Coming face to face with inmates in El Salvador's mega-jail

- Published

In the cells, the prisoners sleep in bunk beds with four tiers

Hundreds of eyes are upon us. With shaven heads, dressed in pristine white, and heavily tattooed, the prisoners know they are being watched and return the gaze from the other side of the bars.

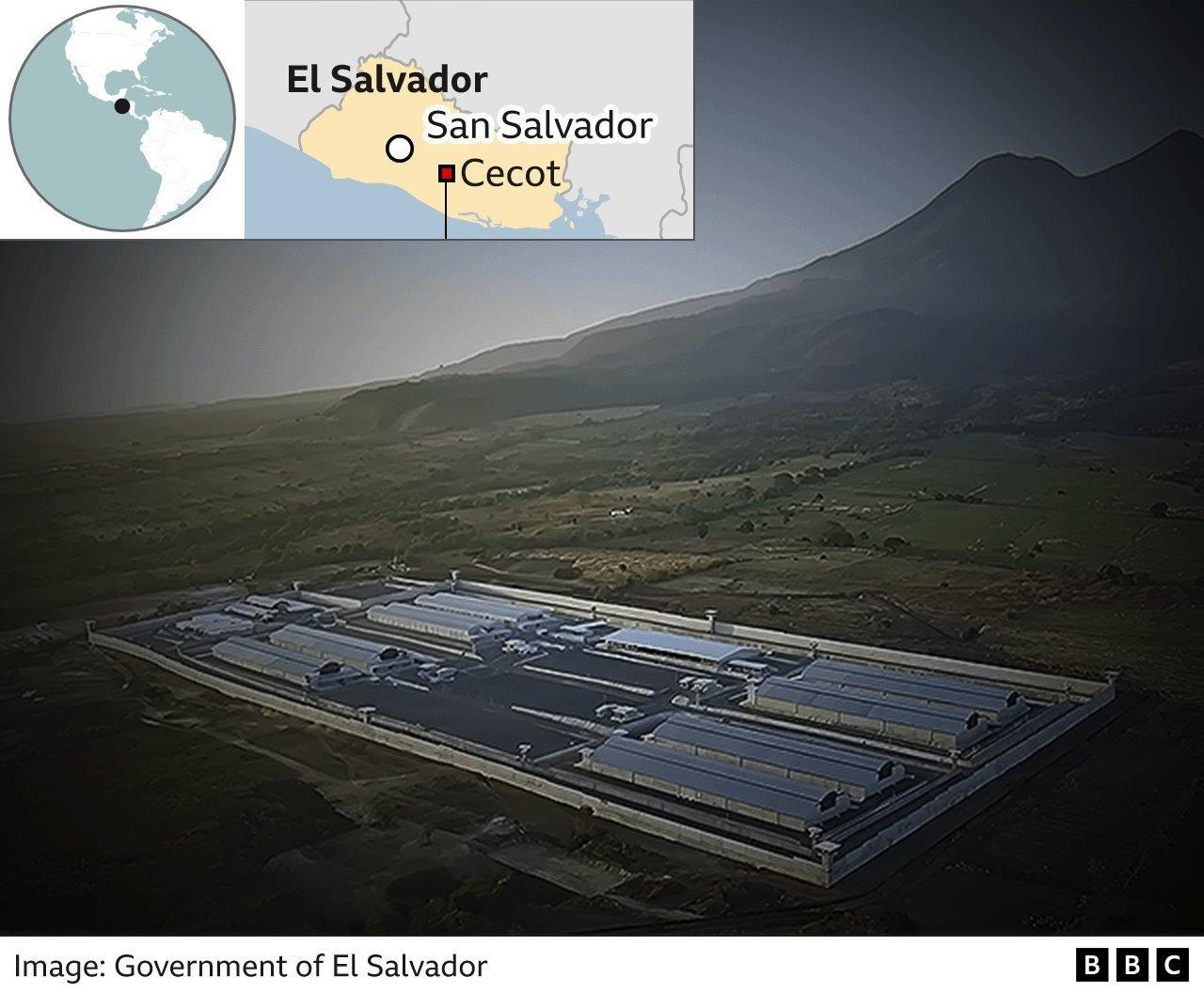

We are in Cecot (Centre for the Confinement of Terrorism), a maximum security jail built a year ago by the Salvadoran government to imprison "high-ranking" members of the country's main gangs.

