Case studies: African migrants smuggled into Israel

- Published

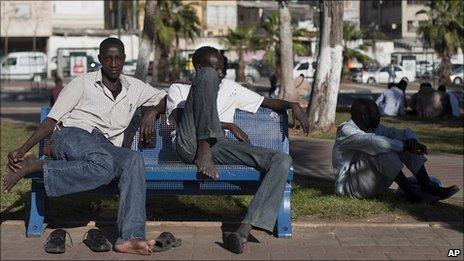

African asylum-seekers seeking casual work wait in Levinsky Park, Tel Aviv

African migrants in Israel are worried after the government announced plans for a large new detention centre in the southern Negev desert and started work on a barrier to seal off the border with Egypt.

Officials say more than 35,000 people have crossed the Sinai to enter Israel illegally in the past few years. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said those fleeing persecution would be allowed to stay, but that illegal migrant workers were a "serious threat to the character and future" of Israel.

Rights groups say most asylum-seekers have escaped conflicts in Eritrea and Sudan. No official process is in place to consider them as refugees.

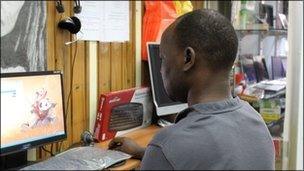

Darfuri computer shop owner, Tel Aviv

"Most of my relatives were killed in attacks on our village after the Janjaweed [militia] was formed in the hands of the Sudanese government.

In 2002, my seven-year-old daughter was wounded by a gunshot and I had to take her to the hospital in Khartoum. After her surgery I heard I would be arrested if I went home. I was able to get a passport in a different name and we escaped to Egypt. We spent two years there before my wife and other children were able to join us.

We were hoping to resettle overseas through the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) but there were many delays. Then in 2005, there was a crisis in Cairo. Many refugees were killed in a protest. It was after this that a lot of Sudanese decided to come to Israel.

Many Israelis say they identify with Darfuris, seeing them as survivors of a genocide

The journey you make is between life and death. We went in a bus to Sinai then changed to a pick-up and had to lie down hidden under cartons. We went on rough roads to avoid checkpoints and travelled at high speed for six or seven hours. Then in the mountains we waited for a full moon so we could cross the border. I paid the Bedouin $700 (£450) but he wanted more so he took all the clothes I was carrying.

In Israel we spent about 24 hours in a cell but then we were put in a nice hotel in Beer Sheva because there were so many refugees. We were taken away by activists to Jerusalem and we staged a demonstration outside the Knesset. Afterwards an Israeli family hosted all six of us in their house for 10 days until we found an apartment in Tel Aviv in August 2007. It was really unforgettable.

I have worked in a hotel and a restaurant. At one time I had no work for three months [and] that was very difficult. My field is as a computer technician and I helped set up a service for the Darfur community offering computer classes while volunteers from Tel Aviv University taught us Hebrew. Later I set up my shop repairing computers.

There was more good feeling towards people crossing the border when I came than there is now. I went to a lot of meetings in synagogues and I realised that most of the Jews who came here had escaped from problems in Europe. There was a lot of comparison to the situation in Darfur. I was given temporary citizenship with over 400 Darfuris. I have to reapply every six months.

[Now] I don't know what's going to happen. There is a camp being arranged to take all the refugees there, I feel I could also be included."

Eritrean man, Tel Aviv

As a university student [in Eritrea in 2006], I tried to join a protest and was put in a military camp for three years. It was then that I made the risky decision to cross into Ethiopia. I was in a refugee camp there for about a year but still I didn't feel safe, so I decided to head to Sudan and on to Israel. I knew that Israel was a democratic country with proper laws and thought it would give me better protection.

Often asylum-seekers, like this Eritrean woman, suffer injuries while crossing into Israel from Egypt

It took seven days to travel from Sudan to the Sinai with Bedouin people smugglers. It's a big business for them. At that time I paid $2,000 (£1,282) with help from my relatives back home. The desert is dangerous but I crossed without losing my life thanks to God. I made it to Israel in 2007.

