Neighbours at war in Lebanon's divided city of Tripoli

- Published

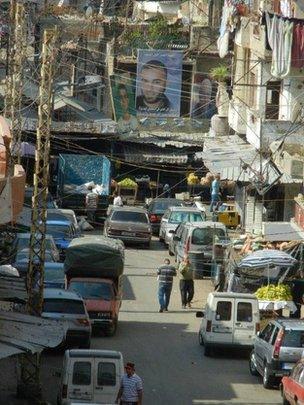

Fighting takes place from balcony to balcony in Jabal Muhsin

Abu Rami's eyes look like ball bearings - cold killer's eyes. And he is, without doubt, a killer. But today, he says, he is ready to die.

Thirty-five years a militia leader, a gunman since his teens, Abu Rami fought in most of Lebanon's many vicious little wars. Who knows how many were killed on his command or perished at his hand? As he puts it, his life has been "a bit brutal".

Abu Rami has been shot more than 30 times, and was once disembowelled by an explosion from a Palestinian mortar shell. But the will to live was strong in this furious little man - he held his own guts into his abdomen and staggered off to a field hospital. His stomach is a still gruesome mass of ageing scar tissue.

In the northern city of Tripoli they call him "Jabbar", which means "mighty". Or he is known as "the living martyr of Jabal Muhsin".

Hard man's tears

Men like this rarely talk to journalists. They do not open their mouths, let alone their hearts.

A sniper took a shot at Abu Rami's daughter Maya, but narrowly missed

But now Abu Rami has been finished off - by love. He seemed about to cry as we interviewed him on camera.

"I had three sons, but they were born in wartime," he explains in his low tone. "But my daughter Maya... was different.

"Maya made me feel the taste of fatherhood for the first time. Maybe if I cry, I can't let my kids know about it. I have this feeling that I'm responsible for our area. So I can't show emotions.

"But Maya has a very special place. The only girl I have. I don't want her to be affected by this environment."

It has taken 50-odd years for Abu Rami to grow himself a heart.

Because of a smiling, pink-obsessed 12-year-old girl, he is learning how to love and he thinks it has weakened him.

His eyes gleamed through the darkness, welling up with a hard man's tears. But, God knows, there is enough to cry about here on Jabal Muhsin.

Always a next time

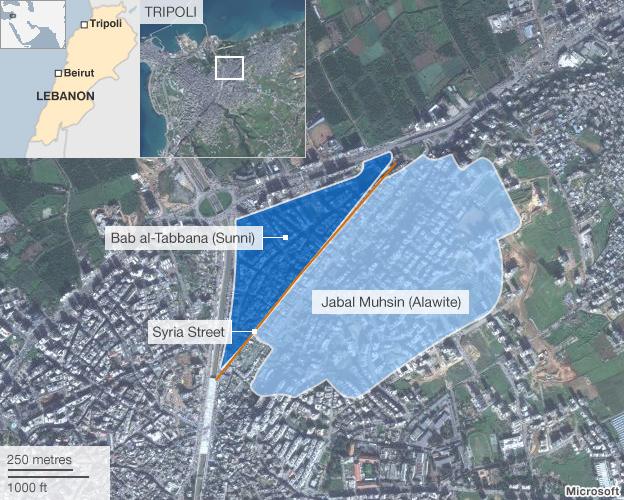

Two slum communities - one Sunni Muslim, the other Alawite - have been slugging it out since the 1970s. Like a couple locked in an abusive marriage, neither partner has the energy or will to escape the futile, bloody conflict that has come to define these two communities.

The Alawites once ruled the roost here, back in the 1980s, when Lebanon was occupied by Syrian forces, whose then President, Hafez al-Assad, was a member of the heterodox Shia sect.

But now their 50,000-strong population is crammed onto a hilltop called Jabal Muhsin. Surrounded by hostile Sunni areas, it is effectively under siege.

The majority of Tripoli's inhabitants are Sunnis who support the uprising in Syria

Every few weeks, armed clashes erupt and the neighbours go at each other with sniper rifles, machine-guns, rocket launchers and mortars. People die, homes burn, livelihoods are destroyed.

Then after several days of collective madness, the Lebanese army sends in its "peacekeepers". The guns fall silent, and the two communities bury their dead and prepare for the next time. In Tripoli there is always a next time.

The civil war in nearby Syria has also given fresh impetus to this feud, with the different Tripoli neighbourhoods backing opposite sides in that conflict.