A gargantuan complex constructed in the middle of nowhere, it symbolises President Nayib Bukele's controversial security policy more than any other project.

Critics of the president have called it a "black hole of human rights", where international guidelines on prisoner rights are flouted.

Miguel Sarre, a former member of the United Nations Subcommittee for the Prevention of Torture, has described it as a "concrete and steel pit".

And referring to the fact that no-one has so far been released from the jail, Mr Sarre warned Cecot appeared to be used "to dispose of people without formally applying the death penalty".

But in a nation where notorious gangs such as Mara Salvatrucha and the two factions of Barrio 18 - the Revolucionarios and the Sureños - have wreaked deadly havoc, the jail has been a major reason behind President Bukele's huge popularity and his success in the polls.

"Here are the psychopaths, the terrorists, the murderers who had our country in mourning," announces the director of the centre during a carefully choreographed tour of the cells organised by the government for international media.

"Don't look them in the eyes," the director, who does not want to be named but allows himself to be filmed, warns us.

The director of Cecot was the tour guide for foreign journalists

It is the middle of the night, but in here, the artificial lights are never turned off.

A waft of air filters through the lattice ceiling, providing a brief respite from the heat. The temperature in the cells can reach 35C during the day and there is no other source of ventilation.

The prison may have been called "the Alcatraz of Central America" but it is not run down - everything is new, smooth, recently painted.

Hooded guards keep watch from above, gun in hand.

Below, the prisoners climb onto the four-storey bunks on which they sleep. Without any mattresses or sheets, they have to lie on bare metal.

They eat the food they are given - rice, beans, hard-boiled eggs or pasta - with their hands.

"Any utensil can be [fashioned into] a deadly weapon," the director explains.

Watch: Rare video shows El Salvador inmates in their cells in mega-jail

There is nothing else within the cell's three cement walls apart from two sinks for prisoners to wash in and two toilets, which inmates have to use in plain sight of everyone else.

And there is nothing else to do but watch time go by.

Inmates only get to leave these cells for 30 minutes a day to exercise - using only their own bodyweight - in the central corridor of Block 3, which is the one our group of journalists is allowed to inspect.

There are seven other blocks like this one within the enormous complex, which covers the equivalent of seven football stadiums.

The compound is surrounded by two electrified fences and two reinforced concrete walls, and guarded by 19 towers.

Cecot is located in Tecoluca, 74km (46 miles) south-east of the capital, San Salvador

According to the government, Cecot can hold up to 40,000 inmates.

But it is not clear how many are currently locked up there. Nor on what grounds those who are there have been selected for this facility.

Asked directly about the number of prisoners, the director responds: "We can't provide that information."

"What is the maximum capacity of each cell?" we insist.

"Where you can fit 10 people, you can fit 20," the director says, appearing to smile from behind his anti-Covid mask.

The BBC and other media gained access to Cecot during a carefully managed guided tour

Since the jail opened on 31 January 2023, the BBC had repeatedly requested access to the mega-prison.

It was finally granted two days after President Nayib Bukele claimed victory in the presidential election held on 4 February with more than 80% of the votes.

In his victory speech - delivered from the balcony of the presidential palace to cheering crowds - Mr Bukele congratulated himself for having turned El Salvador, which was once the murder capital of the world, into one of the safest countries in the region.

President Bukele spoke to his supporters from the balcony of the National Palace on the day of the election

He also attacked those who have accused his government of human rights abuses.

Allowing international journalists to tour the prison which has become emblematic of his "iron fist" security policies appeared to be another attempt to sway those who doubt him.

After all, there has been no shortage of criticism from human rights groups.

El Salvador now has the highest incarceration rate in the world.

More than 70,000 people have been detained under the "state of exception", an emergency measure granting draconian powers to the police and military that has been in force for two years.

Local and international human rights groups warn that thousands of those detained under the state of exception have no discernible links to gang crime.

Others were forced to collaborate with the gangs - they acted as lookouts or hid guns or drugs for them out of fear for their lives, rights group point out.

