Iran's opposition: Gagged by years of intimidation

- Published

Supporters of Mir Hossein Mousavi and the Green Movement demonstrated on the streets in 2009

In Iran, the what-you're-not-allowed-to-do list keeps expanding. Supporters of the opposition Green Movement are no longer allowed to demonstrate. What's more, they're not allowed even to talk about thinking of demonstrating.

In Tehran, reformists are unable to go and visit their leader Mir Hossein Mousavi, who's under house arrest. Even stopping on the street outside his house is too dangerous. A brisk walk-by is all that anyone can get away with.

A short clip posted on YouTube, external claims to show the street in which Mr Mousavi is being held under house arrest.

The video-maker walks along an empty road - trying to point the camera across the road towards black metal gates which bar the way to a smaller side street. The footage ends abruptly when a single guard suddenly comes into frame across the road.

This silent video demonstrates what's happened to the Green Movement since the disputed presidential election of 2009. The opposition protests of that summer were put down by the government. Mr Mousavi, one of the defeated presidential candidates, has been under house arrest since February 2011.

Go-betweens and emissaries

He and his wife, Zahra Rahnavard, are unable to communicate directly with the outside world. They have to pass messages via their daughters - who are allowed occasional visits and phone calls. These messages are then transmitted by pro-reformist websites, anxious to show that Mr Mousavi remains a significant force in Iranian politics.

The pro-reform website Rahesabz writes that one of sons of Iran's Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has even been to see Mr Mousavi. It says Mojtaba Khamenei, widely regarded as the Ayatollah's most trusted emissary, paid a visit to Mr Mousavi's house earlier this year.

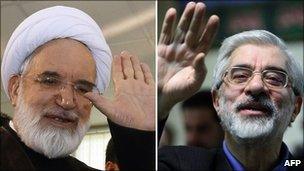

Presidential candidates Mehdi Karroubi (L) and Mr Mousavi have been under house arrest for a year

The website reports that Mojtaba Khamenei urged Mr Mousavi to compromise. In return, the opposition leader apparently asked for a direct one-to-one meeting with the Supreme Leader and the chance to speak on TV and radio.

According to the Rahesabz site, Mr Khamenei left the house "in resentment". This visit is hard to verify independently but publication of the story is a sign that the Green Movement wants to promote Mr Mousavi as a heroic figure, resisting appeals to back down.

"I am still standing on my previous position and nothing has changed," the opposition Kalemeh website quotes Mr Mousavi telling his daughters in a recent phone conversation.

Struggling to be heard

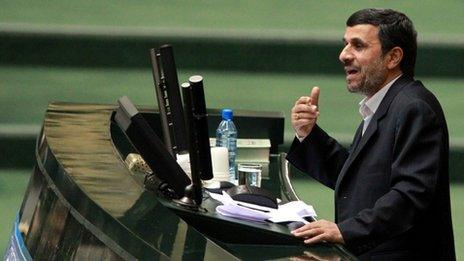

Some supporters fear that the opposition has lost its way. The loose coalition of reformists that formed the Green Movement in 2009 united around a simple desire to defeat President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But the president is still in office.

The Green Movement of 2012 struggles to define its goals. Iran's government has made it almost impossible for anyone sympathetic to the opposition to make his or her voice heard.

International human rights organisations accuse Iran of carrying out a wave of arrests in recent months against political activists, lawyers, students, journalists, bloggers, filmmakers, religious and ethnic minorities.

"Iran's multiple and often parallel security bodies - including a new cyber police force - can now scrutinise activists as they use personal computers in the privacy of their homes," writes Amnesty International in a new report, external entitled Expanding Repression of Dissent in Iran.

"They have restricted bandwidth and are developing state-run servers, specific internet protocols (IPs), internet service providers (ISPs) and search engines. Countless websites, including international and domestic social networking sites are blocked," the report continues.

These tactics have helped the government to see off recent attempts by the opposition to stage demonstrations. On 14 February, reformists called for protests to mark the anniversary of the house arrest of Mr Mousavi and his fellow Green Movement leader Mehdi Karroubi.

The government was quick to respond. It blocked access to foreign email services. The Intelligence Ministry warned known activists to stay indoors on the day of the planned protests. Uniformed and plain clothes security forces were deployed in great numbers in Tehran. The opposition was unable to demonstrate.

'Graveyard silence'

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that 10 reporters were jailed in January (in addition to the 42 journalists and bloggers whom Iran was already holding in December 2011).

"The government's intolerance of dissent is rising as parliamentary elections approach," said the CPJ's Mohamed Abdel Dayem in a statement, external. "Tehran is using the mass arrests of journalists as an intimidation tactic to silence those who dare criticise it."

The Green Movement has little choice but to try to turn that silence to its own advantage. It's asked its supporters not to take part in the forthcoming parliamentary elections on 2 March. It hopes that the silence registered by a low turnout at the ballot box will remind the country that the opposition still exists.

"Boycotting the election is a national duty," is the slogan written on posters stuck to walls and benches in the northern city of Tabriz.

"Didn't you want graveyard silence across the country?" the Co-ordination Council of Iran's Green Movement says in a statement directed towards Iran's government.

"Now the people want to demonstrate the results of this graveyard silence. In a graveyard no-one celebrates, not even for your sake. If you want to - as you put it - turn up the election heat, rig the figures as in 2009, order the state radio and TV to prepare extensive reports from provinces and show the waiting queues longer than ever... what is these people's sin if they do not want to be the fuel for your fire?"

In the 2009 presidential election, supporters of the Green Movement voted, then they protested on the streets. In the 2012 parliamentary election, the only way they can resist is to stay at home. As is the case with Mir Hossein Mousavi, their silent leader.

- Published14 February 2012

- Published7 February 2012

- Published14 October 2024