Yemen: A rare 'success' 'at risk

- Published

Yemen's army has been celebrating recent successes tackling al-Qaeda in the country's southern province

As turmoil seeped across Arab borders in 2011, the UN Security Council threw its weight behind a political transition plan for a nation roiled by protests and violence, stopping the drift towards civil war and leading to the resignation of the authoritarian leader.

No, this is not a fantasy about what might have been for Syria. It is the reality of what happened in Yemen.

And it is the reason council members see Yemen as a rare success story in their track record on the Arab uprisings, last week making it the destination of their first visit to the Middle East in five years.

But it is a fragile success that risks unravelling in the coming months and may prompt the Security Council to impose sanctions on "spoilers" who are blocking progress.

There are many reasons why council members, who are deeply divided on Syria, were able to agree on Yemen.

None had invested the kind of strategic ties in the Yemeni ruling family that, for example, Russia had in the government of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad.

And all were alarmed that al-Qaeda had taken advantage of the chaos to establish a fiefdom close to key shipping lanes.

Willing to negotiate

The dynamics inside the country were also different from Syria, not least the fact that the President Ali Abdullah Saleh never used the full weight of the army against civilians. That is one of the reasons the opposition, which was relatively united, was ultimately willing to negotiate.

"The regime had been counting on a divided Security Council," says the UN's Yemen envoy Jamal Benomar, explaining the impact of the UN resolution backing the transition plan put forward by Yemen's neighbours, the Gulf Co-operation Council.

"It did not expect a resolution - let alone a unanimous one - and feared further measures.

"So that's how it started: a united Security Council, a resolution that created momentum, and the parties agreeing to meet face-to-face. Both sides asked me to facilitate and after a week, we had a deal."

The GCC deal called for Mr Saleh to step down in exchange for immunity and delegate powers to his Vice-President Abdo Robo Mansour Hadi.

Feuding politicians then formed a national unity government to oversee a two-year transition period meant to lead to parliamentary elections in 2014.

Key to the transition is a National Dialogue Conference (NDC) tasked with revising the constitution before the elections.

It is supposed to draw in constituencies who were either previously ignored or who rejected the agreement: the youth who led the protests, Huthi Shia insurgents in the north, and southern secessionists known as the Hiraak.

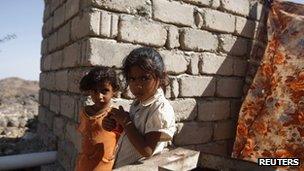

Yemen is suffering multiple crises such as food and water shortages and many have been displaced by violence

Preparations for such a body in this fragmented country have involved torturous negotiations.

Already halfway through the transition period, details were not finalised in time for a launch ceremony with the Security Council in the capital city Sanaa, which went ahead anyway.

In the meantime, former President Saleh continues to exercise influence through his political party and his relatives, chief among them his son who holds a senior position in the military.

National dialogue

Mr Saleh is accused by various parties of blocking or even sabotaging progress.

This, says Britain's UN Ambassador Sir Mark Lyall Grant, is the biggest weakness of the transition agreement.

"In taking forward the national dialogue… the biggest threat to that is the continued presence of ex-President Saleh in the country and his attempts to derail that process," he said.

Sir Mark, who led the trip to Yemen, says the Council will be considering whether to impose sanctions on Mr Saleh and others who are undermining the process, when it meets this week.

In fact, the agreement is vulnerable to spoilers from all sides, since it was struck between Yemen's two main power blocks, both of which could see an advantage in wrecking it if their interests are not protected.

These include the Saleh family on the one hand and, on the other, the powerful al-Ahmar family which backs General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, who defected during the uprising and mounted a military challenge to Mr Saleh.

Both command troops loyal to them, both retain control over much of the country's resources and both are regarded by independent activists as part of the traditional elite responsible for the country's dysfunctions.

Bold security reforms decreed by President Hadi would diminish their power, but these have not yet been acted upon.

It is important for the UN to maintain an impartial approach on the question of spoilers, says April Longley Alley, the senior Yemen analyst for the International Crisis Group think-tank.

"Sanctions have to be based on specific actions and a clear connection between actions and undermining the agreement," she says, "and not necessarily because of the rhetoric from one side or the other."

And the power struggle in Sanaa is not even the most difficult problem the National Dialogue Conference will face, adds Ms Alley.

"There are substantive issues to deal with - whether or not Ali Abdullah Saleh or General Mohsen remain - that will require compromise on the structure of the state, on resource sharing, and so on," she says, primary amongst them the issue of Southerners who feel they got a raw deal from the unification of the country in 1990.

So far none of the key players amongst the Hiraak have bought into the National Dialogue process, although some have indicated openness to the possibility of a federal state.

In theory, the NDC can provide the forum to transform an agreement between elites that stopped a slide to civil war, into a new national pact.

"It's the first time that politics is being made by the people and not just from backroom deals between political elites," says Mr Benomar, "but if there's no agreement in this national dialogue we could be back to square one.

"On this model of a peaceful negotiated transition, the jury is still out: it's moving forward, but it could still collapse."

To talk about Yemen as a success, then, is premature. The best one can say at this point is that, unlike Syria, it is not a failure.