Family dynamics drive Syrian President Assad

- Published

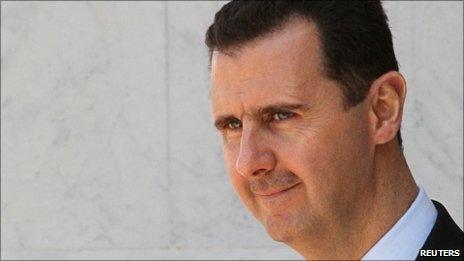

As Syrian President Bashar al-Assad struggles to put down widespread protests against his government, the BBC's Kim Ghattas examines the family intrigue constraining his actions.

Scour the net for information about what might be happening inside Syria, the regime and the Assad family and you will find the wildest rumours.

Maher al-Assad, the president's brother and head of the presidential guard, has been caught by defecting soldiers. Or, he's about to stage a coup against Bashar.

Vice-President Farouk al-Sharaa has been killed. The Deputy Foreign Minister Faysal Mekdad has disappeared.

The wild speculation is partly explained by the almost non-existent access international journalists have had to Syria since the protests started.

Syrian officials who usually interact with international media have also mostly failed to take phone calls or answer e-mails.

Family rule

For years, the outside world has tried to divine who is winning the internal struggles inside Syria, an opaque country, and the Assad clan.

The violent turn of events in Syria now has people wondering not only what might happen next but also what went wrong with outside assessments of Bashar al-Assad as a leader.

For years, the West pinned high hopes on Mr Assad, a quiet ophthalmologist who trained in London for about 18 months.

The US, France and the UK expected the Westernised-looking leader to open Syria up to the West. But 11 years after he came to power, change has been minimal and mostly cosmetic.

A common explanation had Mr Assad as a reformer who understood it was in Syria's interest to align itself with the West but was constrained by his father's conservative old guard.

While this may have been true in the first few years of his rule as Mr Assad found his footing, by 2005 there was no-one left from the old guard, according to Ayman Abdelnour, a university friend of Mr Assad who was also one of his presidential advisers for several years.

Mr Abdelnour has been living in self-imposed exile in the United Arab Emirates since 2007.

According to him, any old faces, like adviser Buthaina Shaaban, Vice-President Farouk al-Sharaa or even Foreign Minister Walid Muallem, were powerless but stayed on because they benefited from the system.

In the process, the ruling Baath party was also weakened while business deals and corruption took over as means to consolidate power.

"Power is totally concentrated in the hands of the family," said Mr Abdelnour.

"There is total solidarity between them and he is the president, like a board chairman, they discuss things and make a decision together."

A source close to the Assad family, who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity for safety reasons, said there was "full co-ordination between Bashar and his brother Maher" who heads the feared Republican Guard.

Road to Damascus

Senator John Kerry was one of those convinced of Mr Assad's desire for change and repeatedly encouraged engagement with Damascus under the Obama administration.

Mr Kerry travelled to Syria a number of times, had dinner with Mr Assad and his wife Asma and attempted to get talks going between Syria and Israel.

Hope of a peace deal between the two enemies has sent many Western politicians on the road to Damascus.

As late as mid-April, while protests were gathering pace in Syria, Mr Kerry suggested it was up to the West to offer more to Mr Assad so he could turn his back on his current ally, Iran.

Demonstrations against the Syrian government have continued despite tough security measures

In Syria, many people, too, had hoped Mr Assad would improve their lives.

But his image of a benevolent leader, frustrated by an old guard in his attempts to bring change to the country, was a well-studied tactic, according to US-based Syrian dissident Ammar Abdulhamid.

"It was the same during Hafez al-Assad's time. The idea is to always blame mistakes of the regime on others, so you can push them out and say now it will be better and have people continue to pin their hopes on the leader," said Mr Abdulhamid, who adds this worked to some extent with the general population.

But over the last few years the reality that Mr Assad was just his father's son, a tough leader putting up an act as reformer, became increasingly clear to more people in Syria who confided their bitter disappointment to visiting foreign reporters.

In his attempts to project the image of a Westernised leader that gave Western visitors a sense of familiarity, Mr Assad was helped by Asma, his pretty, London-raised Syrian wife.

The British public relations company, Bell Pottinger, also helped to make her the face of Syria's international image.

The anonymous family source suggested Mr Assad married Asma knowing she would be an asset in presenting a fresh face for Syria.

But the source also suggested Asma's approach to her role as first lady caused tension within the Assad family, particularly with the president's sister Boushra and his mother Anisseh, who cared little about public relations.

Weak link?

Despite the friction and occasional estrangement, with Mr Assad's brother-in-law Assef Shakwat for example, the family still sticks together, along with a small coterie of relatives and security chiefs.

"They know that if one of them falls, they all fall. It's very much about family solidarity, not anymore just about maintaining Alawite rule," said Mr Abdulhamid.

But the unprecedented challenge to the Assad family's grip on Syria could increase tension or cause rifts.

While Mr Assad is seen as in control, there is also some suggestion that he is the weakest link in the family, kept in check by his brother Maher and possibly his sister Boushra.

Mr Assad the ophthalmologist was not originally destined to become president. His older brother, Basil, an army major and reportedly Hafez's favourite son, was being groomed for the job until he died in a car crash in 1994.

Basil, who often appeared in full military uniform at official functions, was a forceful character, the eldest of five children, a competitive horse rider and an aficionado of fast cars who was popular with women.

Bashar grew up in his shadow, "weak and in his own world", according to the family source and "calm with a soft voice", according to Mr Abdelnour.

"Basil was the boss," said Mr Abdelnour. "Bashar didn't like the limelight. When he became president he became very systematic about stepping up to the plate and learning how to lead."

But even though he was the next in line after Basil, Bashar was not the obvious first choice as potential successor.

Maher, who had had a military career, had been discussed as an option and the anointment of Bashar was met with some resistance, according to the family source who spoke to the BBC.

Even though the father had prepared the ground by getting rid of potential rivals, when Bashar became president he had to assert himself and show leadership.

"Bashar felt that any reform, any questioning of his way of doing things was a sign he wasn't respected," said dissident Abdulhamid, suggesting Bashar may have struggled with feelings of inadequacy or inferiority. "He refused to be treated any differently than his father."

The US and Europe are still hoping he will act differently.

On Friday, Washington imposed sanctions on his brother and his cousin but not President Assad himself, thinking perhaps it might convince him to change course.

It is an open door that the Syrian president does not appear interested in. But if he is, his family will likely pounce the moment he flinches.