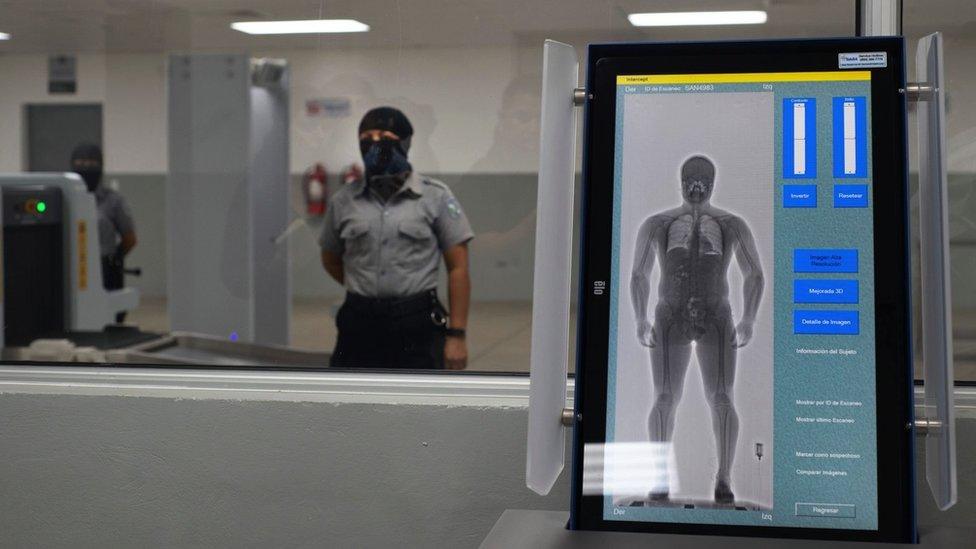

Security measures in the prison include an x-ray machine to detect hidden items that shows even internal organs

The conditions within prisons have also come under criticism.

Cristosal, the primary human rights organisation in the Central American country, has documented torture cases and more than 150 deaths in state custody since the government declared a "state of exception" in 2022.

Amnesty International (AI) warns El Salvador is experiencing the "gradual replacement of gang violence with state violence".

In a report published in December, external, AI accused the Salvadoran authorities of adopting "a systematic policy of torture towards all those detained under the state of emergency on suspicion of being gang members".

"Among the gravest consequences are deaths in state custody," it says. But Amnesty says that "many others are the result of inhumane conditions of imprisonment or denial of medical care and medicine".

The prison director says that no external institutions or NGOs are allowed to visit the prison.

He insists that it complies with international standards, but we have no way to check this for ourselves nor do we have access to any parts of the jail not shown to us as part of the tour.

The government argues that it is dealing with hardened criminals guilty of heinous crimes and gruesome violence.

On our tour of the prison, we are brought face to face with five prisoners selected to drive home this point.

This inmate's tattoos indicate that he is a member of the Mara Salvatrucha gang

With their arms and legs shackled, they are led from their cells and made to crouch facing the wall.

They are not allowed to talk.

"Come here. Turn around, please. Take off your shirt," a guard orders the first inmate.

We are told the prisoner is a "hitman for the Mara Salvatrucha" who was sentenced to 269 years in prison for kidnapping, torturing and murdering - along with other gang members - four soldiers.

A man convicted of the femicide of a 16-year-old schoolgirl also has to show us his torso bearing the tattoos which are typical for gang members.

One of the Salvadoran photographers who is part of our group later tells me that the girl was held captive and brutally murdered, her body dumped in a canal.

Prisoners at Cecot spend all but 30 minutes of their day inside their cells

Salvadorans are not strangers to brutal crimes like those the inmates are serving time for.

In the days leading up to the election, people in street markets, on beaches, in city hotels and in poor neighbourhoods told me about the influence gangs had wielded before the government cracked down on them.

"Every month a boy used to come to charge us," María de la Luz Paniagua, who owns a grocery store in Santa Ana, said of the frequent extortion demands.

"If you didn't pay, they threatened you with a knife."

Others recalled not being able to move freely because whole neighbourhoods were under gang control.

Many spoke out in support of the state of emergency imposed by President Bukele.

"Since it is in place, there are no gang members and we really feel relieved," María says.

"There are always little things that don't work," she concedes, saying that some people have been unjustly detained.

But for her, it is a price worth paying.

"Before, we lived in fear. Not anymore."