Homs: Syrian revolution's fallen 'capital'

- Published

Homs, Syria's third largest city, has been a key battleground in the uprising against Bashar al-Assad.

It was dubbed the "capital of the revolution" after residents embraced the call to overthrow the president in early 2011 and much of the city fell under the control of the opposition.

But government forces launched a campaign to retake the opposition strongholds, laying siege to districts once home to tens of thousands of people.

In late 2015, rebels began evacuating the last district they held, returning the city to government hands.

Trading post

Homs has long been of geographic, strategic and economic importance.

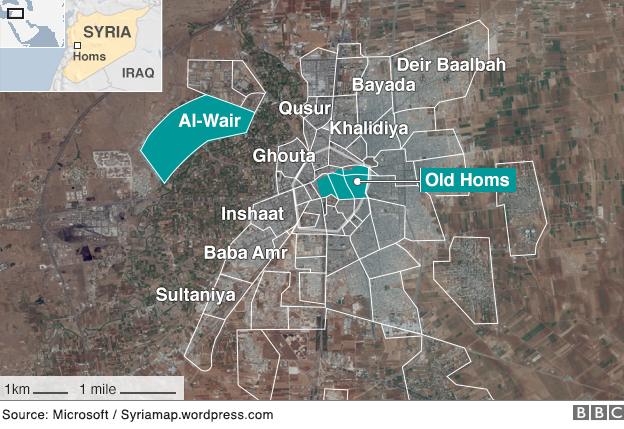

It is situated at the centre of a fertile agricultural region along the Orontes river valley at the eastern end of the Homs Gap - the only natural gateway from Syria's Mediterranean coast to the interior. It is also roughly halfway between Damascus and Aleppo, and close to Lebanon.

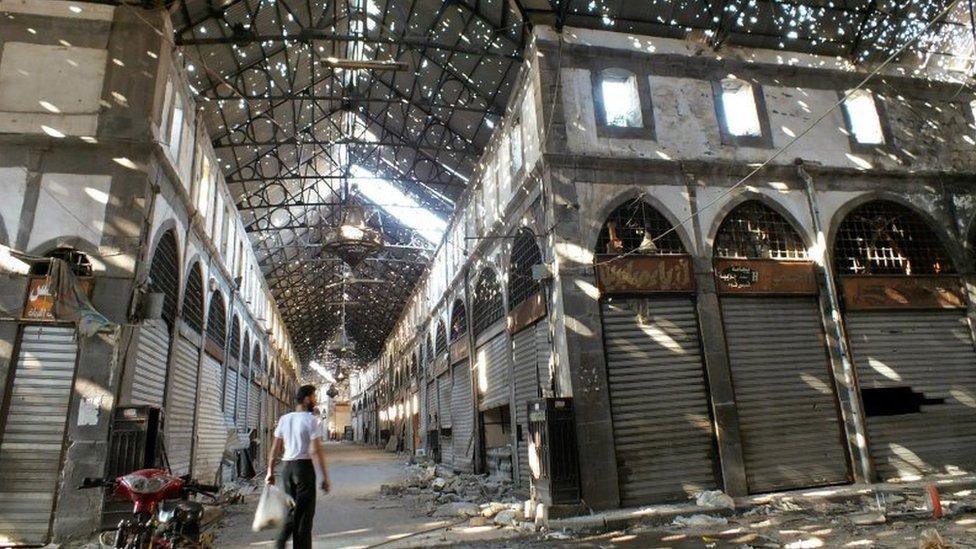

The history of Homs stretches back to the 1st Millennium BC. But it only gained importance during the Roman era, when it was known as Emesa and gave birth to a dynasty of emperors. It served as an important trading post on the route from the Mediterranean to India and China.

Under the Byzantines, the city became a centre of Christianity, and still has a large Christian population. It remained an important settlement after being taken in 636 by an Arab Muslim army led by the famous general Khalid ibn al-Walid, who is buried in its main mosque.

Today, Homs is one of Syria's most important industrial centres, boasting the country's largest oil refinery. It also sits at the hub of an important road and rail network that links Syria's main towns and cities.

Before the uprising, the population of Homs and its surroundings were estimated at 1.5 million.

Most of the inhabitants were Sunni Muslims, who lived mostly in western, northern and eastern districts. About 10% were Christians, who occupied much of the Old City, and some 25% were members of the president's Alawite sect, concentrated in south-eastern areas.

Under siege

Anti-government protests erupted in Homs within weeks of them beginning in the southern city of Deraa in mid-March 2011.

By the end of April, thousands of Homs residents were taking part in demonstrations despite a brutal crackdown by security forces and pro-Assad militiamen that left dozens dead.

Homs saw widespread protests at the start of the uprising, unlike Damascus and Aleppo

"[Homs] is one place where the people just don't give up. It has become so symbolic," Rime Allaf, an associate fellow at Chatham House, told the BBC in 2012. "People came with tents and sandwiches, prepared to face tear gas, and they were cut down with bullets."

In May 2011, tanks were sent to the city to suppress the dissent.

Opposition supporters in Homs began to take up arms, first to defend themselves and then to attack loyalist forces. There were fierce street battles as newly-formed rebel brigades gradually ousted security personnel from several districts, notably the tightly knit conservative south-western area of Baba Amr.

On 4 February 2012, the Syrian military launched an operation designed to crush the resistance in Homs. Baba Amr was subjected to a month of relentless bombardment by heavy weapons that left it destroyed and deserted.

An estimated 700 people were killed as civilians bore the brunt of the assault before the rebels staged what they called a "tactical withdrawal". Although the government insisted it was targeting only "armed terrorist gangs", indiscriminate shelling and sniper fire caused most of the casualties.

