Syria: The view from next door

- Published

As Syria faces growing economic sanctions, diplomatic isolation and condemnation over what the United Nations calls "gross human rights violations" for its crackdown on protesters, the BBC's Jim Muir considers how the country's immediate neighbours are reacting and how the outcome to the crisis may affect them.

LEBANON

Nobody is watching events in Syria more closely than the Lebanese, because none of Syria's other neighbours stands to be affected as profoundly as Lebanon by what turn the crisis takes.

Syria occupied Lebanon militarily from 1976 until 2005, when it withdrew its troops under international and local pressure following the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

Despite the withdrawal, Syria remains the determining influence in Lebanese politics, and has staged a strong political comeback through its local allies, notably the two main Shia movements - Hezbollah and Amal - and their network of Lebanese partners in different communities.

Attitudes to Syria - friendship or hostility - divide the Lebanese more than any other issue. The Sunni-based alliance known as March 14, headed by Rafik Hariri's son Saad, is fiercely opposed. Its rivals, the Shia-dominated March 8 coalition headed by Hezbollah, are strongly allied to Damascus.

March 14 has clearly been delighted by President Bashar al-Assad's discomfiture, and has even been accused of smuggling arms and money across the border from Sunni areas to fuel the uprising.

Hezbollah and its allies have been dismayed in equal measure. If the Syrian regime, based on the Shia-offshoot Alawite minority, were to collapse and the Sunni majority take over, Hezbollah's lifeline from its Iranian patrons would risk being severed, leaving the movement weakened both in the Lebanese political arena and militarily vis-a-vis Israel.

Either outcome in Syria - survival or downfall of the regime - raises a clear potential for violent repercussions in Lebanon as the fortunes of local actors rise or drop.

The sectarian fault lines that connect in Syria run sharply through Lebanon, and there have already been tensions between pro-regime Alawites and hostile Sunnis in the north of the country.

TURKEY

The crisis in Syria presents its powerful, non-Arab northern neighbour Turkey with both risks and opportunities.

When the uprising broke out in March, relations between Ankara and Damascus were excellent. Mr Assad had a strong rapport with Turkey's moderate Islamist Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who threw himself immediately into trying to encourage a peaceful outcome.

But repeated interventions with Mr Assad drew a blank, leaving the Turkish leadership disillusioned and angrily accusing the Syrians of breaking promises.

Thereafter, Ankara became convinced that the downfall of Syria's Baathist regime was only a matter of time, and that the sooner it happened, the better.

Unusually, Turkey began allowing the Syrian opposition to meet and make declarations on Turkish soil, and gave sanctuary to refugees and military deserters. It has become increasingly tough on the Syrian regime, and even became involved in the Arab League sanctions meetings.

The bottom-line risks underlying Turkey's reaction are clear. Instability on its southern border is anathema. It could face big waves of refugees, as happened with Iraq in the early 1990s.

Turkey is vulnerable to the manipulation of its large Kurdish minority, and there were official suspicions that Syria may have had a hand in encouraging recent attacks by the militant PKK.

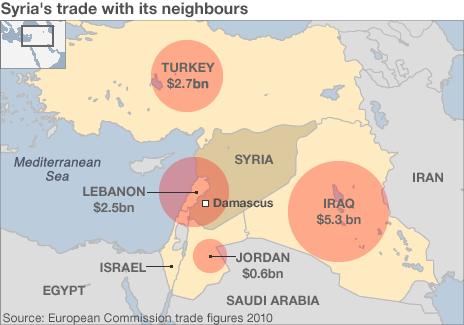

Instability in Syria also threatens vital trade routes linking Turkey to lucrative Arab markets.

But the pro-active role now played by Turkey goes beyond defence of its interests to a more ambitious pursuit of opportunities.

Regime change in Damascus in favour of the Sunni majority would deal a severe blow to Syria's strategic ally Iran, Turkey's main competitor for regional influence.

It would create a vertical Sunni axis to break the Shia crescent that links Iran, Iraq in its post-2003 Shia-majority form, Alawite-ruled Syria, and Hezbollah-dominated Lebanon.

IRAQ

Like Lebanon, Iraq has found it hard to take a coherent and unified national position on Syria because of its own internal divisions.

The Shia-dominated government led by Nouri Maliki has been generally supportive of Mr Assad - although barely two years ago relations were at rock bottom, with Baghdad accusing Damascus of harbouring Iraqi Baathists and sponsoring bomb explosions in the Iraqi capital.

