Iran and UK - centuries of mistrust

- Published

Iran has apologised for Tuesday's attacks on the UK compounds in Tehran

Asked to conjure up an image of the relationship between Iran and the UK in recent decades, then perhaps - unfortunately - protesters burning and stamping on flags in Tehran might be it.

Tuesday's attack was not an unfamiliar sight, with the embassy being a common site of protest for conservative Iranians denouncing British policy.

It has since led to the closure of the embassy in London and the expulsion of Iranian diplomats.

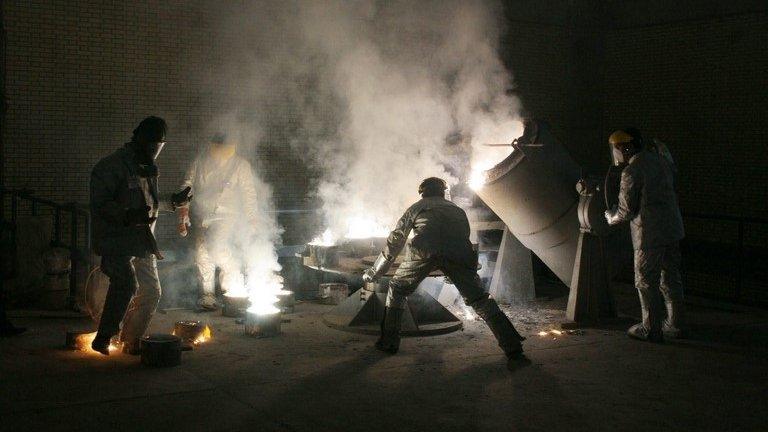

The latest incident came amid mounting tensions over Iran's nuclear programme, which the West believes is part of efforts to make a nuclear weapon - a claim fiercely denied by Tehran.

The UK was one of three countries who last week ratcheted up sanctions against Iran, cutting all ties with the country's financial sector.

But the anger expressed reflects a wider animosity held by the Islamist state, and exposes the rocky history between the two nations.

Lawmakers in parliament on Sunday were quoted as chanting "Death to England".

And Iran's speaker of parliament, Ali Larijani, said the incident was the outcome of "decades of domineering moves by the British in Iran".

'Humiliating deal'

Relations between the two countries have been particularly turbulent since the Iranian revolution in 1979, but the animosity has a history of centuries, not decades.

Britain has ordered the immediate closure of the Iranian embassy in London

In the 19th Century, following the first Russo-Persian war, Iran was forced to concede territory under what was regarded as a humiliating deal for the nation.

The 1813 accord was put together by a Briton - diplomat Sir Gore Ouseley - casting an early shadow over British and Iranian relations.

Less than half a century later, the two countries were at war after the UK opposed Iran's attempts to retake Herat (in present-day Afghanistan).

Iran lost its claim, and in the 1860s the British again drew the lines of Iranian territory when it helped set its borders with India.

Meanwhile, it was British forces in Iran under Gen Edmund Ironside in the 1920s who helped put Reza Shah on the throne.

His son was Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the shah later ousted during Iran's revolution.

Mossadegh coup

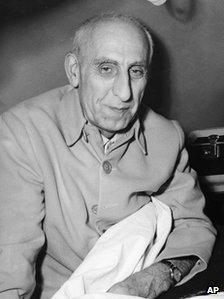

In modern times, one event is seen as particularly pivotal to how Iranians view Britain: the overthrow of Mohammed Mossadegh in 1953.

Mossadegh was overthrown in a coup backed by Britain and the US

Mossadegh, who was elected prime minister in 1951 after the assassination of Gen Ali Razamara, had wanted to nationalise the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company in which the British had a majority share.

The British sought the help of the Americans and organised a coup; Mossadegh was placed under house arrest.

Pahlavi was restored to power as shah, ruling autocratically until he himself was removed in 1979 in the Islamic Revolution.

In the years that followed, Islamic revolutionaries directed their ire on the US - "the Great Satan" - with the US hostage crisis in 1979-1980 plunging relations to new depths.

Iran also resented the support that Western countries gave Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war. This boiled over in 1987, when members of the Revolutionary Guards abducted and beat up the British charge d'affaires, Edward Chaplin.

The downing of an Iranian passenger jet by the US in 1988 - with the deaths of all 290 people aboard - further complicated the situation.

Nuclear issue

In 1988, the British embassy in Tehran re-opened, eight years after it was closed. A year later, Iran issued a fatwa against British author Salman Rushdie for his controversial novel The Satanic Verses.

In recent years, the two nations have for the most part managed to maintain diplomatic relations.

Iran accused Britain of involvement in the post-presidential election unrest in Iran in 2009

There were signs of improvement in 1999, when the UK and Iran exchanged ambassadors for the first time since the revolution, and again two years later when Foreign Secretary Jack Straw visited Tehran - the first of several such trips.

But that cold peace is punctured by various upsets.

In one incident in 2007, Iran detained 15 British sailors and marines in disputed waters along the Iraqi border, keeping them for two weeks before releasing them as a good-will gesture.

Two years later, Iran denounced Britain for supporting widespread demonstrations organised by the opposition against President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

Both countries continue to remain at odds over the nuclear issue and human rights, issues unlikely to be settled any time soon.

How both countries react to the latest incident - and to the wider nuclear issue - may set the temperature for how Iran sees Britain in the future.

But it is likely that a climate of simmering mistrust will remain for some years to come.

- Published30 November 2011

- Published20 August 2015

- Published29 November 2011

- Published25 November 2014