Profile: Yemen's Ali Abdullah Saleh

- Published

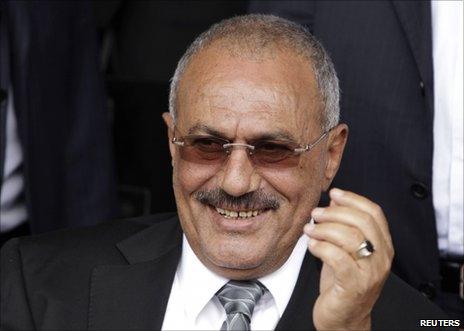

Mr Saleh may not be returning to Yemen after his wounds heal, some analysts say

Ali Abdullah Saleh has proved to be one of the Arab world's most tenacious leaders, projecting a statesman-like, even affable, image in the face of popular opposition, in sharp contrast to some of his counterparts during the "Arab spring".

While Yemen has seen the bloody repression of protests in its capital Sanaa and other cities, the country's president has sought - with diminishing success - to distance himself from the violence.

But the country's strife finally caught up with him personally when he was wounded on 3 June in an attack on the presidential mosque in Sanaa that wounded several government officials and killed seven bodyguards.

The following day, Mr Saleh was flown on a Saudi medical plane to Riyadh to receive medical treatment for shrapnel wounds and burns.

Mr Saleh accepted but then declined to sign a regional plan for ending the conflict. Under the plan he would step down in return for immunity from prosecution and handover power to his vice president, Abdrabo Mansour Hadi.

Critics say that over more than three decades at the top, he used every means and loophole to stay in power, promising to exit politics only to bide his time in an effort to prolong his rule.

"[He] has always ruled by creating confusion, crisis and sometimes fear among those who might challenge him," Yemen expert Sarah Phillips wrote in an article for the UK's Guardian newspaper, external.

Mr Saleh has led one of the most challenging countries in the region, an impoverished state vulnerable to militancy, positioned between the oil-rich authoritarianism of the Gulf states and the lawlessness of Somalia, and still healing from a Korea-like division during the Cold War.

Now approaching his 70th year, he has likened the task of ruling Yemen to "dancing on the heads of snakes".

Balancing act

The modern Republic of Yemen is inextricably linked to Mr Saleh, elected its first president after unification in 1990.

Born in Sanaa and receiving little education, he worked his way up through North Yemen's military, being wounded during the 1970 civil war between republicans and Saudi-backed royalists.

He took part in a coup four years later and assumed his first national leadership role in 1978, when parliament endorsed him as president.

The next 12 years saw the painstaking work of unification with Marxist South Yemen, a process which briefly appeared to collapse in 1994 when civil war flared up.

Abroad, Mr Saleh largely achieved the delicate task of keeping both Western and Arab powers on side.

His battle to control al-Qaeda - who have sensed in Yemen a base comparable to Afghanistan in the late 1990s - won him friends in Washington.

The Americans might otherwise have been wary of a leader who had stayed close to Iraq's Saddam Hussein during the occupation of Kuwait.

Turning point

The spectre of civil war is something Mr Saleh has continued to conjure up in a bid to justify his hold on power.

"They [the opposition] want to drag the area to civil war and we refuse to be dragged to civil war," he said in a speech on 22 April, the day before news broke that he had agreed to leave power imminently.

"Security, safety and stability are in Yemen's interests and the interests of the region."

The shooting of 45 people by snipers at an opposition rally in Sanaa on 18 March had proved a turning-point for many, despite his denials that his security forces had taken part.

Ministers and ambassadors abandoned him in protest, and the crowds in the streets swelled in the weeks that followed.

With outrage now added to anger at corruption and poverty he had failed to tackle for decades, Mr Saleh's "snake-dancing" days looked to be nearly over.

Some analysts doubt he will make a return trip to Sanaa to resume power once his wounds have healed.

- Published23 April 2011