Guide: Syria Crisis

- Published

The unrest began in the southern city of Deraa in March

The Syrian authorities have responded to anti-government protests with overwhelming military force since they erupted in March 2011. The protests pose the greatest challenge to four decades of Assad family rule in the country.

Here is an overview of the uprising, in which the UN says more than 9,000 people have been killed by security forces and at least 14,000 others detained. In February, the government put the death toll at 3,838 - 2,493 civilians and 1,345 security forces personnel.

How did the protests start?

The unrest began in the southern city of Deraa in March when locals gathered to demand the release of 14 school children who were arrested and reportedly tortured after writing on a wall the well-known slogan of the popular uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt: "The people want the downfall of the regime." The protesters also called for democracy and greater freedom, though not President Assad's resignation.

The peaceful show of dissent was, however, too much for the government and when people marched though the city after Friday prayers on 18 March, security forces opened fire, killing four people. The following day, they shot at mourners at the victims' funerals, killing another person.

Within days, the unrest in Deraa had spiralled out of the control of the local authorities. In late March, the army's fourth armoured division - commanded by the president's brother, Maher - was sent in to crush the emboldened protesters. Dozens of people were killed, as tanks shelled residential areas and troops stormed homes, rounding up those believed to have attended demonstrations.

But the crackdown failed to stop the unrest in Deraa, instead triggering anti-government protests in other towns and cities across the country, including Baniyas, Homs, Hama and the suburbs of Damascus. The army subsequently besieged them, blaming "armed gangs and terrorists" for the unrest. By mid-May, the death toll had reached 1,000.

What do the protesters want and what have they got?

Protesters began somewhat cautiously by calling for democracy and greater freedom in what is one of the most repressive countries in the Arab world. But once security forces opened fire on peaceful demonstrations, people demanded that Mr Assad resign.

The president has resolutely refused to step down, but in the few public statements he has made since March he has offered some concessions and promised reform. The 48-year-long state of emergency was ended in April 2011, while a new constitution offering multi-party elections was approved in a referendum in February 2012. But activists say that - as long as people continue to be killed - Mr Assad's promises count for very little.

Is there an organised opposition?

The Syrian authorities have long restricted the activities of disparate opposition parties and activists, and they played a minor role at the start of the uprising. However, as the protests spread across the country and the government crackdown intensified, opposition groups publicly declared their support for the protesters' demands and in October several announced the formation of a united front, the Syrian National Council (SNC).

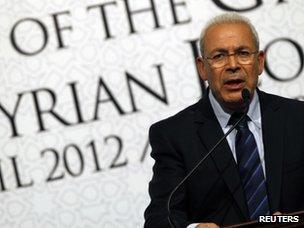

SNC chairman Burhan Ghalioun wants to unite groups seeking peaceful change in Syria

Led by the Paris-based dissident Burhan Ghalioun and including the Muslim Brotherhood, it aims to provide "the necessary support for the revolution to progress and realise the aspirations of our people for the overthrow of the regime, its symbols and its head". It hopes to offer a credible alternative to President Assad's government and serve as a single point of contact for the international community.

The SNC, which is dominated by Syria's majority Sunni Muslim community, has struggled to win over Christians and members of President Assad's Alawite sect, who each make up about 10% of the population and have so far stayed loyal to the government. The council's primacy has also been challenged by the National Co-ordination Committee (NCC), an opposition bloc that still functions within Syria and is led by longstanding dissidents, some of whom are wary of the Islamists within the SNC. Several members of the SNC have also complained about its ineffectual leadership.

The disunity has frustrated the international community, so at the end of March 2012 all the main groups, with the exception of the NCC, put aside their differences and agreed that the SNC would be the "formal interlocutor and formal representative of the Syrian people". They were also united in their scepticism at the peace plan presented by the UN and Arab League envoy, Kofi Annan.

The opposition has also found it difficult to work with the Free Syrian Army (FSA), a group of army defectors which is seeking to topple Mr Assad by force. Based in Turkey, its fighters have launched increasingly deadly and audacious attacks on security forces in the north-western province of Idlib, around the central cities of Homs and Hama, and even on the outskirts of Damascus.

The opposition has also found it difficult to work with the Free Syrian Army, a group of army defectors

In January 2012, residents of Zabadani, a mountain town 40km (25 miles) north-west of the capital, said it had been "liberated" by FSA fighters. Days later, defectors seized control of Douma, a suburb 10km (six miles) from Damascus, for a few hours. But in February 2012, government forces launched an offensive on FSA strongholds in Homs. FSA fighters staged a "tactical withdrawal" on 1 March, after a nearly a month of intense bombardment in which an estimated 700 people were killed. Two weeks later, troops took control of the northern city of Idlib from the FSA after four days of fighting, activists said.

The FSA's leader, Riyad al-Asaad, claims to have 15,000 men under his command, though analysts believe there may be no more than 7,000. They are also still poorly armed, and many have only basic training.

The FSA agreed in March 2012 to abide by the terms of Kofi Annan's peace plan, which demanded a ceasefire by all parties on 10 April. But after the Syrian foreign ministry announced on 8 April that the army would not withdraw troops and tanks from populated areas until "armed terrorist groups" had presented written guarantees of a "halt to all violence", the FSA cast doubt on the initiative. Col Asaad said that while the rebels were "committed", they did not recognise the Assad government "and for that reason we will not give guarantees".

