The economics of Hajj: Money and pilgrimage

- Published

The Hajj pilgrimage netted Saudi Arabia an estimated $10bn in 2011

Millions of Muslims from all walks of life have converged on Saudi Arabia to perform the pilgrimage known as the Hajj.

The annual occasion has become a lucrative business in recent years, proving a great financial asset to the economy of the oil-rich kingdom.

Many pilgrims, however, struggle to reconcile their spiritual needs with their wallets.

Mohammed Zayan, a 53-year-old pilgrim from Tunisia, has waited a lifetime to perform the religious obligation, which does not come free.

"I spent up to $6,000 (£3,700) on my Hajj," says Mr Zayan, who wears the traditional white pilgrims' clothes.

"I thank God that he enabled me to save this amount of money but I'm sad I could not afford taking my wife and son with me."

The millions who come to Mecca every year bring billions of dollars to the Saudi economy.

Restaurants, travel agents, airlines and mobile phone companies all earn big bucks during the Hajj, and the government benefits in the form of taxes.

Last year, the 10-day event generated some $10bn (£6.2bn), according to the Chamber of Commerce in Mecca.

Worthwhile investment

The private sector also maximises its returns during Hajj, with investment in real estate an attractive proposition ahead of the pilgrimage.

The highest rents in Saudi Arabia are found in the holy city of Mecca, the birthplace of Islam.

Owners of hotels close to the main mosque ask for $700 a night, blaming the skyrocketing prices of land for the sharp rise in rates.

"I have been investing in this sector for 35 years. I remember when I first sold a metre of land in Mecca for just 15 rials ($3), now it has reached 80,000 rials ($22,000)," said Mohamed Saed al-Jahni, one of Mecca's real estate tycoons.

"The demand is higher than supply and that is why many buildings and hotels have been built in recent years to accommodate the increasing number of pilgrims".

Super-tall buildings are filling the Mecca skyline at an unstoppable pace.

The ancient city's centuries-old sites are giving way to glitzy luxury hotels, which are not affordable for many pilgrims.

The government says it is a necessary step, even if the construction comes at the expense of historical mountains dating back to the age of the Prophet of Islam Muhammad and his companions.

Spiritual relief

High-rise luxury hotels have sprung up all over Mecca

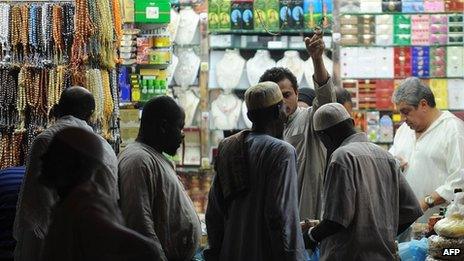

Selling Mecca souvenirs is another very lucrative business during the Hajj.

There are no official estimates for this profitable trade, but it is believed to bring hundreds of millions of dollars every year.

Ahmed Abdel Rahman, 43, will leave Mecca laden with presents and souvenirs for loved ones back in Mauritius.

"These are blessed souvenirs," he says, holding a bead he just bought at almost three times its original price outside the city.

The price of Mecca souvenirs is often eye-wateringly high and most of the products like prayer mats and beads are not made in the city, but rather in China.

But Mr Abdel Rahman says he feels a great spiritual relief when he spends his money in Mecca.

"I don't find shop owners opportunists but we help our brothers in Islam to make profit and make ends meet. This is a highly rewarded act."

Hajj is one of the five pillars of Islam and an obligation, provided a Muslim is financially and physically able.

The ritual, which demonstrates the unity of Muslims and their submission to Allah, has been carried out for nearly nearly 1,400 years.

However much it costs, Muslims will not stop coming to this spiritual and also commercial hub. They simply cannot do Hajj anywhere else.

- Published22 October 2012

- Published21 November 2011