Analysis: Egypt suffers post-revolution blues

- Published

The brand new offices of the Muslim Brotherhood, which was outlawed under the Mubarak regime

Three months after the popular uprising that forced President Hosni Mubarak from power, the BBC's Jeremy Bowen returns to Cairo, where the heady days of revolution have given way to old tensions and fresh concerns.

The new headquarters building of Egypt's Muslim Brotherhood is a magnificent, freshly painted office block, adorned with its symbol of the Koran flanked by two curved swords.

For anyone who visited the Brotherhood's pokey, shabby offices during the Mubarak days the place is a revelation.

The Brotherhood has a new swagger. Outside the building were shiny, expensive cars belonging to some of the businessmen who back the Brotherhood.

Inside, under golden chandeliers, sat elderly veterans of the Brotherhood's struggles on ornate sofas and armchairs, talking discreetly.

Among them, holding court, was a former leader who spent 30 years in jail.

Unusually for old men, they were discussing the future, not the past. One of the new facts of life in post-Mubarak Egypt is that so far, the Muslim Brothers are the revolution's biggest winners.

"I am very optimistic," says Osam al-Shabini, one of the group's younger activists.

"We are looking to build our country very fast, especially in the economic section and to share in all political activities in Egypt."

Sectarian strife

It is harder to find such optimism around the more secular protesters who were prominent in Tahrir Square during the 18 days in January and February that changed the Middle East profoundly.

Military police guard the damaged Virgin Mary church in Imbaba

This week the preoccupation was a series of sectarian clashes between Coptic Christians and extremist Salafist Muslims that killed 12 people, injured more than 200 and left a church gutted by fire.

Many fear that bloodshed between Muslims and Christians (who make up around 10% of the population) is just another symptom of discord in a society that is turning out to have even more serious problems than Egyptians expected.

"Sectarian violence is one of the things that scare people about what happens next," said Dina Samak, Egypt editor of al-Ahram newspaper.

"You can't have a safe transition to democracy if you have sectarian violence and Islamic political forces dominating the political scene."

One of the bellwether moments of the revolution was when al-Ahram, the regime's mouthpiece, dropped the dictator and backed the protesters.

The traffic outside the newspaper's towering, cavernous offices is worse than ever. Cairo's residents say that their fellow motorists are even less willing to follow the rules of the road than they were before.

The police have never really returned to the streets, and those who are there are not respected or even feared.

Poverty

The sectarian clashes happened in Imbaba, one of the poorest parts of Cairo. It is a quarter dominated by 10-15 storey concrete tenements.

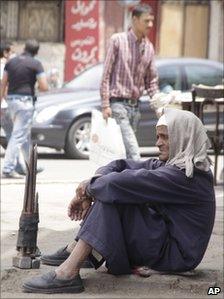

The old problems of poverty and unemployment have not gone away

Alleyways barely wide enough for a donkey cart run between them, and laundry festoons the concrete canyons.

Like everywhere poor and overcrowded in Cairo, children play near piles of uncollected rubbish, bakers' boys on bikes balance great trays of bread on their heads and the place throbs with enough human energy to power the city if somehow it could be tapped.

Life for Egypt's poor was never easy, but it has got harder since the revolution.

Food prices have doubled. Unemployment for young people hovers around 30%. Many of those who have jobs are under employed and earn very little.

The soldiers and riot police who were deployed in the area were jumpy. The military has been running Egypt since President Hosni Mubarak resigned.

Diplomats here say senior officers worry that the army was not designed to run a country in flux. The pressures of being in power, they fear, might even split middle ranking officers from the generals.

Impatience

Outside Cairo's main television centre, on the corniche that runs along the Nile, Christian protesters were chanting slogans against Field Marshal Tantawi, who heads the army council that has the real power here now.

"Tantawi, you're with the oppressors, not the oppressed," one chant went.

The crowd was just a few hundred, but the chants reflect increasing concerns among veterans of the Tahrir Square protests about what happens next.

"I am a little bit frustrated because the message that was sent from Tahrir Square - all of us uniting into one nation - is not being heard," says one protester, Fadi Phillip.

Egyptians felt a sense of national purpose during the protests in January and February

The unexpected high of the triumph over the Mubarak regime has been followed by a crashing low. The reality of trying to build a new society is much harder than expected.

But there is probably a bit too much impatience.

It has been, after all, only three months since Mr Mubarak was forced out. It is only a matter of weeks since he and his sons were placed under arrest.

Elections for a new parliament and a new president are going to be the best indication of the way that Egypt is going.

The parliamentary elections, assuming they go ahead, are due for September. The presidential poll might not now happen before next year.

The poll will be a test. Will the votes be fair? Will they happen at all? And will Egyptians, unused to an election that changes anything, be prepared to accept the results?