Regime change in Damascus would clearly not serve the interests of the Shia majority political forces in Iraq, which are influenced to greater or lesser degree by Iran.

Reports that militant Shia leader Moqtada Sadr has been sending fighters to help Mr Assad combat the uprising have been denied, but were nonetheless politically indicative.

Were the Sunni majority to be empowered in Syria, that would give a boost to the Sunnis in Iraq, politically dominant under Saddam Hussein but now reduced to a largely disgruntled minority.

Iraqi Sunni leaders have been taking a much less sympathetic line towards Mr Assad and his regime than their Shia counterparts.

The western areas of Iraq adjacent to Syria are largely Sunni, with tribal ties spreading over the border into areas like al-Bukamal and Deir ez-Zor where there has been serious unrest - and suspicions of cross-border support.

If the Sunni majority took over in Syria, that could bolster Iraqi Sunni sentiment in the western al-Anbar province and elsewhere, where some Sunnis are starting to push for the kind of federal autonomy enjoyed by Iraqi Kurds in the north.

Iraq's Kurdish areas also abut Kurdish-populated parts of north-east Syria.

So a scenario in which Syria disintegrated into civil and ethnic strife could see stronger cross-border ties emerging between the Kurds, strengthening their aspirations for nationhood.

JORDAN

Like a spouse trapped in an unhappy but inescapable marriage, Jordan's relationship with its powerful northern neighbour has fluctuated sharply over the years, ranging between extreme tension and cautious cordiality.

They are bound together by many neighbourly bonds that make Jordan extremely sensitive to change and instability in Syria.

Syria controls the headwaters of the River Jordan on which the kingdom depends for much of its water supply.

It also straddles the overland route vital to Jordan's trade.

Hundreds of Jordanian students are placed in Syrian universities, and there are strong tribal and family ties that cross the borders.

But politically the two countries are chalk and cheese.

Jordan is firmly in the pro-Western camp and in 1994 became the second Arab country, after Egypt, to sign a peace agreement with Israel, leaving Syria more isolated in its efforts to regain the occupied Golan Heights.

Jordan is also a basically Sunni country, while Syria's Sunni majority is ruled by a regime dominated by its Alawite minority. At times of tension in the past, Syria has accused Jordan (where there are pockets of Islamist militancy in the north) of stirring unrest among the Sunnis.

Because of all these sensitivities and vulnerabilities, Jordan has been very low-key in its reaction to the crisis in Syria - which began in Deraa, a southern city with strong tribal and family ties across the nearby Jordanian border.

Jordanian officials recently admitted that some arms and ammunition had been making their way across the border, though they said they were trying to stop it.

The official policy is non-interference, and even strong criticism has been couched as advice rather than intervention.

When King Abdullah suggested in November that Mr Assad should step down, he was careful to say that that was what he would do in his position, rather than calling on him to do so.

ISRAEL

As a country which has fought two wars with Syria and continues to occupy part of its territory, Israel clearly has an enormous stake in the outcome of the Syrian crisis.

But where Israel's national interest lies is far from clear, and its leaders have been very circumspect in commenting on Syrian developments.

Despite the Assad regime's much-vaunted "resistance" to Israel, its sponsorship of militant groups such as Hezbollah and Hamas, and its alliance with Iran, Israeli leaders have been divided over whether the survival of the "devil they know" would be preferable to the uncertainties of regime change and the possibility, however remote, of a radical Islamist takeover.

In practice, despite the fact that there is no peace treaty between the two countries, Israel's front line with Syria on the Golan plateau has been peaceful since a truce was concluded in 1974 - with the exception of two incidents earlier this year when the Syrians, perhaps hoping to distract attention from the internal turmoil, allowed Palestinian demonstrators to approach the front.

Under the Assad family, Syria has engaged in peace dialogue with Israel - most recently through Turkish intermediaries two years ago - but even the failure of those initiatives did not lead to trouble.

So in some ways, Israelis might see their favoured scenario as the survival of a regime which has proven containable, even though in 2007 Israel carried out an air strike on what it believed to be a nascent nuclear plant near Deir ez-Zor.

But ideally from Israel's standpoint, the regime would emerge weakened to the point of having to drop its alliances with Iran, Hezbollah and Hamas.

However, events may already have gone too far for that, and some Israeli leaders have concluded that the regime is likely to fall in months, opening a wide range of possible scenarios.

Ironically, Israel's proximity and the sensitivities it arouses are the strongest deterrent to Libya-style Western intervention in Syria.