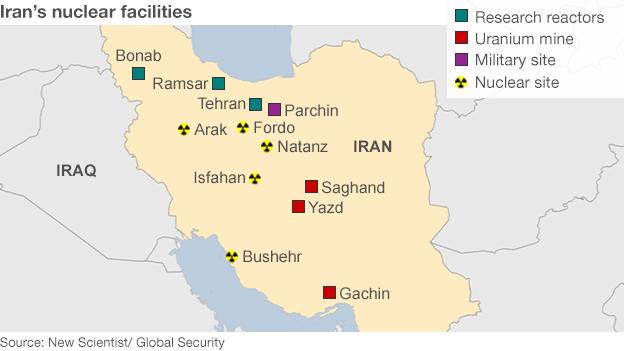

Iran's key nuclear sites

- Published

Iran has agreed with six world powers to limit its sensitive nuclear activities for more than a decade in return for the lifting of sanctions. The country has a number of nuclear sites, which are monitored by the global watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

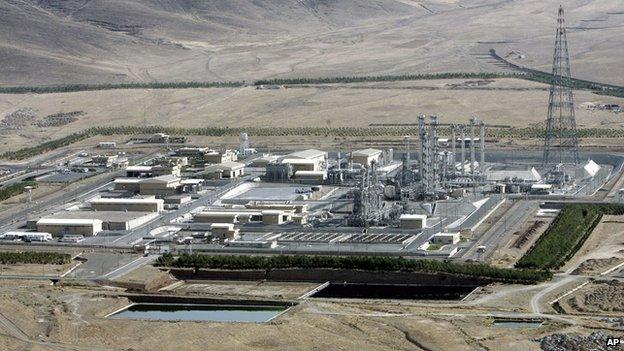

Arak - Heavy water reactor and production plant

The existence of a heavy-water facility near the town of Arak first emerged with the publication of satellite images by the US-based Institute for Science and International Security in December 2002. Spent fuel from a heavy-water reactor contains plutonium suitable for a nuclear bomb.

In August 2011, the IAEA visited the IR-40 heavy-water reactor site at Arak. Iran told the IAEA the operation of the reactor was planned to start by early 2014.

World powers had originally wanted Arak dismantled because of the proliferation risk. As part of the interim nuclear deal signed in November 2013, Iran agreed not to commission or fuel the reactor.

Under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), external agreed on in July 2015, Iran will redesign the reactor so it cannot produce any weapons-grade plutonium and presents less of a proliferation threat. All spent fuel will be sent out of the country as long as the reactor exists.

Iran will also not be permitted to build additional heavy-water reactors or accumulate heavy water for 15 years.

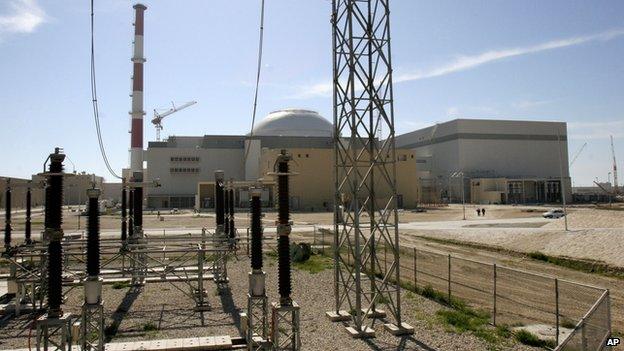

Bushehr - Nuclear power station

Iran's nuclear programme began in 1974 with plans to build two commercial nuclear reactors at Bushehr with German assistance.

The project was abandoned because of the Islamic revolution five years later, but revived in the 1990s when Tehran signed an agreement with Russia to resume work at the site.

Moscow delayed completion of the project while the UN Security Council debated and then passed resolutions aimed at stopping uranium enrichment in Iran. While enriched uranium is used as fuel for nuclear reactors, it can also be used to make nuclear bombs.

In December 2007, Moscow started delivering the canisters of enriched uranium the plant needed and it was officially linked up to Iran's national power grid in September 2011, generating 700MW of electricity.

In August 2013, an IAEA inspection of the plant indicated that the reactor was operating at 100% of its nominal power.

The reactor has raised safety concerns due to the merging of a German and Russian design. It is also close to a major fault line and the region frequently experiences earthquakes. In April 2013, there was a 6.3-magnitude earthquake in the area.

Gachin - Uranium mine

In December 2010, Iran said it had delivered its first domestically produced uranium ore concentrate, or yellowcake, to a plant that could make it ready for enrichment.

The IAEA says evidence suggests the Gachin mine, near the Gulf port of Bandar Abbas, was originally intended as a source of uranium for a military nuclear programme. It does not produce enough yellowcake to refuel an electric power reactor - but a nuclear weapons programme uses far less.

Iran was believed to be running low on its stock of yellowcake, originally imported from South Africa in the 1970s. But since Gachin, it has opened two further uranium mines at Saghand in central Iran and a yellowcake production factory at Ardakan.

In January 2014, IAEA inspectors were allowed to visit the Gachin mine for the first time since 2005.

