Campaigns struggle to impress as Israeli elections loom

- Published

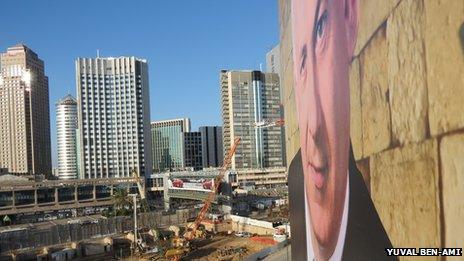

Netanyahu looks set to build on his record with a third term in office

With Israelis set to go to the polls next week, a gamut of parties is appealing to voters across a patchwork of communities, religions and cultures. Among the issues at stake, for the first time in years, economic and social matters are being seen by many as a priority in a land traditionally preoccupied with security.

Israeli journalist Yuval Ben-Ami has been travelling the country and finding an electorate more passionate about politics than about its politicians.

Going on a journey through pre-election Israel that began in mid-November, I was determined to encounter different groups within this overwhelmingly diverse society.

I expected to find a myriad of conflicting views, but conversations on the first two days as I travelled from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem all pointed in a single direction - Shas.

Initially, it seemed that everyone I met - Jewish, Muslim, religious or secular - intended to vote for this party, which traditionally represents Orthodox Mizrahi Jews - those hailing from across the Middle East and North Africa.

The first to declare his support though - a Hassidic man from Jerusalem's ultra-Orthodox Geula neighbourhood - confessed his decision was somewhat more random.

"Our rabbi said we should vote for any of the religious parties, in order to maintain an ultra-Orthodox presence in the Knesset [Israeli parliament]. I picked Shas," he explained.

It is not unusual for rabbis in some ultra-Orthodox communities, which account for about 10% of the population, to instruct their followers who to vote for, influencing blocs of thousands of votes at a time.

The following day it was a secular Jewish bus driver and an Israeli Arab shopkeeper who named Shas as their likely pick, though the shopkeeper doubted whether he would end up voting at all.

Both men came from the somewhat neglected blue-collar town of Ramle, and were attracted by Shas's socially minded values.

Recent polls predict Shas will win between eight and 12 seats in the 120-member Knesset - roughly the same as it has now. Despite holding relatively few seats, Shas has historically played a pivotal role in Israel's coalition governments.

The recurring reference to the party at my journey's start is largely coincidental, but relates to a phenomenon that is more meaningful.

Bennett factor

One thing common to the Hassid, the driver and the shopkeeper is that none of them cited ideological factors in explaining their preference for Shas.

For all three, it is by default. Ironically, at a time when Israel is shifting politically to the right, at a time of trial for its democracy, many Israelis are heading for the ballots unmotivated and cynical, if at all.

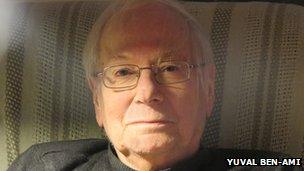

Kaniuk, like many on the left, fear the emergence of a more right-wing government

It is unlikely that these citizens misunderstand the importance of the upcoming election. Israelis think of politics incessantly and discuss it frequently.

The social justice movement of 2011 rekindled the public's interest in economic issues, and the recent Gaza offensive reinvigorated the constant debate about the peace process and national security. Israelis clearly care about politics. It's the parties many of them don't care for.

"What will follow these elections is this country's demise," predicted Yoram Kaniuk, a prominent, left-wing Israeli author and Tel Avivian.

Like many Israelis who identify with the left and centre, Mr Kaniuk is troubled not only by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's policies and right-wing coalition, but also by the rise of Naftali Bennett, who the polls predict will be the breakout surprise of this coming election.

Mr Bennett, head of the ultra-nationalist religious-Zionist Habayit Hayehudi (Jewish Home) party, represents a political approach more hawkish than Mr Netanyahu's, yet he radiates an all-Israeli quality that has appealed to even traditional centrist and moderate voters.

"Bennett reminds me of the European politics of bygone days," said Mr Kaniuk, alluding to the rise of the far-right led by demagogues in the 1920s and '30s.

"This is what my father escaped when he fled Europe."

Mr Bennett's growing number of supporters however see him as a plain-talking realist - a dichotomy which shows how far apart the left and right in Israel still are.

Disenchantment

With all his angst as to the country's future, Mr Kaniuk is hard-pressed to identify a party he can eagerly support.

Over the past few months, he has oscillated between the Labour Party, led by Shelly Yachimovich, and the new Hatnua (The Movement) party, founded by former Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni.

These two parties, together with former newsreader Yair Lapid's new Yesh Atid (There is a Future) party, represent a surplus of centrist groups with limited ideological differences among them.

The elections have not managed to generate much excitement among voters

The parties' leaders have thus far refused to join forces to form an anti-Netanyahu, anti-Bennett cluster, leaving centrist and leftist voters further disillusioned. The danger the voters see before them is near and clear, yet the politicians fail to impress.

It was a sentiment which recurred again and again as I journeyed on to the far north and south.

I met with the mayor of a West Bank settlement, an elderly kibbutznik, soldiers, and representatives of the Bedouin and Druze communities. The prevailing feeling was not one of indifference, but of general disenchantment.

Over time, Naftali Bennett's presence felt more and more pronounced, assuring the right and troubling the left, yet on neither edge of the spectrum did the sense of urgency seem to win over the scepticism.

In the city of Modiin, a bastion of Israel's beleaguered middle class, sandwiched between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, I spoke to satirical cartoonist Amir Schiby.

Like others on both the left and right, Mr Schiby believes that Israeli scepticism serves to strengthen the current government and its policies.

He summed up his take on the election with the following axiom: "When a leftist feels despair, he doesn't bother to get out and vote. When a rightist feels despair, he gets out and votes for Netanyahu."

The polls seem to agree, predicting around 34 Knesset seats for Mr Netanyahu's Likud, but saying nothing of whether people are actually impressed with it.