Egypt's sexual harassment of women 'epidemic'

- Published

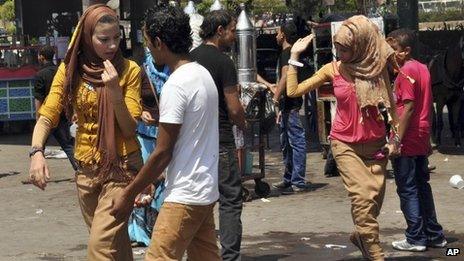

Some Egyptian women are now scared to appear alone or even with female friends in public places

Campaigners in Egypt say the problem of sexual harassment is reaching epidemic proportions, with a rise in such incidents over the past three months. For many Egyptian women, sexual harassment - which sometimes turns into violent mob-style attacks - is a daily fact of life, reports the BBC's Bethany Bell in Cairo.

Last winter, an Egyptian woman was assaulted by a crowd of men in the city of Alexandria.

In video footage of the incident, posted on the internet, she is hauled over men's shoulders and dragged along the ground, her screams barely audible over the shouts of the mob.

It is hard to tell who is attacking her and who is trying to help.

The case was one of the most extreme - but surveys say many Egyptian women face some form of sexual harassment every day.

Marwa, not her real name, says she worries about being groped or verbally harassed whenever she goes downtown. She says it makes her afraid.

"This is something that scares me, as a girl. When I want to go out, walking the street and someone harasses or annoys me, it makes me afraid.

"This stops me from going out. I try to be excessively cautious in the way I dress so I avoid wearing things that attract people."

'Deeply rooted'

The day I met Marwa, she was wearing a long headscarf pinned like a wimple under her chin, and a loose flowing dress with long sleeves over baggy trousers.

But dressing conservatively is no longer a protection, according to Dina Farid of the campaign group Egypt's Girls are a Red Line.

She says even women who wear the full-face veil - the niqab - are being targeted.

"It does not make a difference at all. Most of Egyptian ladies are veiled [with a headscarf] and most of them have experienced sexual harassment.

"Statistics say that most of the women or girls who have been sexually harassed have been veiled or completely covered up with the niqab."

Harassers are getting younger, campaigners say

In 2008, a study by the Egyptian Centre for Women's Rights found that more than 80% of Egyptian women have experienced sexual harassment, and that the majority of the victims were those who wore Islamic headscarves.

Said Sadek, a sociologist from the American University in Cairo, says that the problem is deeply rooted in Egyptian society: a mixture of what he calls increasing Islamic conservatism, on the rise since the late 1960s, and old patriarchal attitudes.

"Religious fundamentalism arose, and they began to target women. They want women to go back to the home and not work.

"Male patriarchal culture does not accept that women are higher than men, because some women had education and got to work, and some men lagged behind and so one way to equalise status is to shock women and force a sexual situation on them anywhere.

"It is not the culture of the Pharaohs; it is the culture of the Bedouins," Mr Sadek says.

Mr Sadek and women's campaign groups also blame what they call the lack of security enforcement. They say the police should do more to enforce laws protecting women from harassment.

'Provocative dress'

And the harassers are getting younger and younger.

On the Qasr al-Nil bridge in central Cairo, a hotspot for harassment, I met a group of teenage boys hanging out near street stalls blaring loud music.

When I asked them about a recent case of mass harassment in which women at a park were groped by a gang of boys, they told me the girls brought it on themselves.

"If the girls were dressed respectably, no-one would touch them," one of them said. "It's the way girls dress that makes guys come on to them. The girls came wanting it - even women in niqab."

One of his friends told me the boys were not to blame, and that there was a difference between women who wore loose niqabs and tight ones.

A woman who wore a tight niqab was up for it, he added.

But attitudes like these horrify many Egyptian men - like Hamdy, a human rights activist.

"I really feel very upset myself because I think about my family, my sisters and my mother," he said.

"Before Eid [the festival at the end of Ramadan], I was downtown and I had my sisters with me. It gets very crowded and I had my eyes everywhere, looking around and I shouted at a pedlar who got in their way. In our religion this is something that is not allowed."

The new government says it is taking the problem seriously - although many campaigners argue it is not a priority yet.

For women - like Nancy, who lives in central Cairo - it is a question of freedom.

"I want to walk safely and like a human being. Nobody should touch or harass me - that's it."