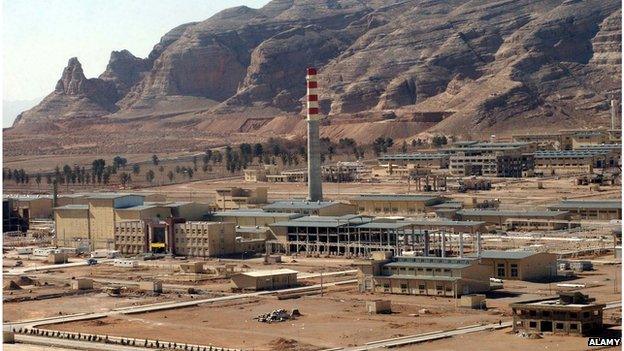

Isfahan - Uranium conversion plant

In 2006, Iran began operating a uranium conversion facility (UCF) at its nuclear research facility in Isfahan to convert yellowcake, external into three forms:

Hexafluoride gas - used for enrichment processes

Uranium oxide - used to fuel reactors

Metal - used in some types of fuel elements, as well as the cores of nuclear bombs

IAEA inspectors were allowed to visit the site in November 2013.

Natanz - Uranium enrichment plant

The Natanz fuel enrichment plant (FEP) is Iran's largest gas centrifuge uranium enrichment facility. It began operating since February 2007, in contravention of UN Security Council resolutions demanding Iran halt uranium enrichment.

The facility consists of three large underground buildings, capable of holding up to 50,000 centrifuges. Uranium hexafluoride gas is fed into centrifuges, which separate out the most fissile uranium isotope U-235.

The FEP produces low-enriched uranium, which has a 3%-4% concentration of U-235. That can be used to produce fuel for nuclear power plants, but also be enriched to the much higher level of 90% needed to produce nuclear weapons.

Under the July 2015 JCPOA, Iran has agreed to install no more than 5,060 of its oldest and least efficient centrifuges at Natanz for 10 years. Uranium enrichment research and development activities will take place only at Natanz and be limited for eight years.

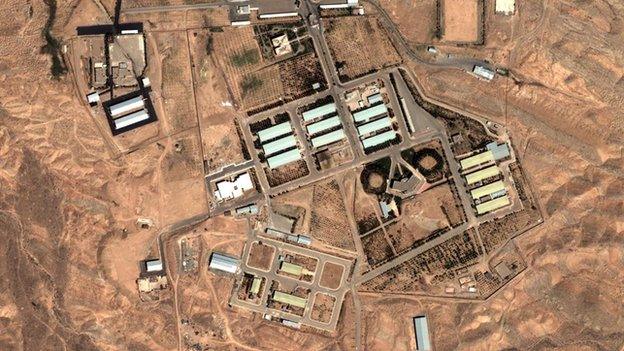

Parchin - Military site

The complex at Parchin, south of Tehran, is dedicated to the research, development and production of ammunition, rockets and explosives.

Concerns about its possible role in Iran's nuclear programme emerged in 2004, when reports surfaced that a large explosives containment vessel had been built there to conduct hydrodynamic experiments.

The IAEA has warned that hydrodynamic experiments, which involve high explosives in conjunction with nuclear material or nuclear material surrogates, are "strong indicators of possible weapon development".

In 2005, IAEA inspectors were twice given access to parts of Parchin and were able to take several environmental samples.

A report issued in 2006 noted that they "did not observe any unusual activities in the buildings visited, and the results of the analysis of environmental samples did not indicate the presence of nuclear material".

But suspicions about Parchin persisted and the IAEA repeatedly sought to visit the facility again. After requesting access in late 2011, the IAEA observed extensive landscaping, demolition and new construction at the site. In February 2012, inspectors were turned away.

The IAEA subsequently complained it had been unable to "provide credible assurance about the absence of undeclared nuclear material and activities in Iran" and that it continued to have "serious concerns regarding possible military dimensions to Iran's nuclear programme".

Under the July 2015 JCPOA, IAEA inspectors will also be able to request visits to military sites. However, access is not guaranteed and could be delayed.

The IAEA's director general, Yukiya Amano, has signed a "roadmap" with Iran calling on the agency to resolve any outstanding concerns by the end of 2015.

Qom - Uranium enrichment plant

In January 2012, Iran said it had begun uranium enrichment at the heavily-fortified underground Fordo facility, near the holy city of Qom.

It began building the site in secret, but was later forced to acknowledge its existence after being confronted with satellite imagery evidence in September 2009.

In June 2011, Iran told the IAEA that it was planning to produce medium-enriched uranium, which has a 20% concentration of U-235, at Fordo.

Iran said the enriched uranium would be used as fuel the Tehran Research Reactor. But uranium with a concentration of 20% can also be further enriched to 90%, or "weapons-grade".

Under the November 2013 interim nuclear deal, production of medium-enriched uranium ceased at Fordo, and Iran turned its stockpile into forms that were less of a proliferation risk.

The July 2015 JCPOA states that no enrichment will be permitted at Fordo for 15 years. The facility will instead be converted into a nuclear, physics and technology centre. The 1,044 centrifuges allowed to be installed at the site will produce radioisotopes for use in medicine, agriculture, industry and science.