Profile: Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp

- Published

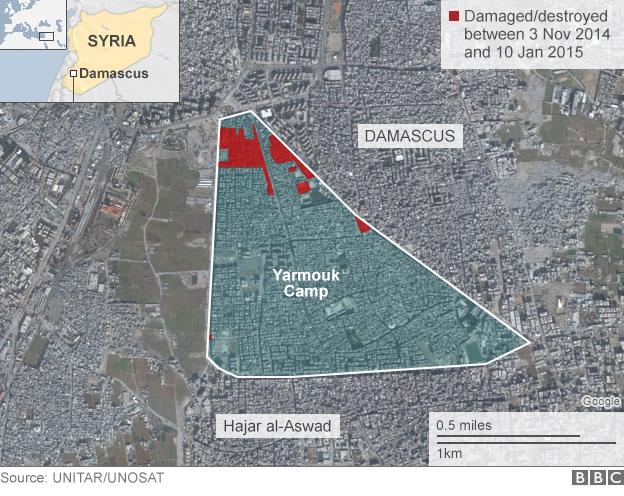

Yarmouk, once a home for 150,000 Palestinian refugees, has been devastated by Syria's war

Yarmouk was for years considered by many the de facto capital of the Palestinian refugee diaspora.

When the Syrian authorities set out in 1957 to build an unofficial camp for those who fled or were displaced from their homes during the Arab-Israeli war of 1948-49, they allocated land about 8km (5 miles) south of central Damascus.

Within a few years, the camp had become one of the biggest in the Middle East and one of the capital's most populous and important districts. It was home to more than 150,000 registered refugees.

But five years of attritional civil war in Syria devastated Yarmouk, taking a heavy toll on its Palestinian inhabitants. Rebel fighters seized parts of the camp and the regime of Bashar al-Assad besieged it for months. Rights groups said more than 100 people died of starvation.

Now fewer than 18,000 refugees remain, and they face increasingly desperate circumstances.

The jihadist group Islamic State (IS) launched an offensive against the camp in March and is thought to hold up to 90% of it. With shortages of food, water, medicines and electricity, one UN official described the situation for the civilians there as "beyond inhumane".

Thriving suburb

Before it was ravaged by war, Yarmouk had a well-established infrastructure.

It had its own mosques, schools and public buildings. Literacy and numeracy rates among Palestinians in the camp were among the highest not just in Syria, but across the Arab world.

Living conditions were far better than those in other Palestinian refugee camps in Syria.

The camp was officially run by the Syrian ministry of social affairs and labour and the UN Relief and Works Agency (Unrwa) provided health and education services. It became a thriving suburb of the capital.

Generations of Palestinians have lived in Syria, many of them at Yarmouk

Much of Yarmouk's success was owed to a law passed in 1956 that granted Palestinian refugees almost the same rights as Syrian nationals, particularly in the areas of employment, trade and military service. It also significantly increased their freedom of movement, something refugees resident in neighbouring countries did not enjoy.

And after the military coup of 1963 that propelled the Baath Party to power, Palestinians in Yarmouk launched organisations to "resist" the Israeli occupation of their homeland. Thousands of youths joined newly established groups like Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP).

Hundreds of these youths were subsequently killed in battles with Israeli forces, many during the invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

Palestinian fighters were able to reach the front line under the protection of the Syrian army, whose troops were deployed in Lebanon between 1976 and 2005.

In 1983, the residents of Yarmouk experienced difficulties when then-Syrian President Hafez al-Assad barred Yasser Arafat, the leader of Fatah and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO), from the country. The Syrian government came to see Yarmouk as an opposition stronghold.

Afterwards, residents began to concentrate on commercial, rather than political and military activities. Yarmouk became a centre of commerce in Damascus.

With the PLO's relations with the Syrian government strained, the Palestinian Islamist movements Hamas and Islamic Jihad sought to fill the political power vacuum in Yarmouk, recruiting scores of youths to their causes.

Hamas's political leader Khaled Meshaal lived in Yarmouk until he refused to endorse President Bashar al-Assad's handling of the uprising against his rule.

Once the Hamas Political Bureau had relocated to Egypt and Qatar in early 2012, they declared their wholehearted support of the Syrian opposition.

Drawn into conflict

The departure of Hamas left the residents of Yarmouk without any political representation or protection. An offshoot of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - the General Command (PFLP-GC), which supports President Assad - soon deployed fighters around the camp, saying they wanted to prevent infiltration by the rebel Free Syrian Army (FSA).

This did not, however, prevent Yarmouk from being drawn into the conflict. The FSA seized control of parts of the camp from the PFLP-GC and in December 2011 government warplanes bombed it for the first time.

The image that brought Yarmouk to the world's attention: thousands of refugees queue for food in February 2014

Since then, conditions for those left in the camp have deteriorated unrelentingly. The Islamic State militants who have overrun most of the camp are reportedly allied with another jihadist group in their push toward Damascus.

Yarmouk's remaining refugees are now caught in the crossfire between the jihadists, the rebels, and the regime and cut off from the food and supplies they desperately need.

A few hundred refugees reportedly escaped the camp in early April, but for the thousands still there life has barely been worse.