Yemen's new president faces multiple challenges

- Published

One of the new Yemeni president's top priorities is reducing rural poverty

For the last few days in Yemen's capital, Sanaa, they have been holding marches and rallies to whip up enthusiasm for Tuesday's presidential election.

I went to one on Monday morning in the Sanaa football stadium.

Tens of thousands of enthusiastic young men and women waved Yemeni flags and held up posters of the Vice-President, Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi.

Dressed in traditional turbans and robes, huge daggers stuck into their belts, men danced to the beat of a large drum.

"Welcome, welcome," shouted virtually anyone who noticed the foreigner pushing through the crowd.

Now all this excitement for Yemen's election can seem to an outsider rather peculiar.

New dawn

Vice-President Hadi is the only candidate. But that, I am told, is to miss the point.

One enthusiastic young man came up to me and shook my hand vigorously.

"For many people like me it's the first time they will wake up in the morning to find there is a new president," he told me, "and a president who isn't the son or nephew of old the president."

And this is the real point.

For last 33 years Yemen has been ruled by one man - Ali Abdullah Saleh.

Given that most Yemenis are under 25, that means Mr Saleh is the only president any of them have ever known. And they are desperate to see the back of him.

On Tuesday night they will get their wish.

But while Yemen will get rid of President Saleh, there is still a big question about the rest of his family.

Mr Saleh ran the country much like a family firm - his brother runs the air force, his son the Republican Guard, one of his nephews the presidential guard, and another nephew the internal security service and counter-terrorism unit.

'We'll stay'

I went to see the last of those at its plush headquarters in Sanaa.

Brigadier Yahia Saleh is in no hurry to follow his uncle and leave power

Brigadier Yahia Saleh is a jovial figure in a smart uniform and with a neatly trimmed moustache.

He is a fan of Che Guevara, and sends his senior staff to be trained at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst in the UK.

"Are you going to step down once your uncle has left power?" I asked him.

"Why would I?" he replied with a look of bewilderment on his face. "Is there a reason for us to leave?"

"Many Yemenis say all the Saleh family should step down, and that you only got your posts because of your uncle," I said.

"If we listen to opposition, half of Yemen must leave the country," Brig Saleh said with a dismissive wave of his hand.

"This won't happen. We'll stay and the new president of Yemen will appreciate people who work for the security of the country."

Militant threat

The work he is talking about is the fight against al-Qaeda.

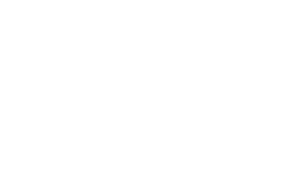

In the dusty hills outside Sanaa, I was taken by some of Brig Saleh's men to see what they do.

Yemen's security forces face multiple challenges

The soldiers are all extremely well dressed, equipped and disciplined.

As we watched, they carried out a mock house clearing operation. It was clear to see by the way they moved that they had been trained by Americans.

The rapid spread of al-Qaeda across Yemen in recent years is why the outside world cares about what happens here.

The US is spending tens, some say hundreds of millions of dollars in Yemen each year to support the fight against the Islamist militant network

There is no doubt the threat from the group's regional offshoot - al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) - is real.

In the last year, AQAP and its local allies have taken control of two districts - one in the south, around the town of Zinjibar; another south-east of Sanaa, in and around the town of Radaa.

But in Sanaa there is now a growing chorus of politicians and analysts who say the military campaign against AQAP has been a disaster.

Nadia al-Saqqaf is the editor of the English-language Yemen Times, and a star of Sanaa's intellectual community.

"Al-Qaeda is real," she told me. "We cannot just deny it, it's there."

"But Yemen is a conservative country and there are lots of people who sympathise with its religion - [especially] if al-Qaeda comes and drills a well, when the state doesn't do that for you. So al-Qaeda is giving you life and heaven."

'Huge problems'

To get an idea of what Ms Saqqaf was talking about, I took a plane west to the Red Sea coast and then drove north deep in to the Yemeni countryside.

Our 4x4 vehicle finally bumped to a halt in the dusty village of Deir Ayyash, a collection of mud-and-straw houses on a dusty plain.

Outside one of the houses, a group of women had gathered carrying young babies in their arms. The women were covered from head-to-toe in black, only their eyes peeking out at the strangers. Several of the babies were clearly very sick.

My guide was Dr Rajia Sharhan, who works for the United Nations Children's Fund (Unicef). She took the arm of one of the babies and, with a special tape, measured its upper arm.

"The circumference is only 10.5cm (4.1in)," she said. "That shows this baby is suffering severe acute malnutrition. If he develops a fever or diarrhoea he is in danger of dying."

"I don't think people outside Yemen realise how serious the situation is," I told her.

"The situation in Yemen is very serious," Dr Sharhan replied. "Half a million children are at risk of dying or developing disability - if they live."

Yemen is the poorest country in the Arabian Peninsula

"We are shocked by results of our survey and trying our best to raise our voice that there is a huge problem in Yemen. If not addressed now, we will regret it later."

For years President Saleh has done nothing for people in villages like Deir Ayyash, while building up his army to suppress rebellions and fight al-Qaeda.

There are no paved roads in Deir Ayyash, no running water, no electricity. The local clinic only has any medicines because Unicef brings them here.

If, as many here say, it is poverty not ideology that is driving Yemenis in to the arms of al-Qaeda, then the new president needs to start in Yemen's villages.

And none of the problems here can be solved with guns.