Qatar Direct: Old Doha

- Published

Qatar's capital city is experiencing rapid development and some of the sights of the old city are being swept aside

Doha, the capital of Qatar, is a city of contrasts. In a few decades it has been transformed from a crumbling pearling port to a gleaming metropolis. Today, its skyline is dominated by soaring skyscrapers but Old Doha - though fast disappearing - can still be found.

On the dusty, uneven pavements of Al Diwan Street, deep in the old quarter of Doha, Indian and Pakistani men sit cross-legged outside tea shops and restaurants.

It is a little after 7pm and despite the cool winds, dozens of men sit on chairs made of cardboard boxes. Others peer into the windows of empty second-hand electrical stores to watch television.

At one end of the road, men queue by the doorways of crowded supermarkets to buy essentials: boxes of teabags, milk, sugar, bread and soap.

The shops are dimly lit and poorly stocked - in sharp contrast to the modern, air-conditioned supermarkets on the other side of the city.

Nearby, large dining halls for labourers offer two courses of lamb curry and daal served with oven-baked rotis for 15 Qatari riyals, about $4. The equivalent meal, in a five-star hotel on the other side of town, would cost around 20 times that.

Old Doha lacks the glitz of the new developments but still attracts many to the area

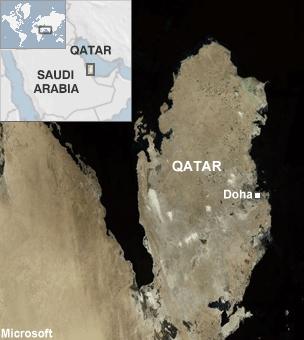

Qatar, the tiny Gulf nation that juts out into the Persian Gulf from the expanse of neighbouring Saudi Arabia, is a country of vast local and international aspirations.

At home, the emir, Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani has undertaken a far-reaching program to modernise this once sleepy pearl-diving community. Qatar now boasts several international universities, large-scale art initiatives and a diversified post-oil economy.

Abroad, Doha packs a powerful diplomatic punch. In recent years, it has made an effort to broker a peace deal in Afghanistan by hosting a foreign affairs office for the Taliban. The events of the Arab Spring have witnessed Qatar-sponsored political and military interventions in Syria and Libya.

Desert ice rink

In October, the emir visited the West Bank and pledged $400m for building projects in the Gaza Strip. While neighbouring states like Dubai and Abu Dhabi have enjoyed longer periods of transformation, only Qatar seems to understand that globalism is politics.

The ambition is driven by the country's immense reserves of fossil fuels. Qatar sits on the third largest known reserves of natural gas in the world, behind Russia and neighbouring Iran.

At home, it has played host to several international events. Qatar staged the pan-Arab Games in 2011. Last month, Doha was the site of Cop18 UN Climate Change Conference and in 2022, Qatar will host the World Cup.

This rapid growth has created a number of startling contrasts across the city.

Central Doha glimmers with skyscrapers, five-star hotels and luxury apartment buildings. The area looks like any other modern district, and is home to a large concentration of Western expats. In the evenings, pedestrians walk from their flats to local restaurants and shops.

International five-star hotel chains, such as the W and the Kempinski, stand next to incomplete residential buildings, slowly sprouting from the sand. City Centre, a busy shopping complex, features a food court, an ice-skating rink and a multi-screen cinema.

The cityscape Qatar presents to the outside world is defined by the forest of cranes and the soundtrack of construction machinery.

In Musherib, the old part of the city, however, time seems to stand still. The winding streets are often clogged with pedestrian traffic and taxis at weekends as labourers make their way to the shops on their day off.

Geographically, the distance from Musherib's cramped quarters to West Bay's bustling metropolis is only five miles. Aesthetically, they are worlds apart.

One informal survey in 2011 put the population of Musherib at 71% South Asian and overwhelmingly male.

The average monthly salary for labourers, drivers and cleaners is between 1,000 and 2,000 riyals - about $266 - $533, a fraction of the country's average monthly salary estimated by the International Labour Organisation at 7,401 riyals.

Mohammed Salim, 55, runs a "saloon" where he and his assistant cut hair. Salim, who has a jovial expression, was born in Peshawar, Pakistan.

When he arrived in Musherib 22 years ago, he says Doha was a quiet town with few modern amenities.

"I'd left Peshawar, a big city," he says. "Doha seemed very small. There were no big roads or malls."

Salim rents his premises from a Qatari sponsor. Like many immigrant workers, he pays a Qatari for his visa, which enables him to open a business. In return he shares any profits he makes.

Old Doha is a world away from the air conditioned shopping malls on the other side of town

Last year, he opened a second barber shop. He says his rent is cheap, but that he has noticed a drop in customers in recent years.

"With so many foreigners coming to Doha in recent years, the city has changed," he says. "People who would come here to have their hair trimmed now prefer to go to more upmarket hair salons in shopping malls."

Pointing to the street outside, he says: "This is the original Doha only there's a new Doha on the other side now".

Like the rest of Doha, Musherib is also facing the pull of modernity.

Affordable labour

The area is being slowly demolished to make way for mid- and upmarket housing. Shops are closing. Restaurants are disappearing. A refurbished souk featuring attractive boutique hotels and restaurants now sits on the site of former businesses.

In all, between 7,000 and 9,000 residents, a sizeable portion of the city's South Asian community, are expecting to be displaced. Equally affected are the thousands of labourers who visit the area at weekends.

Local rents will rise as the demolition exerts pressure on the retail sector.

For many of Doha's residents, Musherib's wealth is its abundance of affordable labour - drivers, gardeners, and repair men.

A few streets away, Ismail Said, 37, a native Pakistani, sells bootlegged DVDs for 35 riyals each. His shop interior boasts the suggestive posters usually associated with Hollywood and Punjabi cinema.

Migrant workers look through catalogues of photocopied DVD covers and point to their selection.

Sajid has prospered in Doha for over a decade, earning a wage he never would at home in Pakistan. However, he says he will return to Pakistan when the demolition of Musherib reaches his store.

Unlike his neighbours, he refuses to relocate to Barwa, a small satellite town for immigrant workers, nearly 10km (six miles) away.

"I like Musherib, I call this area my home," he says. "I won't be able to afford a business here once this area is gone. I will be sad, but I can't ignore that the city is changing."