Syria: Why is there no Egypt-style revolution?

- Published

There is lots of talk of politics on the streets of Damascus. Clip courtesy YouTube

As Syrians eagerly follow developments in the Middle East, they are - for the first time in almost four decades - also loudly discussing the politics at home.

Everyone in Syria seems to be watching and waiting; people from all sections of society and every political stripe.

"One thing everyone agrees on is that change should be fast and tangible, it cannot wait," says Kais Zakaria, a 35-year-old dentist.

There are signs that the wave of change in the Middle East is having an effect here.

Last month, a demonstration took place in the old market in Damascus.

Angered by an altercation between the police and a market trader, hundreds gathered around to stop the policemen's heavy handed response.

The video quickly made the rounds on YouTube, external.

"Thieves, thieves," people shouted at the police.

"Syrians shouldn't be humiliated," they chanted.

Emboldened

Scenes like this are almost unheard of here, but Syrians - especially the youth - seem to have a newfound confidence.

They are unhappy with the tough economic outlook and the lack of political freedoms.

On the day of the demonstration, the minister of interior personally went over to talk to the protesters.

The policemen who attacked the trader were punished.

"There is a wide gap between the government and the people in Syria," says Mr Zakaria, while sipping his coffee and surfing the news at a downtown internet cafe.

"We need to regain trust in the government… To start with, we need better living conditions and fair distribution of the country's wealth," he adds.

At a nearby fruit and vegetable market, buyers and sellers are fighting over food prices. No one is satisfied.

"I can barely get my bread," one of the sellers shouts above his customers.

"I fought the Israelis in 1973, and now I am humiliated by the police.

"Why should I take it?"

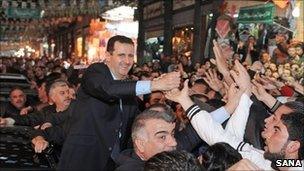

President Assad's supporters were out in force during a recent religious celebration

Cosmetic changes?

The government has taken several measures in the wake of Tunisia and Egypt to reduce the cost of basic goods, especially food.

There have been grants for the poor, and reports that civil servants have been instructed to treat citizens with respect.

But Syria suffers from corruption that goes all the way up the system.

The government is stepping up campaigns to fight it, but some figures close to the regime remain untouched.

The US Treasury has accused Syria's most powerful businessman, Rami Makhlouf, of involvement in corruption.

It describes him as a "regime insider [who] improperly benefits from and aids the public corruption of Syrian regime officials".

Mr Makhlouf, who is the president's cousin, has rejected the accusations.

But many here believe that, without the rule of law, any change will be cosmetic.

Still, there is the sense on the streets of Damascus that demonstrations will not be seen in the capital anytime soon.

There were calls last month for a "day of rage" - mainly organised by exiled opposition groups - but no-one showed up.

Recently, a second call for a day of rage was sent out on Facebook. No date has been set.

The absence of any real opposition inside the country and fear of the security services were blamed for their lack of success.

So far, there have been few calls for President Bashar al-Assad to step down. Although Syria faces similar problems as Egypt and Tunisia, the young president enjoys popularity here.

Since inheriting power from his father in 2000, he has introduced gradual reforms that have helped to revive the once stagnant economy and open up the media.

That has been enough to satisfy many.

Syrians have been hit by rising prices

"Any change should come from inside and according to people's needs, not from any external pressure," says Wadah Abed Rabboh, editor-in-chief of the pro-government al-Watan newspaper.

He admits that change was slow to come, but says more reform is in the works, including a new multi-party system.

Currently, Syria is run by a one-party system and has been under emergency law since 1963.

Political activity and freedom of expression are severely curtailed.

Thousands are reported to be imprisoned for their political views and many others are banned from travelling.

Last week, dozens of young sympathisers of the Libyan protests held a peaceful demonstration in Damascus.

It only took one person to violate the security instructions and several people were brutally beaten by the police.

Some were arrested, but released shortly after.

"We need political reforms, fair and free elections, and we need to be part of building our country," says Mr Zakaria.

President Assad's second term will end in 2014.

And this year, Syria is due to hold municipal and parliamentary elections.

Many people now believe there is a golden opportunity for change and for a peaceful transition to a democratic system.

- Published11 February 2011

- Published31 October 2010

- Published7 August 2010