Bahrain tensions a trigger for Gulf turmoil

- Published

Protests continuing in Bahrain

The chant that has been part of the soundtrack of the uprisings in the Middle East since the beginning of 2011 is a rhythmic rendition of the words in Arabic that mean: "The people want the fall of the regime."

On a dark, drizzly night in Bahrain they echoed back off the scruffy, peeling walls of Muhazza, a village just outside the capital, Manama.

A few hundred Muhazza residents had gathered, defying the ban on public demonstrations that was imposed in October.

They waited for the police to arrive, alternating the chant about the fall of the regime with: "Down with Hamad" - in reference to Bahrain's King Hamad al-Khalifah.

The protesters were Shia Muslims, the majority sect in Bahrain. The Khalifahs, like most of Bahrain's establishment, are Sunni.

'Second-class citizens'

The trouble in Muhazza - and other Shia villages in Bahrain - is more than a little local difficulty.

Bahrain is caught up in the big forces that are reshaping the Middle East. They include the pressure for change and the desires and ambitions of major powers.

Bahrain is much poorer than its rich neighbours in the UAE and Qatar, and there are long-established economic grievances, particularly to do with unemployment and poor housing.

It is also the home port for the US Fifth Fleet, whose jobs include keeping the oil export routes open and reminding Iran of what the Americans could do to them if they so wished.

But the most significant single cause of unrest and outright violence in the new Middle East is religious sectarianism.

Bahrain lies between Sunni-ruled Saudi Arabia and the Shias of Iran, and has a long history of sectarian tension, between the Shia majority and the Sunni minority.

The Sunnis control most of the money and power. Some Shia families have done well out of the system, and have senior positions. But most have been treated like second-class citizens.

Shias and Sunnis are the equivalent of the Protestants and Catholics in the Christian world, often happy to intermarry and live peacefully alongside each other. But at times of tension, and sometimes because they have been inflamed by radical preachers, they can turn on each other.

Whiff of tear gas

It did not take long for the police to break up the demonstration in Muhazza.

The children seemed to sense them before they could see them, running for cover a few seconds before the police announced themselves with a stun grenade and a whiff of tear gas.

The adults scattered, running into shops and houses. The police made no attempt to pursue them, though locals said that in the previous few weeks there had been repeated violent raids in the early hours of the morning.

Ten minutes later, the police had moved on to another emergency call, and the street filled with defiant residents who began chanting again.

Women produced trays of food. The people of Muhazza started to enjoy themselves.

When protesters in Bahrain tried to emulate the revolution in Egypt by starting mass demonstrations in February 2011, the first slogans called for reform, not for the overthrow of the ruling family.

The security forces responded to what became an uprising with great brutality.

The first protesters also included a fair proportion of Sunnis, who were fed up with the way the country has been run.

But since the crackdown, the confrontation has increasingly been on sectarian lines.

In a moment of unusual openness for a Middle Eastern ruling family, the king commissioned and accepted the findings of an independent report into what happened, which confirmed that the security forces had killed and tortured protesters.

A year after the report, known as the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry, external (BICI), the ruling family is being accused of not doing enough to implement its findings, by its friends in the West as well as human rights groups and its critics inside Bahrain.

'Bringing unity back'

The US state department briefed journalists of its concern about the increasing violence in Bahrain, the limits put on rights of free expression and assembly, and the "excessive" use of force by the police and security services.

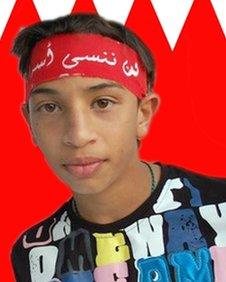

Ali al-Sheikh was killed by a tear gas canister fired by police at a protest

The Bahraini government denies the charges. It says it is working hard to implement the report, is determined to bring the different sections of society together and is making sure that the security forces follow a new code of conduct.

Justice Minister Khaled al-Khalifah dismissed accusations that the system still shields senior officers and officials who should be held accountable for the excesses committed under their command.

Lack of accountability is regarded as the biggest problem of all by Bahrain's allies. But the minister said Washington did not understand what was happening.

"If the government wanted to cover this they wouldn't have established BICI," he told the BBC.

"We are courageous enough and able to face this and deal with it. No-one will be able to hide under a cover of impunity.

"What we are trying to do is to establish a proper accountability for what happened in Bahrain… we want to bring back unity in a way that heals the earlier error."

'Marginalised' Shia

But in a sitting room that had been turned into a shrine to a dead boy, a grieving Shia mother had a very different view.

Mariam Abdullah sat surrounded by photographs of her 14-year-old son, Ali al-Sheikh, who was killed by a tear gas canister fired by the police during an anti-government demonstration in August last year.

A year after the report was published, none of its suggestions had been implemented, she said.

"I couldn't see any reforms," said Ms Abdullah. "We need equality between the two sects, especially in jobs, in the ministry of interior and the army, even in the ministry of justice.

"There's sectarianism in this country and the Shia sect, especially, is marginalised."

Like their Sunni brothers in Saudi Arabia, the Bahraini ruling family and its supporters believe that Iran is inciting the Shia protests in villages around Manama.

Mariam Abdullah said that suggestion was an insult.

Bahrain is a barometer for the Gulf. If the crisis here cannot be solved by the country's politicians, then Bahrain will export trouble to the region - sharpening Shia-Sunni sectarianism - and the dangerous competition between the Saudis and Iran.

The Americans fear that, without urgent political progress, the country will continue to fragment - and that, they say, will only benefit Iran.