Iranian university bans on women causes consternation

- Published

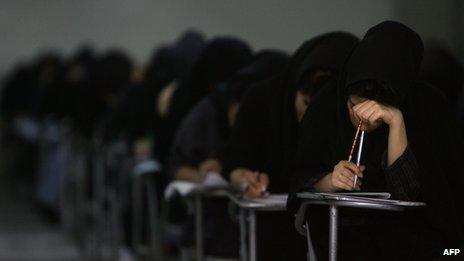

Female university students in Iran have outnumbered men for the past decade

With the start of the new Iranian academic year, a raft of restrictions on courses open to female students has been introduced, raising questions about the rights of women to education in Iran - and the long-term impact such exclusions might have.

More than 30 universities have introduced new rules banning female students from almost 80 different degree courses.

These include a bewildering variety of subjects from engineering, nuclear physics and computer science, to English literature, archaeology and business.

No official reason has been given for the move, but campaigners, including Nobel Prize winning lawyer Shirin Ebadi, allege it is part of a deliberate policy by the authorities to exclude women from education.

"The Iranian government is using various initiatives… to restrict women's access to education, to stop them being active in society, and to return them to the home," she told the BBC.

Higher Education Minister Kamran Daneshjoo has sought to play down the situation, stressing Iran's strong track record in getting young people into higher education and saying that despite the changes, 90% of university courses are still open to both men and women.

Men outnumbered

Iran was one of the first countries in the Middle East to allow women to study at university and since the Islamic Revolution in 1979 it has made big efforts to encourage more girls to enrol in higher education.

The gap between the numbers of male and female students has gradually narrowed. In 2001 women outnumbered men for the first time and they now make up more than 60% of the overall student body.

University entrance exams are highly competitive in Iran, with the number of female applicants increasing each year

Year-on-year more Iranian women than men are applying for university places, motivated some say by the chance to live a more independent life, to have a career and to escape the pressure from parents to stay at home and to get married.

Women are well-represented across a wide range of professions and there are many female engineers, scientists and doctors.

But many in Iran fear that the new restrictions could now undermine this achievement.

"I wanted to study architecture and civil engineering," says Leila, a young woman from the south of Iran. "But access for girls has been cut by fifty per cent, and there's a chance I won't get into university at all this year."

In the early days after the Islamic revolution, universities were one of the few places where young Iranian men and women could mix relatively freely.

Over the years this gradually changed, with universities introducing stricter measures like separate entrances, lecture halls and even canteens for men and women.

Since the unrest after the 2009 presidential election this process has accelerated as conservative politicians have tightened their grip on the country.

Women played a key role in those protests - from the traditionally veiled but surprisingly outspoken wives of the two main opposition candidates, to the glamorous green-scarved demonstrators out on the streets of Tehran and other cities.

Some say it was the prominient role of women in 2009's protests that has unnerved Iran's conservative leaders

Some Iranians say it was the sight of so many young Iranian women at the forefront of the protests in 2009 that unnerved the country's conservative leaders and prompted them into action.

"The women's movement has been challenging Iran's male-dominated establishment for several years," says Saeed Moidfar, a retired sociology professor from Tehran.

"Traditional politicians now see educated and powerful women as a threat."

'Islamisation'

In a speech after the 2009 protests, the country's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei called for the "Islamisation" of universities and criticised subjects like sociology, which he said were too western-influenced and had no place in the Iranian Islamic curriculum.

Since then, there have been many changes at universities, with courses cut and long-serving academic staff replaced with conservative loyalists.

Many see the new restrictions on female students as a continuation of this process.

In August 2012 Ayatollah Khamenei made another widely-discussed speech calling for Iranians to return to traditional values and to have more children.

It was an affront to many in a country which pioneered family planning and has won praise from around the world for its emphasis on the importance of providing families with access to contraception.

"People are more educated now and they are more concerned about the size of their families," says Saeed Moidfar. "I doubt that the government plans will change anything."

However, since the speech there have been reports of cutbacks in family planning programmes, and in sex education classes at universities.

It is not yet clear exactly how many women students have been affected by the new rules on university entrance. But as the new academic year begins, at least some have had to completely rethink their career plans.

"From the age of 16 I knew I wanted to be a mechanical engineer, and I really worked hard for it," says Noushin from Esfahan. "But although I got high marks in the National University entrance exam, I've ended up with a place to study art and design instead."

Over the coming months campaigners will be watching closely to track the effects of the policy and to try to gauge the longer-term implications.

- Published16 May 2012

- Published10 November 2010