When I crossed the border I was caught by the Israeli army but I was not put in jail. For two weeks they kept us at an army base giving us food and medication. Eventually they drove us to Beer Sheva and told us to get on a bus to Tel Aviv or Jerusalem. I was surprised.

I came to Tel Aviv and was shown to a shelter that used to be near the bus station. Back then I was able to go to the UNHCR and register as an asylum-seeker. Now the system is different. It seems to me there is no policy on refugees. It's not like in Europe or parts of Africa where they have procedures. We keep hearing from the ministry of interior that we are considered as economic migrants not political refugees.

I love Israel and care about its security but I am worried that now officials are trying to scare people by saying the black Africans are coming to take over. Eritrean people are in shock. We worry we will be put back in the hands of dictators."

Segal Rosen, Hotline for Migrant Workers

A sign in the Hotline for Migrant Workers' office points to the Saharonim detention centre.

"The main problem for asylum-seekers is that the Israeli government looks at them as 'work infiltrators', while we know that the majority from Sudan or Eritrea are refugees and should be treated as such.

Right now, out of 34,000 asylum-seekers, 20,000 are from Eritrea and 10,000 from Sudan. For the last few years, Eritreans and Sudanese have been given the right to stay but have not been given individual refugee status determination. Last year only two refugees were recognised. This is what makes it possible for the interior minister to say that only 0.01% of those crossing are "refugees".

The government is planning to build a camp near the southern border with Egypt. The idea is not to let asylum-seekers work and push them to live in this camp until there will be a place to deport them to. They're talking about building a camp for 10,000 people in six months.

What are they going to do with the 24,000 without work or a place in the camp? We know it's impossible to send them back to Sudan and Eritrea. We are very afraid that when these people are locked on the border they will not be able to approach human rights organisations for assistance. We also worry that there will no gate in the fence to accept genuine refugees.

Non-governmental organisation workers give legal advice and other support to asylum-seekers

The first people who arrived from Darfur in 2005 to 2006 mostly made a very hard journey crossing the desert by foot at night by themselves. They had Egyptian soldiers shooting at them. Some were killed and some went to prison. We know from international organisations that Egypt sent some people back to countries where they face danger.

In the last year or so, the smuggling networks of the Bedouin have developed greatly and now most people are paying them perhaps $2,000 to cross the desert. We also hear they are often being locked in desert camps, tortured and forced to get relatives abroad to send more money. Women are raped... we have had horrible stories from women who arrive pregnant and from men who arrive injured. They tell us about others who died in the desert."

Oscar Olivier, activist from Democratic Republic of Congo

"I've been in Israel for the past 16 years. The situation is a little better than when we came, when there was nobody to turn to. We survived by working here and there. We were considered foreign workers until 1999 when the UNHCR opened an office in Jerusalem. Now there are more human rights organisations who present the issues of refugees to the public and the government.

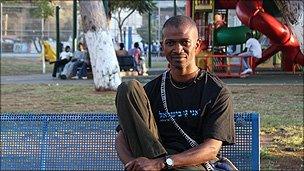

Oscar Olivier is waiting to be recognised as a refugee, 16 years later

I came first to Tel Aviv with a visa. This is where most refugees are living and they help each other. Have I been integrated into Israeli society? Yes and no. Since I managed to learn Hebrew, it's a little bit easier, and I represent the issues of the refugees to the authorities and the media. At the same time I have never had my refugee status confirmed. The interior ministry has not checked my file in 10 years.

The hostility towards refugees is quite high and it is growing. We have a different colour of skin, we speak the local language with a different accent when we manage to speak it, we think differently and we don't practise the same religion. At the same time refugees are wanted as scapegoats when a politician fails to fulfil his promises. This message is sold easily to the population. Everybody who is not working can blame the refugees taking their jobs and their money. There are now some areas of town where the residents refuse to rent apartments to refugees.

In the Middle East, Israel remains the place where there is a rule of law and when you are searching for refuge this is what you look for. However when it comes to refugees, it seems things are handled with feelings. What I would like to see is the law prevailing."

- Published15 December 2010

- Published6 June 2010

- Published22 November 2010

- Published8 December 2010