Tahrir Square's place in Egypt's history

- Published

- comments

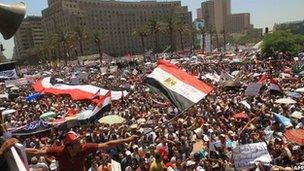

Protesters celebrated in Tahrir Square after President Mubarak stood down.

Tahrir Square - the sprawling, usually traffic-choked plaza at the heart of Cairo - became the hub of the revolution which unseated President Hosni Mubarak on 11 February.

Crowds grew to hundreds of thousands as they demanded an end to Mr Mubarak's 30 years of autocratic rule.

About 850 people were killed during the 18-day uprising in January and February.

Since then, the square has periodically become a rallying point for the protesters, mainly to express dissatisfaction with the interim military government.

In mid-November three days of deadly unrest followed protests in the square, leaving at least 30 people dead.

Symbolic square

The square has been both a practical and symbolic home of the movement - large enough to accommodate the movement's masses, and with a prominent role in the country's history of change and tumult.

The square is surrounded by some of the most important buildings in Cairo - the national museum, the colossal Mogamma administrative building, the former headquarters of the ruling NDP party (which was torched during the uprising by protesters), state TV and several glitzy international hotels.

"Whatever happens in Tahrir Square immediately becomes a national concern," the national daily al-Ahram was quoted as saying.

Gateway

Lying in the bed of a now-shrunken Nile, the site of the square has been an integral part of Cairo for centuries.

Its location is key, acting as a gateway to the city centre and to the western expansion of Cairo across the Nile.

It did not assume its current shape until the latter part of the 19th Century when another Mubarak - Ali Pasha Mubarak - was charged with remodelling Cairo after Paris at the behest of ruler Ismail Pasha.

The square ("midan") was known as Midan Ismailiya until the 1952 revolution and overthrow of the monarchy. It was renamed Midan Tahrir - Liberation Square - under President Gamal Abdul Nasser, who redeveloped it again, tearing down hated barracks which had once housed occupying British troops, and "liberating" the square and the city from its past.

The square has been the traditional gathering place for Cairenes with a grievance - from the bread riots of 1977 to the protests against the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

Some point out that the square's function as a gigantic traffic roundabout makes it an inhospitable gathering point for pedestrians, and that protests there tend to snarl up traffic flow for miles around.

As one blogger put it, external, "downtown Cairo is contested space, between the rich and the poor, government agencies and private interests, pedestrians and motor traffic, street vendors and shopkeepers".

But protesters who use the square as a platform to make their own demands can be hopeful that their voices will reverberate around Egypt.

'Second Revolution' call

Muslim Brotherhood supporters at one of the largest protests since President Mubarak was toppled.

In the weeks after the fall of Hosni Mubarak, thousands continued to gather in Tahrir Square. In an address there on 4 March, the new Prime Minister, Essam Sharaf, pledged to meet the demands for democratic change sought by protesters, and to resign if he failed.

The army cleared Tahrir Square of remaining demonstrators on 9 March. But 10 days later, thousands were back, protesting that a referendum on constitutional changes did not go far enough.

One person was killed as crowds flooded back into Tahrir Square on 9 April, to demand that Mr Mubarak and his family be put on trial.

Protesters reoccupied the square on 8 July, some calling for a Second Revolution. But the mainly secular coalition of human rights group fell out, especially after a march on the military headquarters turned violent.

Tens of thousands packed Tahrir Square at the end of the month - mainly supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood - to call for an Islamic state and Sharia law, the movement's first big show of strength since President Mubarak fell.

But a few days later, security forces used armoured vehicles to clear the tents of the few hundred remaining secular protesters, with many onlookers apparently cheering the troops.

Witnesses said activists were beaten and had their telephones broken. The BBC journalist Shaimaa Khalil was detained for 20 hours while reporting on the operation to clear Tahrir Square.

Bloody unrest

The Israeli embassy was attacked on 9 September, after crowds gathered in Tahrir Square following Friday prayers to demand faster political reforms. Three people died in the riots that followed and over 1,000 were injured.

In early October, thousands protested in the square, demanding a transfer to civilian law, after the military government proposed setting aside one-third of seats in parliament for independent candidates. Opponents feared that could allow supporters of Hosni Mubarak to return to power.

On 18 November, Tahrir Square again became the focal point as demonstrators from across the political spectrum gathered to protest against proposed constitutional changes, which they view as an attempt by the military to entrench its power.

Three days of deadly unrest followed, in which at least 30 people have been killed.