Profile: Fatah Palestinian movement

- Published

The yellow banner of Fatah flies next to the Palestinian national flag

Founded by Yasser Arafat in the 1950s, Fatah was once the cornerstone of the Palestinian national cause, but its power has since faded.

Under Arafat's leadership, the group originally promoted an armed struggle against Israel to create a Palestinian state. But it later recognised Israel's right to exist, and its leaders have led Palestinian peace talks aimed at reaching a two-state solution.

Arafat signed the first interim peace deal with Israel in 1993 in Oslo, but a full accord has proved elusive, despite decades of on-off negotiations - the latest round launched by President Barack Obama at the White House last September.

Yasser Arafat shakes hands with Israeli PM Yitzhak Rabin in 1993, as US President Bill Clinton looks on

Since Arafat's death in 2004, Fatah has fallen from its position of dominance and, in 2006, lost parliamentary elections to rival Palestinian movement Hamas. In June 2007 it was effectively driven out of the Gaza Strip after violent clashes between the two factions.

Now led by another of its founders, Mahmoud Abbas, Fatah has also seen its power steadily eroded by internal divisions.

The party has been dogged by claims of nepotism and corruption in government and critics say it is in desperate need of reform.

Armed resistance

Fatah is the reverse acronym of Harakat al-Tahrir al-Filistiniya (Palestinian Liberation Movement). The name means "conquest" in Arabic.

Founded by Arafat and a handful of close comrades in the late 1950s, its leaders wanted to rally Palestinians in the diaspora in neighbouring Arab states to launch commando raids on the young Israeli state.

In 1969, Arafat took over as chairman of the PLO, the umbrella group created by Arab states to represent the Palestinians on the international stage.

But various Palestinian groups within the PLO gradually split off as Fatah proved to them either too ineffective, too corrupt, or too moderate.

By the time of the first intifada - or uprising - in 1988, Fatah's power had been significantly diluted. The party became the chief proponent of a negotiated solution with Israel, and by 1993 accepted Israel's right to exist.

The second intifada saw a number of armed groups associated with Fatah emerge, most notably the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades. The Brigades are neither officially recognised nor openly backed by Fatah, though members often belong to the political faction.

During the intifada, the Brigades carried out numerous operations against Israeli soldiers and settlers in the West Bank and Gaza, and suicide attacks on civilians inside Israel.

Israel's responses to the intense campaign of attacks in 2002 further weakened Arafat and Fatah's authority, and left the Arafat-led Palestinian Authority in disarray.

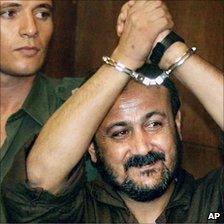

Much of the authority's infrastructure was destroyed, Arafat's compound in Ramallah was besieged for five weeks, and Israel captured Marwan Barghouti - the Fatah leader in the West Bank who Israel alleges is the head of al-Aqsa Brigades. He was later convicted of murder.

Peace track

Mahmoud Abbas (L) and Khaled Meshaal meet in Cairo in May for the first time in four years

With international pressure mounting, Fatah - though notably not the al-Aqsa Martyrs' Brigades - signed a declaration rejecting attacks on civilians in Israel and committing themselves to peace and co-existence.

In late October 2004, Arafat was taken ill and flown to France for emergency treatment. He died of a mysterious blood disorder on 11 November.

Mahmoud Abbas was confirmed as Arafat's successor as chairman of the PLO shortly afterwards and, as Fatah's candidate, won a landslide victory in the January 2005 presidential elections.

But Mr Abbas inherited a party that was divided, in need of reform, and losing its popular support.

The loss of Yasser Arafat allowed a rift to develop between the party's "old guard" of former exiles and its "new guard", led by the jailed Marwan Barghouti.

Fatah has also suffered from being associated with the perceived corruption and incompetence of the Palestinian Authority.

Hamas rift

Hamas' overwhelming victory in the 2006 parliamentary election dealt another huge blow to the group, and caused further disarray in the Palestinian Authority (PA) led by Mr Abbas.

The PA authority now extends to Palestinian-controlled areas of the West Bank, but since June 2007, it has had little sway in Gaza.

Marwan Barghouti still influences Fatah from inside an Israeli prison

Mr Abbas has overrun his term as president of the PA - it should have ended in January 2008 - drawing the legitimacy of his leadership into question.

Despite that, Mr Abbas went to Washington in September 2010, to re-launch direct peace talks with the Israelis on behalf of all Palestinians. However, the Palestinian president suspended the talks one month later after a partial freeze by Israel on settlement-building expired.

Apparently disillusioned with the peace process, Mr Abbas turned his attention to achieving a reconciliation deal at home.

In May, he and Hamas leader, Khaled Meshaal, signed a deal in Egypt's capital Cairo aimed at ending their four-year rift.

Although Palestinians have welcomed the deal, they remain sceptical about whether the two sides can iron out their differences on a number of key issues and work together for the common cause - establishing an independent Palestinian state.