History's lessons: Dismantling Egypt's security agency

- Published

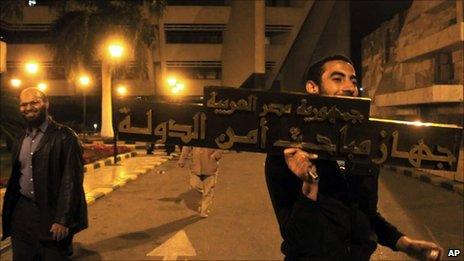

A protester carries away with the SSI sign after Egyptians stormed the building

The task of dismantling Egypt's repressive security service may seem immense, but Middle East analyst Omar Ashour draws lessons from other once feared and hated secret services around the world.

History does repeat itself.

The evening of 5 March in Egypt was much like that of 15 January 1990, when thousands of German protesters stormed the headquarters of the State Security Ministry (Stasi) in Berlin.

The direct causes of the protests were shockingly similar - state security officers were seeking impunity by destroying files that documented corruption and repression. Consequently, citizens gathered and tried to safeguard the incriminating evidence.

Fortunately for the Stasi, YouTube and Facebook did not exist in 1990. Unfortunately for Egypt's State Security Investigations (SSI), they did.

Secret graveyards, medieval-like dungeons, files of political dissidents held for more than a decade, lists of informants - celebrities, religious figures, talk-show hosts and "opposition" leaders - were all captured on camera and uploaded onto the popular websites.

"I spent 12 years in the political section of Liman Abu Zaabal prison - without charge, without visits," former detainee Magdi Zaki told local media.

"When I saw my two kids I did not recognise them and they did not recognise me. But worst of all was the month I spent in the state security building," he said.

There are reasons for this.

'Red lines'

Torture rooms and equipment were captured on camera in every SSI building stormed by protesters.

Unfortunately for the SSI and its last head, Gen Hassan Abd al-Rahman, who ordered the destruction process, reassembling the enormous amount of shredded files will not take a decade like in the case of the Stasi. Advanced computer-assisted data recovery systems exist now.

For many Egyptians, the sheer size and the graphic details of the released files were shocking.

The unlawful detentions, kidnappings and disappearances, systematic torture and rape, and the inhuman prison conditions have all been well documented since the 1980s, by both human rights organisations and Egyptian courts. But many media outlets did not dare to address those "red lines".

Amateur video purportedly shows protesters raiding ministry and secret police offices in Cairo

Aside from the horrific stories, more mundane matters help to illustrate how Egypt was run under Mubarak.

In early 2000, I met an SSI general who effectively ran Cairo University. The intellectually unsophisticated general - to put it mildly - decided which dean should run which school, which professors got hired, fired, or promoted, and which students should discontinue their education.

Never openly discussed before, these former "red lines" are now being exposed.

"The fall of the state of state security" was the headline of al-Ahram newspaper, the one-time mouthpiece of the Mubarak regime.

Lessons from abroad

Democratisation processes have at least four phases: dictatorship removal, transition, consolidation and maturation.

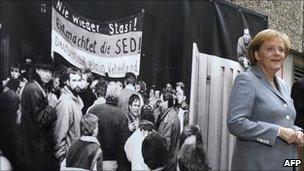

German Chancellor Angela Merkel visits the Stasi archives in Berlin

With the fall of the SSI, Egypt seems quite close to completing phase one of its inspirational struggle for democracy - the removal of its dictator and his coercive apparatus, one that behaved more like a crime syndicate than a professional security service.

But moving into the transitional phase will require institutional and legal reform.

The experiences of other countries - notably Chile, Indonesia, South Africa, East Germany, Argentina, Spain, and South Korea - are quite useful.

Comprehensive security sector reform (SSR) was at the core of democratisation in those countries. It targeted the intelligence services, police, judiciary, prison system, and the civilian management of the security services.

The core idea of the reform was simple: the security of the individual citizen is the primary objective of the security apparatus, not the security of the regime or any other entity.

This simple idea reverses the reality in Egypt, where the principal threat for many law-abiding citizens was not al-Qaeda or the Mossad, but the SSI and other Egyptian police institutions.

Final stages

In the aforementioned countries that moved into the transitional phase, the SSI-equivalents were dismantled - the Stasi in East Germany, the Bakorstanas in Indonesia, and the National Centre for Intelligence (CNI) in Chile.

The accompanying emergency laws were also annulled, most notably Indonesia's notorious 1963 Anti-Subversion Law.

A third critical step in security sector reform is the continuous monitoring of security agencies by elected parliamentary committees.

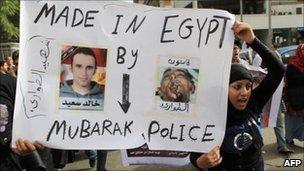

The death in custody of Khaled Said last year was an early rallying point for Egypt's revolutionaries

In Indonesia, parliamentary oversight was introduced under President Abdurrahman Wahid (1999-2001). As a result, three parliamentary commissions monitor every security apparatus in the country.

In Chile, the Senate approved the creation of a civilian National Intelligence Agency (ANI) and, by law, all security agencies have to provide any requested information to that body.

Even highly professional security agencies in the West are monitored. The British MI5, for example, is overseen by the Intelligence and Security Committee that comprises nine parliamentarians drawn from the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

A fourth critical step is dealing with gross violations of human rights committed by the SSI against Egyptians.

In that regard, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, akin to that of South Africa, may be essential to form a restorative justice system for the victims. Victims would be invited to share their testimonies, while perpetrators of gross violations could give their statements and apply for amnesty.

Overall, despite the numerous hurdles along Egypt's road to democratisation - including attacks by remaining elements of the security forces against mosques, churches and pipelines - the country seems to be on the right path.

The dismantling of the SSI, the annulment of emergency law, the parliamentary oversight of security apparatuses, and the formation of a reconciliation commission will usher in a democratic transition in Egypt.

Omar Ashour is a lecturer in Middle East Politics and Director of the Middle East Graduate Studies Program at the Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, University of Exeter (UK). He is the author of The De-Radicalisation of Jihadists: Transforming Armed Islamist Movements.

- Published5 March 2011