Iran nuclear programme: Why sanctions are faltering

- Published

The latest Western sanctions, prompted by a report by the UN's nuclear watchdog, caused anger in Iran

The storming of the British embassy compound in Tehran is claimed by demonstrators to be a response to Britain's prominent part in applying ever tougher economic sanctions against Iran.

There may be a good deal of domestic Iranian politics involved too: power struggles within Iran's conservative ruling elite may offer a partial explanation for the upsurge in tensions.

But there is no doubt that Britain has been an active player in trying to bring ever-increasing economic pressure on Tehran.

The most recent report from the International Atomic Energy Agency, published earlier this month, was taken by Western capitals as painting a worrying picture about a possible military dimension to Iran's nuclear activities.

Much of the material in the IAEA report was not new but, marshalled together, it did suggest that there were many areas where Iran still needed to provide reassurance and explanation about what it was doing.

Financial target

The IAEA report prompted new Western sanctions against Iran which on the face of things significantly toughened the economic climate in which Tehran must operate.

In Britain, the government imposed new financial restrictions severing all ties with Iranian banks. This was the first time that a country's entire banking sector was cut off from British financial institutions.

In the US, the Obama administration designated Iran as "a primary money laundering concern".

Here again, the goal was to hit Iran's financial sector - the US and UK efforts all aimed to make it much harder for Iran to conduct its business abroad.

A range of other measures were taken by the Americans, and Canada and France also stepped up their sanctions against Tehran.

Patchy picture

Of course these steps were all bilateral in nature. The new IAEA report did not impress the Chinese or the Russians who were unwilling to allow it to prompt a new round of UN sanctions.

This is one of the central problems with the Iran sanctions regime. It is really several regimes, applied to varying degrees by different countries. Even existing multilateral UN-backed sanctions are applied differently by different governments.

The sum total is that it is indeed harder for the Iranians to do business. But their growing reliance on China as a trading partner - its role in the Iranian economy is growing markedly - means that innovative ways can be found to get around financial sanctions.

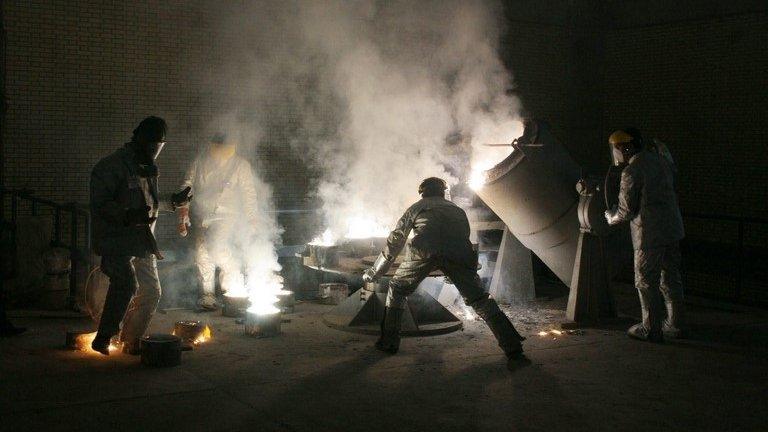

Iran says it has a right to develop nuclear energy

If there are problems arranging foreign payments for imports or exports, especially in dollars, then barter deals can be struck which remove these trades from the international financial system altogether.

We are back in many ways to the perennial debates about economic sanctions.

Do they work? Over what period must they be applied? And what is their goal? Are they there to isolate, to contain, or to coerce?

Western leaders insist that sanctions essentially have two purposes.

One is to constrain Iran's nuclear activities themselves by restricting the country's access to advanced tooling, crucial materials and so on.

Second, by applying pressure to individuals and key sectors of the economy - "targeted sanctions", in the jargon - the hope is to persuade the Iranians back to the negotiating table.

All the indications, though, are that this approach is only partially working.

It is hard to say how far Iran's nuclear activities are being constrained. It is, according to the IAEA and Western diplomats, making slow steady progress on a number of fronts.

How far the pace of its research effort is dictated by sanctions, how much it is hindered by sabotage efforts from outside, and how much its pace is a function of the Iranian political leadership's agenda are all unclear.

Joint effort

But in terms of its coercive effect in bringing Iran back to the negotiating table the sanctions regime seems much less successful.

That is why, perhaps, while backing tougher measures, the Obama administration has sought to keep Russia and China on board.

Neither Moscow nor Beijing want to see a nuclear-armed Iran.

For now there is utility in having all of the major powers singing from at least part of the same song-sheet.

But the international coalition against Iran is looking more and more divided.

As US and Russian presidential elections loom, and with unease growing in Israel and uncertainty throughout much of the wider Middle East, the almost predictable round of IAEA reports, tougher sanctions and then calls for more of the same, may be coming to an end.

- Published30 November 2011

- Published25 November 2014