What is the international community doing?

Syria is a major player in the Middle East. Any chaos here could cause knock-on effects in countries such as Lebanon and Israel, where it can mobilise powerful proxy groups, such as the militant Hezbollah and Hamas movements. It also has close ties with Shia power Iran - an arch-foe of the US, Israel and Saudi Arabia - which could potentially draw those powers into a dangerous Middle Eastern conflict.

The Arab League observer mission in Syria failed to halt the crackdown on dissent

The Arab League initially remained silent on the issue of Syria - although it backed the Nato-led bombing campaign against Libya's Col Muammar Gaddafi in a bid to protect civilians there. The 22-member group called for an end to the violence, but cited hesitation over any action because of "strategic and political considerations".

But in November 2011, member states led by Qatar and Saudi Arabia surprised observers by voting to suspend Syria in an effort to force President Assad to end the crackdown. The League later imposed economic sanctions when the Syrian government hesitated over allowing the deployment of an observer mission to verify its implementation of a peace initiative, which demanded the withdrawal of troops and tanks from the streets. Damascus eventually allowed in the observers in December 2011, but they failed to halt the crackdown on dissent.

In late January 2012, the Arab League laid out an ambitious plan of political reform, which called on President Assad to delegate power to a vice-president, to engage in proper dialogue with the opposition within two weeks, and form a government of national unity in two months. The League said this should eventually lead to multi-party elections overseen by international observers. A week later, following a dramatic increase in violence, the League suspended its observer mission.

The League sought the support of the UN Security Council for its Syrian reform plan, rejected by Damascus on the grounds that it would infringe on national sovereignty. But a UN resolution supporting the plan was vetoed by Russia, which has significant economic and military ties with Syria, and by China. It was their second veto on Security Council action. Moscow has expressed concern that it would pave the way for military intervention.

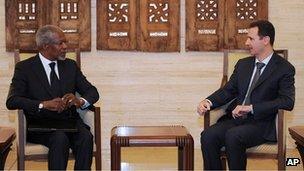

The UN and Arab League dispatched a special envoy, Kofi Annan, to Syria in March

In March 2012, after a nearly month-long bombardment of Homs by government forces that left an estimated 700 people dead and outraged many in the international community, the UN and Arab League dispatched a special envoy, former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, to Syria. He proposed to President Assad a six-point peace plan that called for a UN-supervised ceasefire by all parties, a political process to address the "aspirations" of the Syrian people, the release of detainees, delivery of aid, free movement for journalists, and the right to protest.

On 27 March 2012, Mr Annan said the Syrian government had agreed to accept the peace plan. Six days later, he told the UN Security Council that President Assad had committed to withdraw his security forces from populated areas by 10 April, with a general ceasefire within 48 hours contingent on that withdrawal. Though deeply sceptical, Western and Arab nations gave their backing to the initiative, while the opposition warned that it was likely a tactic by the Syrian government to prolong the crackdown on dissent. As the ceasefire deadline approached, the violence continued unabated, with hundreds of people being killed in army assaults on opposition strongholds and clashes with rebels.

Then on 8 April, the Syrian foreign ministry announced that the army would not withdraw until "armed terrorist groups" had presented written guarantees of a "halt to all violence". The rebel Free Syrian Army rejected the demand, saying its fighters did not recognise the government and would "not give guarantees" to lay down their arms.

Is this a sectarian conflict?

Syria is a country of 21 million people with a large Sunni majority (74%) and significant minorities (10% each) of Christians and Alawites - the Shia sect to which Mr Assad belongs. For years, Mr Assad has promoted a secular identity for the Syrian state, hoping to unify diverse communities in a region where sectarian conflict is rife - as seen in neighbouring Lebanon and Iraq.

The regime can still mobilise support, especially from minority groups and the upper classes

However, he also concentrated power in the hands of his family and members of the Alawite community, who wield a disproportionate power in the Syrian government, military and business elite. Claims of corruption and nepotism have been rife among the excluded Sunni majority. And protests have generally been biggest in Sunni-dominated rural areas, towns and cities, as opposed to mixed areas.

Opposition figures have stressed that they seek a "multi-national, multi-ethnic and religiously tolerant society". But there are fears of chaos and instability - even talk of civil war - if Mr Assad should fall. Activists say these fears are overblown.

What is the economic fallout of the unrest in Syria?

In June 2011, President Assad warned Syrians that "the most dangerous thing" facing their country was "the weakness or collapse" of its economy. Even before the unrest, Syrians had endured decades of high unemployment, widespread poverty and rising food prices.

Now, business, farming and trade have been hard hit by economic sanctions imposed by the Arab League, the European Union, the United States and neighbouring Turkey. Syria's two most vital sectors - tourism and oil - have ground to a halt. The IMF says Syria's economy contracted by 2% in 2011, while the value of the Syrian pound has crashed to its lowest level in black-market trading. Even on the official exchange rates, the Syrian pound has plummeted by more than 60% against the dollar. Inflation is also increasing rapidly, with the official rate up to 11% in March 2012. Unemployment is estimated to have risen to more than 20% since the uprising began.

In February 2012, the government doubled customs duties, which analysts said would lead to smuggling and price rises. Towns and cities, including the capital Damascus, are suffering electricity cuts, and critical products like heating oil and staples like milk powder are scarce.