The complicated legacy of Egypt's Hosni Mubarak

- Published

Mubarak, Egypt's military and the Muslim Brotherhood: Two out of three remain powers in the land

Two years ago the uprising that overthrew Egypt's autocratic President Hosni Mubarak began. He ruled for 30 years and his political legacy continues to shape what Egypt is currently going through.

Hosni Mubarak's focus on security enabled him to crush an Islamist insurgency and sustain official support for the 1979 peace treaty with Israel, making him a staunch ally of the West. However it also produced political stagnation.

At the same time the Muslim Brotherhood, an Islamist political group founded in Egypt in 1928, became stronger during the Mubarak era, even though it remained an illegal organisation.

The government attempted to contain Islamists by co-opting their agenda. It was an approach that also stoked sectarian division.

In the later years of his presidency, Mubarak was given credit for economic reforms that successfully raised overall growth and investment. However they failed to alleviate poverty; some 40% of the Egyptian population continued to live on $2 a day or less.

Ultimately, a sense of economic injustice helped create the conditions for the 18-day uprising that unseated Mubarak.

There was also anger over the brutality of security services and at undemocratic practices including the president's assumed plan to hand power to his son.

Early hopes

There had been very different hopes for Mubarak when he became president in 1981 after Islamist gunmen assassinated his predecessor, Anwar al-Sadat.

After taking over from Sadat, Mubarak carried out limited reforms

According to historian Afaf Lutfi al-Sayyid Marsot, the former air force commander and vice-president was known for "efficiency and his no-nonsense approach to work".

His government fixed infrastructure and provided new roads, sewage facilities and telephone circuits. It solved the problem of bread subsidies, which had previously caused riots, with a reduction in the size of loaves.

For a while, Mubarak even looked like a reformist.

Although he kept emergency laws, more than 1,500 political prisoners from all factions, jailed under Sadat, were freed. Many restrictions on freedom of speech were lifted.

General elections saw greater openness. More political parties formed and the Muslim Brotherhood was able to contest elections in 1984 and 1987 with its members running as independents.

However the president still chose the prime minister and the entire cabinet was answerable to him.

Islamist violence

While Mubarak tried to reverse the tide of Islamic extremism, under his rule the problem continued to grow.

Militant groups such as al-Jihad and Gamaat al-Islamiyah (Islamic Group), which co-ordinated Sadat's assassination, were targeted in a clampdown.

Many thousands of Egyptians were arrested during waves of violence in the 1980s.

At the same time the government tried to divide the Islamic mainstream from the extremists. Moderate preachers were given prime-time TV slots, the authorities extended their control of mosques and there was broad censorship in the name of Islam.

Islam regained its central role in identity in Egypt during Mubarak's rule

It was not until the 1990s, after dozens of Western tourists were killed at a temple in Luxor, that militancy in Egypt receded.

But it left a different society. In his book on Cairo, the journalist Max Rodenbeck states: "Religion had reclaimed the absolute centrality to Egyptian identity that had been challenged for a hundred years."

The Coptic Christian community, which accounts for some 10% of Egypt's population, complained of wider discrimination.

"Our school curriculum is infiltrated by Islamisation and our children are taught that Islam is the one and only religion and the only route to anything good and pious in life," says editor of the Coptic newspaper, Youssef Sidhoum.

Western support

Under Mubarak, foreign aid flowed into Egypt. To the West he remained a strong, reliable leader in a tumultuous region.

By 2011, Washington was sending an annual aid package of $1.3bn mostly in the form of military assistance.

"Hosni Mubarak was an ideal partner for the United States, as long as Washington focused on stability in the present without much thought about long-term implications," says Middle East analyst, Marina Ottaway.

"Relations with Israel were cold, but there was no danger of his reneging on the peace treaty."

Mubarak was looked to as a guarantor of stability in the Middle East

Tensions did come to the fore in 2005 when President Bush was pressing his Freedom Agenda. This coincided with large demonstrations calling for political reform in Egypt.

Mubarak was persuaded to allow a contested presidential election for the first time but the vote was subject to fraud and rigging. A popular politician, Ayman Nur, who finished a distant second to the incumbent, was imprisoned on trumped-up forgery charges. While behind bars, his party was split by infighting and its headquarters in central Cairo were set on fire.

All opposition forces were systematically spied on and squeezed under Mubarak.

His security apparatus regularly rounded up dissidents. To monitor groups the Interior Ministry had its General Directorate for State Security Investigations while the tough methods of the Central Security Forces could be relied on to stifle demonstrations.

When criticised by his Western allies, Mubarak would play up the threat posed by Islamists.

"I'm sorry to say that he fooled the Europeans as well as the United States. He played on historical fears and ideas of a so-called confrontation between Islam and the West," says Abdul Mawgud Dardiri, a former MP for the Muslim Brotherhood's political wing.

Islamist successor

Ultimately however it was Mubarak's presidency that created the conditions whereby a former Muslim Brotherhood leader, Mohammed Morsi, was elected to succeed him.

Mubarak's years of mollifying the Islamists, combined with his government's failure to address high poverty rates and dire social services, boosted the popularity of the well-established Muslim Brotherhood.

The Muslim Brotherhood has a wide network of grassroots supporters

The Brotherhood had a vast grassroots network and provided hospitals and handouts.

In comparison to liberal and leftist groups, it had strong internal structures. Analysts say it adapted to its peculiar status whereby it was banned but largely tolerated.

"Unwittingly Mubarak helped the Muslim Brotherhood when he restricted the activities of legally organised parties," says Mustafa Kamal al-Sayyid, a politics professor at Cairo University.

"It had a free hand working among the public, through charitable organisations, mosques, some newspapers and professional organisations."

Economic failure

The corruption of the Egyptian government added to the appeal of the Brothers - who had a relatively clean image.

In the last decade of Mubarak's rule, his younger son, Gamal, a former investment banker had filled the cabinet with his inner circle of businessmen friends. He headed the powerful NDP policy committee.

Neo-liberal economic policies helped increase GDP to $145bn but only widened the gap between rich and poor. Egypt suffered from a huge bureaucracy and public sector.

While the government failed to meet the challenge of reforming education and health services it continued to press ahead with selling off state-owned assets - from factories to land for development. Mubarak's cronies were seen to be the beneficiaries.

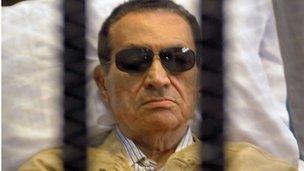

Mubarak is now behind bars awaiting a retrial

Such developments may have angered the general population, but it was steps like a series of constitutional amendments, apparently designed to ensure the transition of power to Gamal, which lost him the support of the military - a crucial pillar of his government.

"The wish of his wife to have her son succeed Mubarak is what really led to his downfall," argues Mustafa Kamal al-Sayyid.

The armed forces, which had overthrown a monarchical system in 1952, clearly objected to an inheritance of power and the idea of a non-military man as their commander-in-chief.

Its leaders eventually made the calculated decision to back the protesters during the revolution rather than Mubarak hoping to protect their own wealth and privileges.

They went on to take the reins of power through a rocky 18-month period of democratic transition and then had to be forced to hand them over.

Egypt's longest-serving president is now in prison awaiting his retrial on charges of corruption and ordering the killing of protesters during the revolt that unseated him.