Is Israel's missile defence a conflict game-changer?

- Published

(November 2012) The BBC's Ben Brown describes how Israel's Iron Dome works

For many Israelis, the recent fighting in Gaza provoked mixed feelings of both fear and a certain euphoria.

Fear because, for the first time, longer-range missiles from Hamas and other Palestinian groups reached the outskirts of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem; and euphoria because of the remarkable success of Israel's Iron Dome defensive system.

Experts claim that this had up to an 85% success rate in engaging missiles heading for populated areas. In the wake of the conflict, some Israeli experts claim that Iron Dome and other similar systems - that are either operational or in development - have changed the strategic rules of the game in the region.

As Israeli strategic analyst Ofer Shelah told me: "Since Syria's defeat in the air-battles during the Lebanon War in 1982, when some 82 Syrian aircraft were shot down for no Israeli losses and Syria's anti-aircraft defences were destroyed, Arab forces around Israel have sought to balance Israel's air superiority by amassing vast arsenals of rockets and missiles."

What was good for Syria was also good for its ally Hezbollah in Lebanon and for Hamas and other Palestinian groups in the Gaza Strip. They both saw rockets and missiles as a way of striking back at Israel despite its overwhelming military superiority.

Some estimates suggest that Israel faces some 60,000 rockets from Hezbollah alone and Hezbollah spokesmen have warned that rocket fire will rain down upon Israel's major cities in the event of any future confrontation.

Upper hand

Israel's military were for a long time sceptical about developing anti-missile defences which appeared to go against the traditional Israel Defense Forces' (IDF) doctrine that has always placed the emphasis upon offensive operations. It was only after the Second Lebanon War in 2006 that steps were taken to defend against short and medium-range rockets.

Ofer Shelah believes that the success of Iron Dome, "changes the equation drastically, back, in favour of the more technologically-superior nations".

"They can avoid a war of attrition against organisations or countries relying on missiles," he says, "and this creates a high degree of freedom for decision-makers."

Mr Shelah told me that, in this recent confrontation, Iron Dome had bought time for Israeli leaders. If it had not existed, he argues, then Israel might have felt compelled to make a decision on a ground operation much earlier.

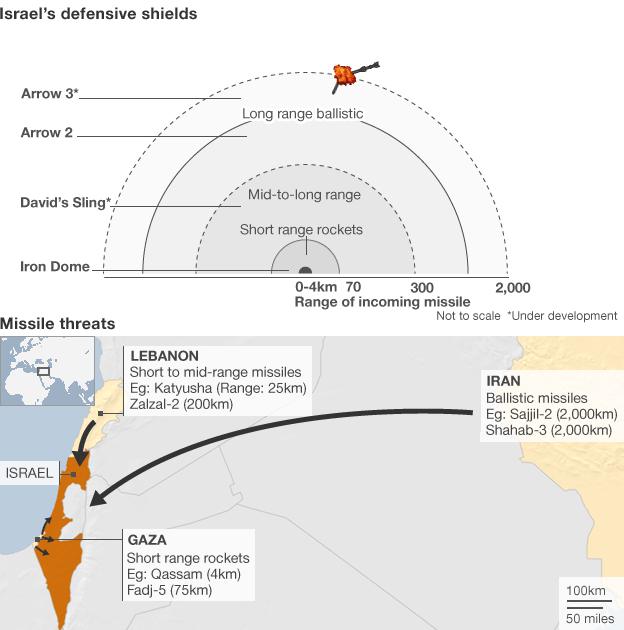

Israel already operates the Arrow 2 system intended to tackle long-range ballistic missiles, like the Iranian Shahab, that actually leave and re-enter the atmosphere. Its successor, the Arrow 3, which is already in development, expands the potential engagement envelope up to four times.

Advanced US-supplied Patriot surface-to-air missiles also have some capability against incoming ballistic missiles.

The Iron Dome has performed credibly during the recent Gaza operation, tackling rockets with ranges of between four and 70km. A new system, David's Sling, which was first tested this past weekend, will tackle missiles in the 70-250km range band.

"In a few years," says Mr Shelah, "Israel will have an active defence system which could neutralise the enemy's main threat."

Bombardment threat

Not everyone though is as convinced that Iron Dome has changed the military balance.

"Iron dome is not a strategic shift," said Jeffrey White, a defence expert at the US think tank, the Washington Institute for Near East Studies.

"It gives Israel some important advantages in responding to rocket fire, including reduction of casualties and damage; greater flexibility in responding to attacks; and some ability to frustrate the enemy's goals. But, it does not end the threat."

Indeed he argues that, for an attacker, a number of responses are possible.

On the one hand, an attacker could seek to saturate or overwhelm the defensive systems by firing large salvoes of rockets.

Israel faces the prospect of a barrage of missiles in future conflicts

He also notes that some of the missiles available to Hezbollah are more accurate, enabling them to mount precision attacks. Longer-range ballistic missiles, say from Iran, could one day also carry penetration aids to try to fool Israeli defences.

While it is US funding that has provided the bulk of the money for Israel's anti-missile defences, the fact remains that it is a hugely expensive business.

The interceptor missiles for Iron Dome, for example, are estimated to cost up to $50,000 dollars each. Hundreds could be used in a matter of days during a full-scale conflict.

Missile defence may not yet be a game-changer, but it must now be a growing consideration in the calculations of Israel's enemies.

The technological progress made is remarkable. Iron Dome's recent success will do no harm to its potential sales chances abroad, since more and more countries are becoming concerned about the missile threat.

But these defensive systems, however successful, do not offer some new cloak of immunity to civilian populations.

The whole panoply of civil defence, shelters and so on, will still be needed for those missiles that get through, and civilian life during any future conflict will continue to be disrupted.

These defensive systems fail to address the wider strategic picture in a more fundamental way too.

Reducing civilian casualties on the home front is clearly an understandable goal.

But, as a recent editorial in the liberal Israeli newspaper Haaretz, noted, "bragging over the performance of Iron Dome" is not a substitute for the policies that Israelis should be thinking about. "One cannot indulge in the delusion," it went on, "that a way has been found to maintain the diplomatic stalemate at a bearable price."