Posters of Bashar al-Assad, who succeeded his father Hafez in 2000, are everywhere on Jabal Muhsin, while rebel Free Syrian Army flags outnumber Lebanese ones in the Sunni areas nearby. It is no small irony that the thoroughfare which forms one of the major frontlines here is itself called Syria Street.

But what does sectarian warfare look like when it becomes entrenched as a way of life?

On the one hand it looks like Abu Rami: exhausted, remorseful and paranoid after a lifetime in gun battles and chaos.

And now everything he had achieved as a fighter and leader is rendered meaningless by the terrifying realisation that his beloved young daughter might herself grow up surrounded by violence or die in it.

Abu Rami has set up CCTV cameras all around his block of flats. It is not burglars that concern him, but car bombs.

'Non-believers'

Entrenched sectarian conflict, on the other hand, also looks like Sheikh Bilal al-Masri.

He is a Salafist street preacher in his 30s who owns a small mobile phone shop in Bab al-Tabbana. The predominantly Sunni district lies below, in the shadows - and the gunsights - of Jabal Muhsin.

Charismatic and politically ambitious, Sheikh Bilal's every waking hour seems dominated by his hatred of the Syrian regime in Damascus - and its Alawite allies up on the hill. With long hair and wild eyes, he reminds me of a young Rasputin.

Sheikh Bilal is today where Abu Rami was 30 years ago: young, trigger-happy and eager for the fight.

When he is not preaching jihad or selling phones, he leads a small militia of local toughs. And when the clashes break out, he is a dab-hand with a sniper rifle, shunning modern assault weapons for his beloved bolt-action Lee Enfield.

Sheikh Bilal is also a killer. But unlike the war-weary Abu Rami, his tail is up.

He thinks that the slaughter in neighbouring Syria will lead to the overthrow of the Assad regime that back in the 1980s murdered his father, his friends and so many of his neighbours.

How fatherhood is changing ingrained views of the conflict in Tripoli

When that day comes, he is sure that the Sunnis of Bab al-Tabbana can rid Tripoli of the "non-believers", as he calls his Alawite enemies.

"Throughout my life, I've never seen anything good coming from the Syrian regime, or the non-believer sect. I've only witnessed death and killings, jail, torture, displacement, rape, looting."

Potentially a very dangerous man, he is also charming and gregarious. When we film him at home and he is playing with his four-year-old son, Muawiya, he seems like any indulgent father anywhere. But once the TV news moves onto the war in Syria, he starts coaching the lad.

"What does Bashar al-Assad do?" Sheikh Bilal asks.

"He kills people!" his son replies.

"And what does he do with kids?"

"He slaughters them, dad."

"Who? Bashar the criminal?"

"Uh-huh."

Muawiya is barely out of nappies and he would probably rather watch cartoons than Free Syrian Army propaganda. But his head is being filled daily with sectarian chauvinism and thoughts of war.

As we interview his father, Muawiya starts firing an imaginary rifle made from a stick. He is very specific in his actions - it is an imaginary bolt-action sniper rifle.

"The sound of bullets and rockets scares him and he cries," Sheikh Bilal tells us. "This will definitely affect him. When he grows up, it will affect him, the same as it happened to us. So I don't want this to continue."

Paying the price

But it may already be too late. Out on the streets of Bab al-Tabbana we film other young boys playing war games. They take aim and shoot their toy rifles uphill towards Jabal Muhsin.

Up on the Jabal, it is a mirror image. The kids point their plastic Kalashnikovs down the slope, as their fathers do in real life.

There are fears that the sectarian clashes in Tripoli could spread throughout Lebanon

And yet nobody really wants this war - or so they say.

The young men who make up the militia on both sides look identical in their skinny jeans, knock-off Adidas weightlifter vests, baseball caps and Maori-style tattoos.

They want jobs and investment in their slums. They want politicians who pay attention to their troubles after election time is over. They want to get married and raise families in normal conditions.

Up on Jabal Muhsin, a mournful Abu Rami, who has contributed more than his fair share to this mess, watches terrified as the grasping fingers of war threaten to reach out and snatch his beloved daughter Maya.

"I wish I could open my arms and bare my chest to them," he says.

"Let them kill me, I'm ready... But I don't want my kids and their kids to pay the price. I'm ready to pay the price. And if this would make them happy, so be it."

If only things were that simple.

Two weeks after we finished filming, Maya was out on the balcony collecting the washing when a sniper took a shot at her. The bullet missed her head by five centimetres.

This time she was lucky. But this is Tripoli, and in the war of neighbours and enemies, there will always be a next time.

My Neighbour, My Enemy was first broadcast on BBC Arabic TV.

- Published10 December 2012

- Published24 October 2012

- Published29 June 2012