Egypt's police still in crisis after revolution

- Published

Egypt's central security forces continue to use tough tactics against protesters

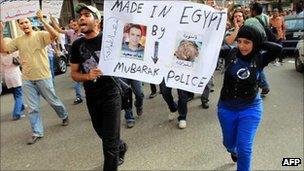

It was no coincidence that Egypt's uprising began on Police Day last year; protesters' original demands included the resignation of the hated former interior minister, Habib al-Adly, and an end to the abuses committed by his security forces.

One of the most influential Facebook groups calling for people to take to the streets was "We are all Khaled Said", set up in memory of a young man alleged to have been killed by police officers in Alexandria in 2010.

Yet to date, there have been relatively few reforms and the crisis in Egyptian policing has only deepened.

The police are less feared than before the revolution and at the same time less respected than ever. As a result, morale in the force is low. And now, Egyptians are dealing with a security vacuum.

Recently there has been a spate of serious crimes of a kind not seen in the past, including armed bank robberies and kidnappings for ransom. Petty theft has risen dramatically.

People found it easy to believe that the security forces were either negligent or directly implicated in February's football violence in Port Said that left more than 70 people dead.

In an unusually candid interview with a former senior police officer, I heard first-hand why the forces meant to protect Egyptians have become better known for corruption and brutality.

"Egyptian police ruled the country from behind an iron curtain. They controlled all aspects of life," says Mahmoud Qutri who retired as a police brigadier in 2001.

"If you wanted to be promoted in a government job then you needed approval from state security, even if you were a low-level employee."

He explains how police abused their sweeping powers in many ways.

Prior to the 2011 revolution there were protests in Egypt over the death of Khaled Said

"Much of what I saw was shocking," he says. "Police officers would bully people, torture them, 'sex-up' cases and deliberately send innocent people to jail."

Mr Qutri gives the example of a father who went to report his daughter missing only to be tortured and imprisoned himself before she returned home of her own accord.

In another case, he says, a young army conscript was jailed after being forced to confess to raping and killing a woman who later turned up unharmed.

'Routine torture'

The ex-police brigadier's descriptions of torture methods commonly used by Egyptian security services are most disturbing.

"Police can use finger prints or other technologies in criminal investigations but they don't have enough resources so they use other techniques that save time and money," Mr Qutri tells me.

"Usually they cuff your hands and put a bar under your knees and beat your feet. Sometimes they handcuff and hang you on a door until your shoulder breaks," he says.

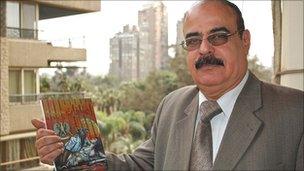

Mahmoud Qutri wrote an uncompromising account of his career - Confessions of a Police Officer

"In Bedouin areas where masculinity means a lot, I have seen men electrocuted on their genitals. They also blow air into a man's anus and jump on the stomach. In state security departments, they might bring someone's wife, sister or daughter and rape her to make him confess."

Mr Qutri says it was impossible to speak out while he was in his old job but since his retirement he has acted as a whistleblower. In 2004, he evaded censors to publish a book, Confessions of a Police Officer, which led to lawsuits and personal threats.

Only since Egypt's popular uprising has he felt freer to call for radical changes to the police system.

He complains of a culture that breeds hostility and disdain.

"The police students are taught how to be very arrogant. In the academy they are ordered to walk in a certain way, not to use public transport nor sit in cafes," he says. "By graduation they feel they are more important than ordinary people."

Radical reforms

Mr Qutri recommends new programmes that teach trainees about law and human rights as well as better pay for lower ranking police and an end to a quota system which he says, leads to the fabrication of crimes.

He argues that under the former interior minister, Habib al-Adly, state security was prioritised over public security but that this must now change.

Several draft initiatives to restructure and reform the security sector are already being submitted to parliament.

Omar Ashour of the Doha Brookings Institute and Exeter University has helped draw up one set of proposals.

"There needs to be accountability towards citizens - whether the parliament or the president - the idea of controlling the security sector has to be enshrined in the [new] constitution," says Mr Ashour.

A senior Muslim Brotherhood official, Amr Darrag, identifies security reform as the top priority for his organisation's Freedom and Justice Party - which controls nearly half the seats in the new People's Assembly.

"This is probably the most important issue that we would like to tackle because it's the key for stability and that's key for any economic development or further reform," he says.

In the past year, the ruling military has been criticised for making relatively few changes.

Riot police are accused of using brutal tactics to suppress protests after the Port Said football deaths

The only notable developments have been the disbanding of the State Security Investigations Service and putting Mr Adly on trial for corruption and giving orders that led to the killing of hundreds of demonstrators.

A new investigation into the protests that followed the Port Said deaths by the human rights group Amnesty International concluded that riot police from the central security forces used the same "excessive force" that was deployed when trying to suppress Egypt's uprising. Sixteen people were killed and hundreds injured in Cairo and Suez.

"Unless the Egyptian security apparatus is reformed with the aim of providing security and upholding the right to peaceful protest, we fear more bloodshed will follow," says Hassiba Hadj Sahraoui of Amnesty International.