Hundreds of people were killed in Homs during a government offensive in early 2012

On 21 February, Sunday Times journalist Marie Colvin spoke to the BBC of "shelling with impunity, with merciless disregard for civilians". A day later, she and French photographer Remi Ochlik were killed in an attack on a makeshift media centre.

Thousands of civilians were also trapped without basic supplies, running water and electricity.

The offensive on Baba Amr outraged many in the international community and prompted the UN and Arab League to dispatch a special envoy to Syria. Kofi Annan proposed a six-point peace plan that included ceasefire, but the initiative ultimately failed.

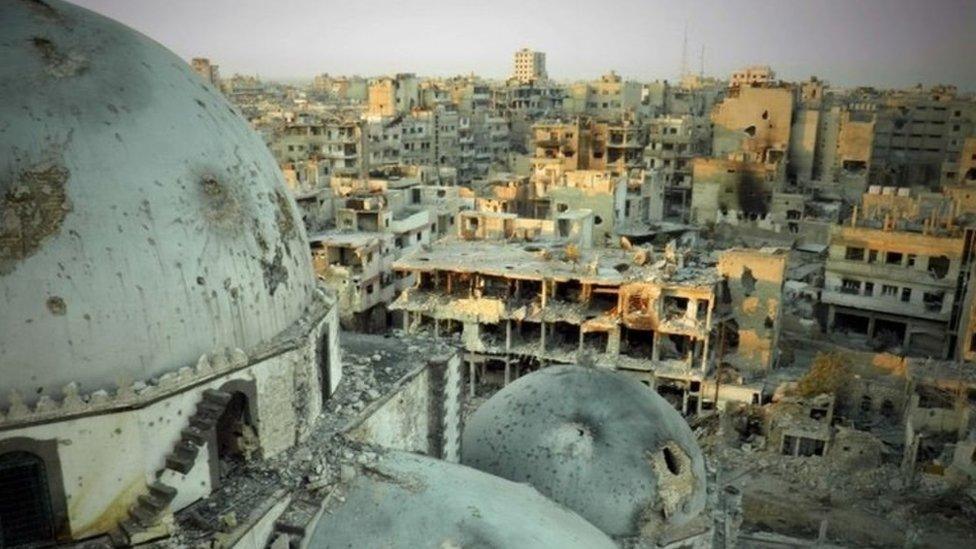

By May 2012, between 15% and 20% of Homs was believed to be under opposition control, including the Old City and the districts of Deir Baalbah and Khalidiya to the north. The next month, government forces began to besiege them, and by December 2012 they had captured Deir Baalbah.

Government forces retook the rebel-held district of Khalidiya in July 2013

In March 2013, the government launched a major offensive that it hoped would allow it to consolidate its control of Homs. Despite intense shelling, the rebels were able to repel the troops after reinforcements arrived from nearby Qusair, a strategically important town that the rebels had used to funnel weapons and fighters from Lebanon to Homs and other battlefronts.

There was a stalemate in Homs until mid-2013, when fighters from the Lebanese Shia Islamist movement Hezbollah arrived to bolster pro-Assad forces.

After capturing Qusair that June, the military swiftly launched a fresh assault on Khalidiya. Despite coming under heavy bombardment and being cut off from new supplies and reinforcements, rebel fighters in the district lasted until the end of July before being forced to withdraw.

Starvation

By the end of January 2014, the Old City was still being held by the opposition. Up to 3,000 civilians were believed to have been trapped there, without access to food and medical supplies and under repeated bombardment by artillery and aircraft, since June 2012.

The Old City of Homs was under siege between 2012 and 2014

One activist in the city told the BBC there was widespread starvation.

"There is no food. The last week we lost two innocent people," he said. "We have many casualties, many people who are diseased because of the lack of food."

Resident Baibars Altalawy said people were "eating anything that comes out of the ground, plants, even grass".

He added: "Many have died because we don't have the equipment or medicines to save their lives. What little medicine we have has expired, but we have to use it."

"We are on the edge of death, and there is no way to get the injured or sick out. And anyone who tries to escape the siege, we know that he will be killed for sure."

The government offered to allow children and women to leave besieged areas of Homs

Then, during face-to-face negotiations with the opposition at the failed Geneva II peace talks, the government announced that it would allow "innocent civilians" out of besieged areas of Homs.

Opposition representatives initially dismissed the move as a ruse to force people to leave.

However, a deal was reached in February 2014 between the Governor of Homs, Talal al-Barazi, and the UN resident co-ordinator in Syria, Yacoub El Hillo, that saw a temporary ceasefire declared, allowing the evacuation of non-combatants.

The government also allowed some deliveries of humanitarian aid to those who chose to remain.

The UN and Red Crescent were able to evacuate some 1,400 people before the truce came to an end. But about 400 boys and men aged 15 to 55 were detained by the authorities for investigation upon arrival, prompting concern for their welfare.

About 100 of them reportedly remained in detention by early April, when they were joined by another 400 men - mainly rebel fighters and draft-evaders - who the UN said had surrendered spontaneously, without negotiations and without a ceasefire.

Rebels agreed to withdraw from central Homs after failing to break the government's siege

The next month, the battle for Homs appeared to be over when rebel fighters agreed to withdraw from the last opposition-held areas in the Old City under a deal, which was brokered by the UN over several months.

"The rest of the world failed us," one activist told the BBC as he prepared for the evacuation.

The armed groups within the Old City were reportedly deeply divided about whether to accept the deal. The al-Qaeda affiliated al-Nusra Front failed in its attempt to break the siege with a series of suicide bombings.

Finally, in December 2015, in a similar deal to the one negotiated over the Old City, rebels began evacuating the western suburb al-Wair, the last area they held.