Egypt's revolution: 18 days in Tahrir Square

- Published

During the 18 days of protests, the final outcome was far from inevitable

The three years that I spent working in Egypt turned out to be the last in President Hosni Mubarak's three decades in power.

Yet for most of my time here, I would have predicted a very different exit for him than the dramatic events of the 25 January revolution.

Having reported on poverty, youth unemployment, corruption and torture, I was in no doubt that Egyptians had deep grievances.

Yet I found it hard to believe in people power. I had witnessed successive anti-government protests, where the brutal security forces massively outnumbered the few dozen activists on the streets.

It was Tunisia that provided a new model. President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali fled his country last year on 14 January following a popular revolt.

Just over a week later, some 90,000 Egyptians had pledged support on Facebook for their own "Day of Rage", coinciding with National Police Day.

Ordinary Egyptians voiced their anger in a way that they had never heard before

For once an online invitation was answered by real cries of protest. Surprisingly large crowds turned out not just in Cairo, but in Alexandria, Suez and Ismailia not just in Cairo but in Alexandria, Suez and Ismailia.

By 28 January, when I was choking on tear gas on the back streets of Cairo's Giza district, I finally concluded that Egypt had changed.

Ordinary Egyptians were voicing their anger in a way that I had not heard before.

"We are so furious. We must have change, better chances to work, to buy a flat and have just the life's basics," one man told me.

"What happened in Tunisia has knocked some sense into people."

Martyrs and mobilisation

I saw blood and injuries that day but no bodies. With the internet and mobile-phone lines down, it took a while to find out about the first "martyrs" of Egypt's revolution.

Later, Ehab el-Sawy showed me disturbing mobile phone footage of the corpse of his brother, Mustafa, in the morgue. The 25-year-old was shot in the neck and chest on Cairo's Qasr al-Aini Bridge.

"We saw police officers with dead consciences. They fired on people without a brick in their hands," Ehab said.

Friends of Ahmed Bassiouni put up a poster of him in remembrance during the revolution

Outside the Hardee's restaurant in Tahrir Square, I came across a university art lecturer, Shady Noshokaty, whose friend and colleague, Ahmed Bassiouni, had also been shot dead.

He was hanging up a smiling poster of the dead man, whom he wanted to be remembered as "a brave, honest, crazy, beloved guy".

Shady was determined his friend would not die in vain.

"I'll be honest, in the beginning I wasn't sure the demonstration would do anything, but now it's really become my cause," he said.

During the 18 days of protests that eventually forced Mr Mubarak from office, the final outcome was far from inevitable.

There were many iconic moments that suggested the protesters had the upper hand: the , external; Mr Mubarak's , external; and the emotional release of one of the revolution's planners, Wael Ghonim of Google, on 7 February after 12 days in detention.

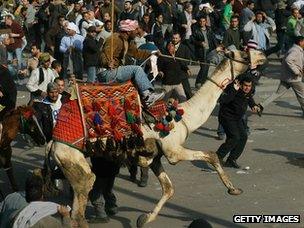

A Mubarak supporter and his camel scattered the crowd in Tahrir Square on one day

But there were also dark days, like the surreal "battle of the camel".

After several pro-Mubarak rallies took place around Cairo, tough-looking men headed for Tahrir Square on 2 February - some on horseback and one on a camel - and launched another deadly attack.

Short-lived euphoria

It was hard not to get swept up in the huge victory party that took over central Cairo on 11 February after state television announced that the president was stepping down.

Yet even at the time, some of the jubilant cries seemed rather naive.

I heard shouts of "this is freedom" and "it's over - the people have won".

As the military council took control, soldiers were hailed as heroes.

"Of course, absolute power corrupts," says Amr Gharbeia, one of the bloggers who camped out in Tahrir Square, looking back. "The only thing that could keep it in check was people on the street."

Young activists turned Tahrir Square into a carnival of freedom

Last July, Amr was beaten and held for a night by military police in Cairo after a march against the armed forces.

He describes how the deterioration in activists' relations with the military soon became "more personal and close".

Another online activist, Malek Mustafa, was shot in the eye during protests demanding a faster transfer to civilian rule in November.

Blogger Nawara Negm was attacked by a mob that accused her of stirring up strife with the army

This month, blogger Nawara Negm, who I first encountered during a cheery Tahrir campsite sing-along, was attacked by a mob that accused her of stirring up strife with the army.

Many of my friends in Egypt have also been caught up in waves of violence during this tumultuous year. Two news photographers were injured, one in the head, when police fired buckshot at protesters.

Others have fallen victim to the increased crime.

Long troubled by rising sectarian tensions, my Arabic teacher, a Coptic Christian, decided to move abroad.

Islamist gains

The real winners of the 25 January revolution have undoubtedly been the Islamists.

Within the past year, the mainstream Muslim Brotherhood has gone from being a banned group to setting up its own Freedom and Justice Party, which won 47% of seats in the newly elected People's Assembly.

The first time I interviewed Sondos Asem, external, a Brotherhood activist in her early 20s, was shortly after I arrived in Egypt. We agreed that I would not publish her real name because of fears for her safety.

We joked about this when we met for coffee after the revolution.

"From now on I will always be Sondos," she grinned.

When we saw each other again - during the election process - she was busy helping to run the Brotherhood's English-language Twitter feed, external.

The Muslim Brotherhood dominates the newly-elected People's Assembly

She downplayed the influence that more fundamentalist Salafists might have on her group's political agenda.

"The Brotherhood has been moderated by its past experience in parliament," she said. "We hope this will happen to [the main Salafist] Nour party too."

Nour went on to win nearly a quarter of the seats in parliament.

On Wednesday, Sondos plans to join a rally to Tahrir Square, "same as last year", to keep up pressure on the ruling military to hand over power.

Despite heavy rain, many activists returned to their tents in the square on Tuesday night. They see themselves as custodians of the revolution.

"I feel very worried. There's a lot of uncertainty because a lot of our goals have not yet been met," says prominent Egyptian journalist Shahira Amin, who has been among the crowds.

"But I still feel the energy is here and the trend is irreversible."