Egypt shark attacks: Red Sea resorts seek explanation

- Published

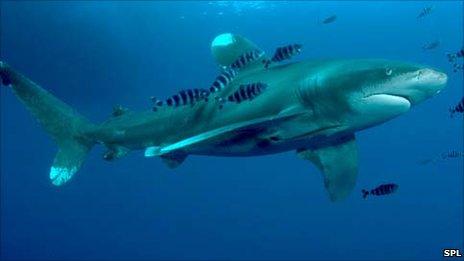

White tip sharks frequent the Red Sea area

International shark experts are arriving in Egypt to help investigate the attacks off the Red Sea resort of Sharm el-Sheikh that have baffled local officials.

Scientists agree that such attacks are extremely rare - and that sharks are not the man-eaters depicted in Hollywood blockbusters such as Jaws.

But they will try to determine why the sharks were lured into shallow waters, and what prompted them to carry out a series of attacks that left one person dead and several more injured.

So far, two sharks - an oceanic white tip and a mako shark - have been caught by local fishermen, but experts say there is no evidence so far that either of them are responsible for the attacks.

There is an abundance of oceanic white tip sharks - Carcharhinus longimanus - in the Red Sea. Divers have spoken of diving with oceanic white tips without feeling threatened.

But Ian Fergusson, a shark biologist and patron of the Shark Trust, a UK conservation organisation, said the presence of the short-fin mako shark was intriguing.

Oceanic white tips frequent the region but it was unusual for swimmers to encounter them in shallow waters, he said, and it was very rare for shortfin makos to be found in the Red Sea - and exceptionally rare to find them close to shore.

He said the last time a short-fin mako attacked in the area was in 1970s, when a tourist was wounded in an attack off Eilat's reefs.

Mr Fergusson, a regular visitor to the area, said it would not be difficult for a shark to get close to the shore in Sharm el-Sheikh.

"That particular part of the coastline is bordering on deep water. You don't have to go far offshore to find yourself in 500 metres of water. Sharks can get within half a mile of the shore easily. They don't, for example, have to cross reefs to get there."

World War II attacks

According to the University of Florida's International Shark Attack Files, external, there are an estimated 70-100 shark attacks on humans per year, resulting in about five to 15 deaths. Of those, the oceanic white tip is responsible for only a small number.

But the large oceanic sharks were also the main culprits behind countless attacks on sailors and airmen who, after air and sea battles, found themselves adrift in the Pacific during World War II.

So what could have prompted the latest attacks?

There has been speculation that animal carcasses were recently dumped into the Red Sea, not far off the shore. Some reports have suggested the remains could have been thrown overboard by a ship carrying animal cargo.

"If you start dumping carcasses, you couldn't ask for a better way of baiting for sharks," said Mr Fergusson.

David Jacoby, who specialises in shark behavioural ecology at The Marine Biological Association of the UK, agreed that if this is the case, it was likely to be a significant factor in the sharks' behaviour.

"Pelagic, or oceanic, species of shark often feed opportunistically because the open ocean can be a sparse environment for food," he said.

Opportunistic?

While less is known about the movements and behaviour of the oceanic white tip, compared with some other species, Mr Jacoby offered another possible explanation as to why the sharks might have been in shallow water.

Based on evidence, experts know that in other shark species, larger females move into warmer, shallow waters to either aid gestation - which can be between 9-12 months in white tips depending on the temperature - or to pup, although from what little evidence there is, it seems that oceanic white tips probably pup in the early summer.

"Both species [white tips and makos] rarely encounter people as they spend large amounts of their time in blue water - open ocean," said Mr Jacoby.

"Like other species, the oceanic white tip is opportunistic and can be fairly aggressive. It is hard to speculate why they attack but they might if they felt they were threatened.

"They are not coming specifically to attack humans - they are not seen as a food source. But if a white tip or mako felt threatened, felt cornered by lots of people in the water, or next to a reef, for example, it might display more aggressive behaviour as a defence mechanism.

"They are opportunistic and it could just be a case of people being in the wrong place at the wrong time."

Or, he said, they could be cases of mistaken identity - the shark misinterpreting a human for its normal prey.

Mr Jacoby said shiny objects in the water could attract attention from sharks - so if the sharks were already in the area, shiny jewellery might be a trigger.

There has also been speculation that sharks could have have moved to shallow water because of the depletion of local food sources in the area, but Mr Jacoby disagrees with this.

"This would surely have the opposite effect," he said.

He explains that sharks adopt search behaviour aiming to maximise their encounters with food sources. Therefore, there is likely to be a relationship between natural prey distributions - fish, squid etc - and shark distributions, as the sharks generally try and go where the food is.

The last recorded death from a shark attack in Egypt was in June 2009

However, if a potential food source such as carcasses have been discarded close to shore, some sharks would naturally pick up on this and opportunistically feed there. This would increase the numbers of sharks in the area, making interactions with people more likely.

'Chumming'

In the past, shark attacks on snorkellers have been blamed on shoddy diving practices such as "chumming" - attracting sharks by throwing solid bait or pouring chum, a mash of fish oil and blood, into the water.

This type of activity aims to attract sharks such as oceanic white tips, which tend to stay out in the ocean.

But Mr Fergusson said he didn't "buy" this theory.

"Recent studies in South Africa have shown that chumming has limited effect on shark behaviour.

"This is partly because these sharks are such migratory species, and mainly because this is a Marine National Park, any feeding is prohibited - anyone found doing it would be arrested and jailed."

He said a more compelling argument could be a continued decline in pelagic fish stocks having an impact on the natural foraging behaviour of certain shark species.

While any degradation to the ecosystem of the local reef wouldn't necessarily affect the oceanic white tip because this is outside of its natural habitat, Mr Fergusson said this could "point to a larger issue of general offshore fishing of tuna and other big fish whittling down and influencing the food chain".

In Egypt, the hunt is still on for the shark that carried out the latest, fatal attack.

Mark Murphy, who runs a scuba diving holiday firm in London, told the BBC that the local authorities would probably aim to have a "quick clean-up of the area".

"There are over four million visitors a year to the Red Sea and there hasn't been a single incident within the last five years," said Mr Murphy.

"I am saddened that the Egyptian government has decided to slaughter sharks indiscriminately. Over 70 million sharks a year are killed by humans and they are an essential part of the marine ecosystem."

In any case, according to US-based shark expert Samuel Gruber, finding the predator or predators would be extremely difficult.