Polarisation and violence grows in Syria

- Published

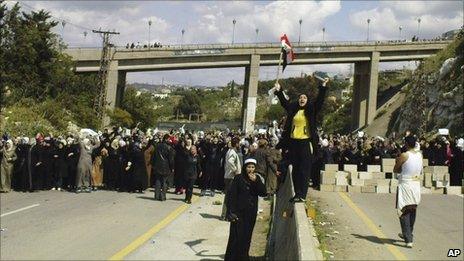

Anti-government demonstrations have touched almost every corner of Syria

After a month and an estimated 200 or more deaths, Syria's unrest is showing no sign of going away.

If anything, it is spreading, and getting uglier by the day.

It does not yet seem to have reached that point of critical mass which saw vast human tides of protesters sweep away the rulers of Tunisia and Egypt, whose armies refused to stand by them and shoot their own people.

But what began in March as a minor incident involving schoolchildren daubing graffiti on walls in the southern city of Deraa has led to disturbances and deaths in virtually all parts of the country.

The uprising has yet to take a serious grip on the two biggest cities, Damascus and Aleppo.

But despite a massive security presence, Damascus University students have staged demonstrations. On Wednesday there were similar scenes as Aleppo joined the long list of places where protests have been suppressed.

There is no mistaking the fact that the Baathist regime of President Bashar al-Assad feels itself under threat.

The official media are geared to portray the troubles as an externally-driven campaign by terrorists and gangsters to undermine the country's security, stability and unity.

On Wednesday, three men said to have been captured during disturbances appeared on Syrian state TV to "confess" that they had been paid and armed by outsiders to open fire on demonstrators and security forces.

They said their sponsors were linked to the Muslim Brotherhood and that guns and money had come across from Lebanon, sent by a member of parliament close to caretaker Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

The MP, Jamal al-Jarrah, dismissed the confessions. They were also denied by the Muslim Brotherhood, which described them as "media fabrications designed to escape the pressure for reform".

The Brotherhood, rooted in the majority Sunni community, was ruthlessly suppressed after uprisings in Syria in the early 1980s, culminating in the virtual razing of the city of Hama in 1982.

By exploiting these "confessions", the media campaign clearly aims to dismiss the protests as the work of hired agitators and armed gangs.

Show of support

The same "armed gangs" and saboteurs are also officially blamed for the announced deaths of around 35 named Syrian army and police personnel who were reportedly shot dead - and many more wounded by gunfire - over the past week.

The funerals of slain soldiers have heavily featured on state TV to drum up support for the government

Official media say 19 policemen were killed in Deraa last Friday and nine soldiers died in an ambush near Banias on Sunday, with another one shot dead there by gunmen on Tuesday and another half-dozen officers killed and more than 160 injured in other parts of the country.

Their funerals have also been heavily featured on Syrian TV, with crowds of mourners (many in uniform) chanting pro-regime slogans and tearful relatives pledging unwavering loyalty to Mr Assad.

There is no reason to disbelieve the deaths of these named police and army personnel. The question remains: who is shooting them?

For the regime, the answer is simple: "armed gangs" who are fomenting unrest as part of a foreign plot.

But the protesters insist that their movement is peaceful and unarmed. Their social media and website outlets have repeatedly warned that anybody posting messages advocating violence or sectarianism will be banned and blacklisted.

Some have suggested that the police and soldiers who have died were shot by some of the 17 or so different intelligence and security branches or the Alawite militia known as the "Shabbiha", in order to discredit the protests and frighten people with the threat of armed anarchy and a takeover by Sunni militants.

That was also suggested by an "intelligence document, external" published on one of the main opposition pages on Facebook which purported to outline the regime's detailed plans on how to handle the unrest - though the document has been generally dismissed by opposition circles themselves as fabricated.

Algerian scenario

Protesters have also suggested that some of the servicemen were shot by their own officers for refusing orders to shoot at demonstrators.

"They are following the Algerian scenario, using armed attacks to dismiss protests as 'terrorist' and justify collective reprisals," said one opposition figure.

At the same time, beneath the propaganda manoeuvring and security moves, Mr Assad does appear to recognise that he faces a genuine internal problem with demands for change and reform.

Although the move is largely cosmetic, he has fired the incumbent government and a new administration was announced late on Thursday.

A deadline of 25 April has also been set for measures to be formulated towards lifting the state of emergency that has been in place since 1963, and diluting the monopoly of the ruling Baath party by permitting other political groups to function.

Mr Assad has also dismissed several provincial governors and has been discussing demands with a delegation of leaders from Deraa, which remains the epicentre of dissent, as well as other places.

But with protests set to continue, there remain serious doubts about whether Mr Assad can deliver reforms serious enough to placate the apparently growing opposition and public anger.

Some opposition figures believe he could still turn the situation around, but only by taking steps they believe he is not strong enough to tackle, such as getting rid of close family members who are figures of hate for the protest movement.

They include his brother Maher, who commands two elite military units regarded as the regime's Praetorian guards, his brother-in-law Assef Shawkat, who is deputy chief of staff of the armed forces, and his cousin Rami Makhlouf, who is involved in lucrative financial operations.

Foreign interest

As the struggle continues and more blood flows, Western countries have been tepid in their response. There is little chance of intervention as is happening in Libya.

Even at the height of US ambition in the region, culminating in the overthrow of Saddam Hussein in Iraq in 2003, the idea of toppling Mr Assad's regime did not gain much support because of fears of a radical Sunni takeover - a fear the regime can play on both externally and internally.

Conversely, Syria's regional friends are rallying to its defence. Having encouraged similar protest movements in Egypt and Bahrain, Iran - long a strategic ally of Damascus - has declared the unrest in Syria part of a foreign conspiracy to weaken its resistance to Israel.

According to US administration officials quoted by the Wall Street Journal, Tehran has also sent crowd-control equipment to Syria and offered help in monitoring opposition activity, expertise which paid dividends during Iran's own so-far successful campaign to suppress similar pro-democracy dissent after the 2009 presidential elections.

The repercussions of events in Syria are being strongly felt in Lebanon, where Syrian influence continues to play a huge role despite the withdrawal of troops in 2005 after nearly 30 years.

Hezbollah, in whose creation in the early 1980s the Syrians were instrumental, has been giving full propaganda support to Mr Assad.

A change of regime in Damascus would clearly have a massive impact on Lebanon and on the wider regional strategic balance, reshuffling the cards in ways that are as hard to predict as the eventual outcome in Syria itself.