Unusual jobs highlight restricted choices of Gaza youth

- Published

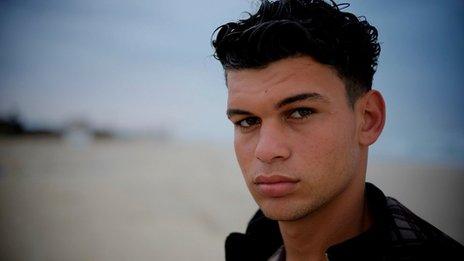

Eighteen-year-old Muhammad has been working in the tunnels for four years

Newsnight's Tim Whewell talks to two young people's whose jobs highlight the peculiarities of life in the Gaza Strip - Muhammad, who works in the smuggling tunnels into Egypt, and Madeline, who is the only woman in a fishing fleet restricted to trawling the waters inside the Israeli blockade.

It is not even dawn in Rafah, at the southern extremity of the Gaza Strip, when Busaina Ismail leans over her sleeping son Muhammad and tries, with difficulty, to rouse him.

It is a duty she says she dreads because she is sending him for another day's work in a place where many young men have been buried alive - the network of smuggling tunnels that run under the Gaza-Egypt border.

After two cigarettes and a glass of tea, he is just about wake. But not eager to go:

"This work," he says. "It's criminal. No-one should do it. Have you ever seen anyone dig their own grave? While you are digging, the tunnel might collapse. It could collapse any time and kill you."

Muhammad is just 18, but he has already been working full-time in the tunnels, digging and carrying heavy loads, for four years.

He hates the job, but he has little choice. His father suffers from a bad back, so Muhammad is the main breadwinner in the family of eight. And with unemployment in Gaza running at 28%, smuggling is one of the few occupations that provide a viable income.

Meanwhile, at the opposite end of the Gaza Strip, 22 miles (35km) away in the harbour of Gaza City, another 18-year-old is also setting off for a hard day trying to feed her family.

Madeline Kullab is Gaza's only fisherwoman. She too has an invalid father. She has been going out to sea almost every day since she was 14, despite attempts by Gaza's police force, run by the Islamist movement Hamas, which governs the Gaza Strip, to stop her working in an otherwise wholly-male industry.

Madeline, unlike Muhammad, loves her job. But both their stories show the hardships of growing up in a tiny overcrowded strip of land that has been blockaded by its neighbours Israel and Egypt for years, and was at war again with Israel only last month.

Madeline is the only woman working in Gaza's fishing fleet

The smuggling tunnels have flourished since Israel imposed its blockade, assisted by Egypt, in 2007, after Hamas came to power in Gaza.

Although travel restrictions for people crossing the Rafah border were eased in 2011, the shipment of goods from Egypt into Gaza remains blocked. Israel also restricts what building materials it allows into Gaza, fearing Hamas might use them for military means, although smuggling tunnels are used to get round the blockade.

Food and consumer goods have been allowed in legally from Israel for the past two years. But they are cheaper when brought underground from Egypt.

Muhammad's shifts last 12 hours, with only a half-hour break. The work is so exhausting that, like many other tunnel workers, he started taking the painkiller Tramadol. But he says he soon became addicted:

"I stopped eating, I stopped drinking anything," he says. "All I wanted to do was take Tramadol and work like a donkey. But it stopped working so well, so I increased the dose. Then one day I collapsed in the tunnel. I was carrying a big sack of flour. I started having a fit, I lost consciousness. That's when I decided to quit."

Muhammad says that for two months after that, he barely slept or spoke to anyone. He says he even tried to strangle himself. Now he is cured he says, but he would rather do almost any other job. He hopes the promise made in the ceasefire agreement that ended last month's conflict - to open crossings and ease freedom of movement - will be fulfilled.

That has not happened yet. But the ceasefire has already brought a small benefit to Madeline. Before, Israel - afraid of gun-running - only allowed Gaza's fishing boats to go up to three nautical miles offshore. Now, the limit has been extended to six miles.

Madeline Kullab: ""All I know is that we are born into war, we live in war, we'll die in war"

But Madeline's not impressed: "When they gave us another three miles, the catches got better. But in a week or two, the fish up to six miles will be used up too. Most fish are beyond even the new boundary."

In her family's breezeblock house in the Jabaliya refugee camp, she also has to worry about repairing the asbestos roof she says was damaged by the shock-waves from Israeli rocket attacks last month:

"We're very close to military targets, so there were a lot of attacks round here," she says.

Like Muhammad, she was born in 1994 - the year after the Oslo peace accords between Israel and the Palestinians.

But peace seems further away to her than it did to her father's generations. He remembers how, years ago, he worked alongside Israeli fishermen, sharing the same house. But Madeline - like Muhammad - has never even spoken to an Israeli.

"All I know is that we are born into war, we live in war, we'll die in war," she says.

Muhammad's not optimistic either. "I hope the tunnels will close," he says. "And there will be jobs, so we can leave this kind of work. But as you see, nothing has changed. We haven't won yet."

Correction 11 January 2013: This story has been amended to clarify that the shipment of goods into Gaza was blocked via Rafah, and restricted through crossings via Israel.