Fears of split in Israeli-Lebanon border village

- Published

Israeli and Lebanese soldiers were killed in a gunfight a short distance from here earlier this year

Depending on whose version of history you believe, the village of Ghajar could be in Syria, Lebanon or Israel.

The United Nation's so-called blue line between Israel and Lebanon runs right through the middle of the village, but for several years Israel has occupied Ghajar.

The Israeli government is now finalising plans to pull out its troops from the Lebanese part of the village, but the move could create as many problems as it solves.

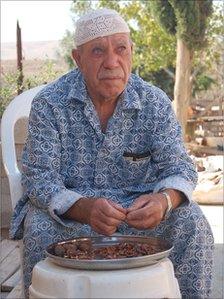

Cracking nuts outside the home he's lived in for most of his life, Hassan Khamouz was born a Syrian.

Some residents of Ghajar are unsure about what the future will bring

In his forties, after the annexation of the Golan Heights, he became an Israeli citizen. Now, towards the end of his life, he's about to become Lebanese.

"I'm just an Arab member of the village. The (village) committee will tell us what to do - I don't really know what's happening," the old man told me as he, perhaps understandably, leaves this complicated issue in the hands of others.

Mr Khamouz and some 2,000 other people live in this picturesque hillside village on the front line between Israel and Lebanon.

When Israel's military occupation of southern Lebanon ended in 2000 Israeli troops remained in Ghajar, even though UN mappers determined that the northern part of the village was actually in Lebanon.

Clearly defining the Blue Line - the unofficial border - is a priority for the UN.

Israel and Lebanon are still technically at war and earlier this year, just a few miles from Ghajar, Israeli and Lebanese soldiers were killed in a gunfight over removing trees along the blue line.

Divided families

Now the Israeli government is discussing proposals to pull out of northern Ghajar, fulfilling its obligations to the UN but, in so doing, creating another problem a village cut in two.

Many services, like the school and municipal buildings, are in the southern, Israeli part of Ghajar.

Families are spread out on either side of the village, and people like Najib al-Khatib, a community spokesman, are worried.

"People in the north have brothers in the south. It's like one big family and I can't leave my relatives in the north behind," says Mr Khatib.

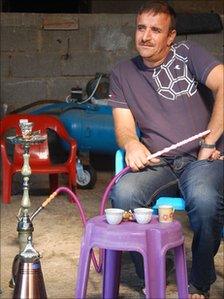

A minority of villagers are unconcerned about the changes

Speaking in fluent Hebrew, he, like most villagers is from the minority Arab Alawite sect but holds an Israeli identity card and is anxious about what might happen if part of the village comes under Lebanese control.

Others, like Mohammad Fatali, are more phlegmatic. His house is only a few hundred metres inside the northern part of Ghajar and has no intention of moving his family or his job when Israeli troops withdraw.

"Even though I have an Israeli ID card, I think things will be OK if Israel leaves. Things might improve under Lebanese rule," said the 46 year old - whose apparent lack of concern isn't typical of most villagers.

UN troops should initially fill the vacuum in northern Ghajar when Israel withdraws.

But with an international frontier running through the middle of the village, Israel could soon be facing its enemies from Hezbollah and the regular Lebanese army on the other side of Main Street.

- Published17 November 2010

- Published4 August 2010

- Published3 August 2010