Dictionary of dead language complete after 90 years

- Published

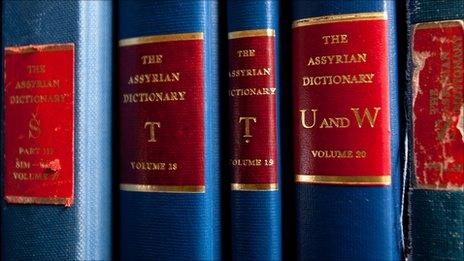

The first volumes of the dictionary were published in the 1950s

A dictionary of the extinct language of ancient Mesopotamia has been completed after 90 years of work.

Assyrian and Babylonian - dialects of the language collectively known as Akkadian - have not been spoken for almost 2,000 years.

"This is a heroic and significant moment in history," beamed Dr Irving Finkel of the British Museum's Middle East department.

As a young man in the 1970s Dr Finkel dedicated three years of his life to The Chicago Assyrian Dictionary Project, external which is based at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

That makes him something of a spring chicken in the life story of this project, which began in 1921.

Almost 90 experts from around the world took part, diligently recording and cross referencing their work on what ended up being almost two million index cards.

The Chicago Assyrian Dictionary is 21 volumes long and is encyclopaedic in its range. Whole volumes are dedicated to a single letter, and it comes complete with extensive references to original source material throughout.

It all sounds like a lot of work for a dictionary in a language that no-one speaks anymore.

It was "often tedious," admits Prof Matthew W Stolper of the Oriental Institute, who worked for many years on the dictionary - but it was also hugely rewarding and fascinating, he adds.

"It's like looking through a window into a moment from thousands of years in the past," he told the BBC World Service.

Ancient life and love

The dictionary was put together by studying texts written on clay and stone tablets uncovered in ancient Mesopotamia, which sat between the Tigris and the Euphrates rivers - the heartland of which was in modern-day Iraq, and also included parts of Syria and Turkey.

And there were rich pickings for them to pore over, with 2,500 years worth of texts ranging from scientific, medical and legal documents, to love letters, epic literature and messages to the gods.

"It is a miraculous thing," enthuses Dr Finkel.

"We can read the ancient words of poets, philosophers, magicians and astronomers as if they were writing to us in English.

"When they first started excavating Iraq in 1850, they found lots of inscriptions in the ground and on palace walls, but no-one could read a word of it because it was extinct," he said.

But what is so striking according to the editor of the dictionary, Prof Martha Roth, is not the differences, but the similarities between then and now.

Inside the Assyrian Hall of the Iraqi National Museum in Baghdad

"Rather than encountering an alien world, we encounter a very, very familiar world," she says, with people concerned about personal relationships, love, emotions, power, and practical things like irrigation and land use.

The ancient Greeks, Romans and Egyptians are far more prominent both in the public consciousness and in school and university curriculums these days.

But in the 19th Century it was Mesopotamia that enthralled - partly because researchers were looking for proof of some of the bible stories, but also because its society was so advanced.

iraqnationalmuseuminbaghdad13march2004.jpg)

An example of cuneiform script from the ancient city of Babylon

"A lot of the history of how people went from being merely human to being civilised, happened in Mesopotamia," says Prof Stolper.

All sorts of major advances are thought to have their earliest origins there, and - crucially - Mesopotamia is believed to be among three or four places in the world where writing first emerged.

The cuneiform script - used to write both Assyrian and Babylonian, and first used for the Sumerian language - is, according to Dr Finkel, the oldest script in the world, and was an inspiration for its far more famous cousin, hieroglyphics.

Its angular characters were etched into clay tablets, which were then baked in the sun, or fired in kilns.

This produced a very durable product, but it was very hard to write, and from about 600BC, Aramaic - which is spoken by modern-day Assyrians in the region - began to gain prominence, simply because it was easier to put into written form, researchers believe.

Fresh minds

With the dictionary now finally complete, "there are mixed emotions", says Prof Roth.

"As someone who has been so deeply engaged every day of the last 32 years with this project, there is a sizeable chunk of my scholarly identity that feels like it is going to be missing for a while," she told the BBC World Service.

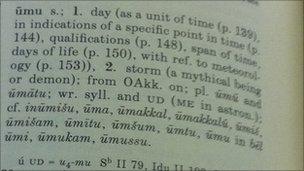

An entry from the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary

"It's a great achievement and a source of pride," adds Prof Stolper.

"It was like a living thing that grew older and changed its attitudes, that made mistakes and corrected them.

Now that it's done, it's a monument, grand and imposing, but at rest".

But those involved most closely in the dictionary, are also the first to stress its limitations.

They still do not know what some words mean, and because new discoveries are being made all the time, it is - and always will - remain a work in progress.

Prof Stolper for one says he is stepping aside; any future updates or revisions would be best done by "fresh minds" and "fresh hands", he believes.

The entire dictionary costs $1,995 (£1,230; 1,400 euros), but is also available for free online, external - a far cry from the dictionary's low-tech beginnings.

Turning philosophical, Dr Finkel reflects on the legacy of our own increasingly electronic age, where so much of what we do is intangible.

"What is there going to be in 1,000 years' time for lunatics like me, who like to read ancient inscriptions - what are they ever going to find?" he asks.

"They will probably say that there was no writing - it was a dark age, that people had forgotten it, because there may be nothing left."