Damascus suburb gripped by Syria's civil war

- Published

As the conflict in Syria continues, residents report savage fighting in areas which, up to now, have been relatively peaceful. Lyse Doucet, just back from Syria, says it is clear that more and more parts of the country are now being caught up in the rebellion.

On the wide canvas of a country at war, sometimes the smallest of places can tell the bigger story.

For me, that place is Barzeh.

You might struggle to find it on a map. But on my human map of Syria, this suburb of Damascus looms large.

I have gone to what seems like a very ordinary neighbourhood on all my recent visits. Each time it told an extraordinary story.

The people I met in Barzeh did not want to tell me their names. They did not want their identities known. But their acts of courage told me a lot about them, about Barzeh, about Syria.

My first visit there was about a year ago. Damascus then was described as a bubble - a city largely untouched by growing protests in other parts of Syria.

The capital, a stronghold of the regime, was heavily protected, policed by ubiquitous intelligence services. Any protest was forcibly suppressed.

In Barzeh, fear was palpable. As we stood outside the main mosque, the rare presence of foreign journalists drew a crowd. But they kept their distance from our microphones, gesturing with eyes or hands to tell us - they could not speak.

Most residents in Barzeh are too frightened of the army to speak to journalists or give their real names

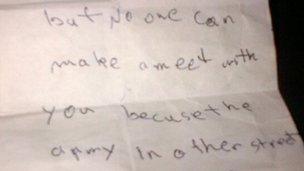

Then one man pressed a wad of crumpled paper into a colleague's hand. It read like this: "Thank you. But no one can meet with you because the army is in the street. All people are afraid."

Another man whispered as he brushed past me: "Look down that road." Syrian troops lay in wait.

Six months ago, I went back to Barzeh - to the mosque. An old man coming through the gate waved us on.

"Do not ask me what is happening. Go talk to the young people down the road." I looked down that road. Troops no longer circled the area. A few young men motioned to us.

Down that road, inside the neighbourhood, we found a place where fear was gone.

Men, women and children filled the narrow warren of of alleys, marching, shouting slogans against President Assad.

They urged us to keep following them, until we came to a house riddled with gaping holes, a house they said was used by the armed opposition, the Free Syrian Army, until the government attacked it. Syria's war had reached the suburbs.

And now, six months on, it has reached the very heart of Damascus.

On my latest visit, I found a different city.

Every day, plumes of black and white smoke billow across a bright Syrian sky. You can hear shelling night and day - explosions, sirens. Some neighbourhoods still retain their fabled charm - manicured parks where families picnic and young couples flirt, glittering shops of spices and sweets, cafes full of chatter.

But other neighbourhoods now lie in blackened ruin. The Damascus bubble is broken. Our repeated requests to the government to visit areas coming under bombardment were denied. "It is too dangerous," we were told. "Your protection is our priority."

Then one night I heard Barzeh was coming under attack. I insisted we should, at least, be allowed to go there.

So we went back to Barzeh, to the same mosque, the same road. This time a group of soldiers manned a checkpoint right in front of the mosque. They welcomed us, but told us we could go no further.

"The situation is fine," one man said. Another indicated, with a flip of his hand, that he was not so sure. They said we could talk to people close to the checkpoint, but they shadowed us, told a shopkeeper what to say.

Locals say a house riddled with bullet holes was used by the Free Syria Army until the government attacked it

But yet again, Barzeh still found a way to tell me its story.

First it was the mosque. The loud speaker rang out - announcing funerals. Two people, it said, had been killed in violence the day before.

And then I walked on my own down the largely empty road, as far as I could, without being called back by the troops.

A young woman and her son stood at the roadside.

How is everything? I asked the mother. Fine, she said. But then her young son boldly interrupted her.

"You should tell her," he insisted with an assertiveness that belied his years. "The helicopters attacked yesterday. We are staying in our houses because we are really scared. We are begging them to stop."

And yet, he said, there were still protests here.

Then, they had to go. And so did I, out of Barzeh, back into the heart of a city torn between those who still back the president, and fight for him, and those who do not, and fight against him.

That is Syria today. Everyone has a story. And it is a story of a war that gets worse. That is what Barzeh tells me.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 11:30 BST.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 11:00 BST (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.

'Message of peace'

'Message of peace'

Assad-supporting village

Assad-supporting village

Amid violent conflict

Amid violent conflict

Business as usual

Business as usual

Reporting from Syria

Reporting from Syria