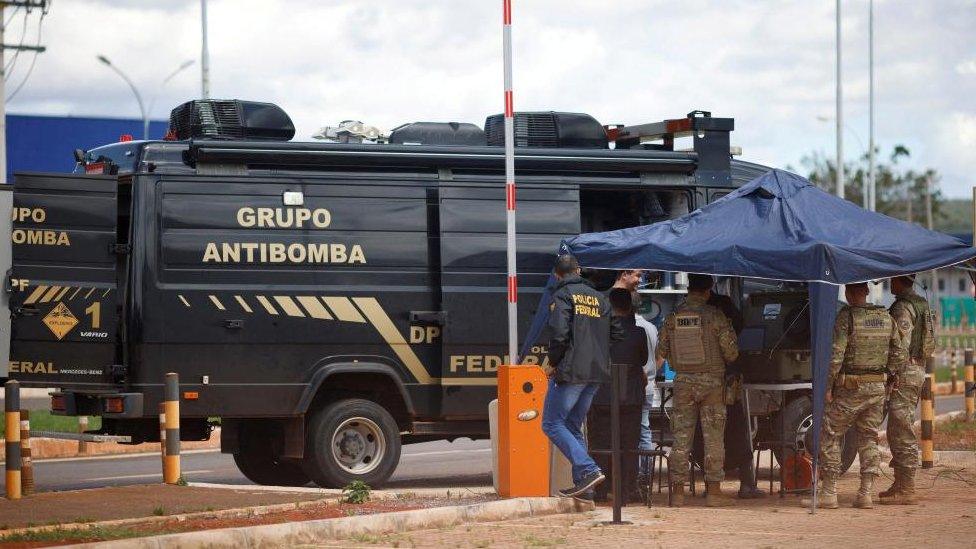

Following the arrest in Brasilia of a supporter of outgoing President Jair Bolsonaro for allegedly trying to set off a bomb to create chaos ahead of the inauguration of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva as Brazil's new president, the BBC's South America correspondent Katy Watson examines the risks that hardcore Lula opponents pose for his presidency.

Outside the military barracks in the centre of São Paulo, there is a small group of about 50 people protesting.

Draped in Brazil's flag, they are chanting: "Armed forces, save Brazil." Some are waving banners with the words: "Our flag will never be red - out with communism".

Around them, dozens of tarpaulin tents have been set up, most of them green, blue and yellow, the colours of the national flag, which are now associated with the country's far-right.

One young man who introduces himself as Rodrigo is camping out in one of them, along with four other people.

Rodrigo says he is willing to stay outside the barracks long-term if need be

He pitched up just after October's presidential election in which the far-right candidate he was backing - incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro - narrowly lost to left-winger Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

"It's a greater cause," he says, explaining that he is here to stay and not considering returning home.

When asked whether Jair Bolsonaro is the driving force behind his decision to stay on and protest, he admits he is.

"He's influential on social networks - the things he posts about family, God, liberty, which are our principles, make us stay here."

But fellow protester Luca Oliveira disagrees - he says their movement is bigger than the soon-to-be former leader.

"Our voting system? It's a fraud," says Luca. He claims Brazil's electronic voting system is prone to irregularities and that the "biased" Supreme Court is doing nothing about it.

It is a familiar argument. Jair Bolsonaro made it throughout the election campaign, providing no proof to back it up. But repeat the allegations over and over again, and that is enough to keep this group of people on the streets.

"We are calling for something different," Luca says, without defining exactly what that is.

The truth is, people here want the military to get involved.

"I come here mainly because we have reason to believe that the elections were not done in a clean manner," explains 22-year-old Sofia, a law student who did not want to give her surname.

Sofia is a law student who thinks the army should intervene

"Lula da Silva is an ex-convict. Having him become president is basically saying it's OK for you to be a criminal here in Brazil," she says referring to the time the president-elect served in jail before his conviction was annulled.

Sofia argues that under Brazil's constitution, it falls to the army to intervene to take care of national security in cases when there is something wrong with the elections or the electronic voting machines.

She says that the armed forces should take "whatever measures necessary" to ensure "the election is correct".

But there is no sign that Brazil's military wants to intervene.

A report by the armed forces on the security of Brazil's electronic voting system found no evidence of fraud during the elections, although it did point out some vulnerabilities that it said could be exploited.

That sliver of doubt is enough to keep these protesters hoping for a radical U-turn from the authorities.

It is a scene replicated across Brazil since Lula won the presidential elections at the end of October.

One demonstrator is carrying a sign which reads "#Brazilianspring" in a reference to the mass protests in 2013, when more than a million people took part in anti-government protests in about 100 cities across the country.

The demonstrators believe the election was "stolen" by Lula

Political scientist Jonas Medeiros says these protests are nothing like on the scale of the unrest the country experienced back then.

But he does caution that what is happening now is worth paying attention to. "There is a tendency in the progressive camp as well as the media to minimise their [the protests'] importance," says Mr Medeiros.

"That they are just a minority of interventionist pariahs, so don't give them any attention. But these people are building networks, possible civil organisations and this is the seed for the future of the opposition that Lula will have to deal with for the next four years."

Michele Prado is also a political scientist. She knows first-hand how these protesters operate, because until recently she was one of them.

She voted for Jair Bolsonaro in 2018 and talks about having become "radicalised" before she realised that many of arguments she had read on right-wing WhatsApp groups "weren't democratic".

She says she fell for the narrative which "appeared to defend democracy and liberty".

But even though Ms Prado may have had a change of heart, she insists Mr Bolsonaro's influence remains strong.

"Just look at his behaviour until now. He's still not given a declaration [after Lula's victory]," she says referring to the fact that the outgoing president has not admitted defeat.

Jair Bolsonaro has not been seen in public much since he lost in the election

"He left the door open for extremist mobilisation to continue. He legitimises this radicalisation and the extreme right because he himself spent his entire mandate attacking democratic institutions, disrespecting minorities, the separation of power," she explains.

Law student Sofia is one of those still holding out for the armed forces to somehow prevent the handover of power from happening.

She says she believes "the armed forces will actually do something" to stop Lula from taking office.

It is an unlikely outcome that those protesting alongside her outside the army barracks may still be holding out for, but one that few Brazilians truly believe will occur.

Related topics

- Published26 December 2022

- Published13 December 2022

- Published24 November 2022

- Published1 November 2022