Syria crisis: Are the two sides ready to talk?

- Published

- comments

The UK and US have been sending medicines, generators and other equipment to help Syrian refugees

At this week's upcoming international conference in Rome, the US and UK will try to reassure the main Syrian opposition umbrella group, the Syrian National Coalition (SNC), that further aid is on its way and insist the West has not abandoned the anti-Assad cause.

The Rome meeting, which the SNC had threatened to boycott, comes at a moment of real uncertainty for the opposition.

Diplomacy and exhaustion seem to have brought the warring parties to a point where they are nearly ready to sit down together - something both sides have baulked at doing so far.

A meeting, slated for Moscow next week, involves the Assad regime setting aside its refusal to talk to the armed opposition, and the SNC close to abandoning its insistence that the president step down as a precondition for negotiations.

I say "close" because there is some uncertainty about whether the SNC leader, Moaz al-Khatib, has the backing of his wider movement on this.

Frustratingly for those who have favoured intervention in support of the uprising, such as US Senator John McCain, or former UK prime minister Tony Blair - the change in mood is a direct result of recent reverses for the opposition on the battlefield and of the disparity of weapons employed by the two sides.

Former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair says Britain should be taking a far stronger line on Syria.

A senior diplomat says there was recently, "an interruption of lethal supplies from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Turkey", while the Assad forces have benefitted from the arrival of several large shipments of Russian weapons.

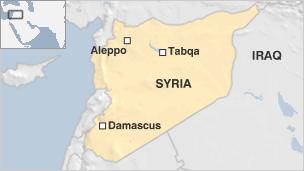

As a result, rebel claims late last year that they were about to take Damascus have been confounded, government forces have reportedly won back some small areas, for example in Homs, and up to four Scud missiles per day have been pounding anti-Assad neighbourhoods in the northern city of Aleppo.

The question of how or why weapons supplies to the SNC and more militant groups were interrupted is a mystery, but it appears to have happened at the end of last year and early 2013.

Normal service has apparently been resumed now, with the querulous Saudis and Qataris agreeing to focus on the southern (via Jordan and Lebanon) and northern (via Turkey) supply routes respectively.

Rivalry between these two external actors is intense, as is that between the Syrian groups vying to receive the arms, and the temporary halt may have been necessary to prevent internecine conflict breaking out between these armed factions.

Where does this leave the West? If the notion that both sides have now come close to negotiating because of setbacks on the battlefield is right, would not arming the rebels now simply re-ignite the fight and torpedo talks?

The White House, it is clear, does not wish to send weapons, let alone bomb President Bashar al-Assad's forces.

Sen McCain's questioning in recent hearings has exposed that President Barack Obama feels so strongly on this issue that he overruled advice from his defence secretary, Leon Panetta, and the former director of CIA, David Petraeus, who favoured sending arms.

As for the British, they have long-standing legal objections to arming insurgent groups, something that manifested itself from Bosnia in the 1990s to Libya more recently.

They, and the US have already been sending medicines, generators, and other equipment to help refugees, so what more can they do?

The current debate, I have learned, surrounds sending armoured cars, and equipment such as heavy diggers and lorries to help deal with the consequences of Scud strikes in northern Syria, some of which have buried dozens of people. There has also been a discussion about sending night vision equipment.

The US and UK are thus tip-toeing very close to the line of arming their chosen allies in the SNC.

Armoured land rovers sent for use as ambulances or to ferry around the leaders of the opposition might soon be photographed with a machine gun bolted on top or simply used as troop transporters. Diggers and other construction equipment might also be set to work building new routes around government strongholds, easing opposition operations.

Where would all this leave putative Russian-mediated talks between the SNC leader and Syria's foreign minister, Walid al-Muallem? Most seem to think the two sides may be sufficiently exhausted from a struggle that has cost more than 70,000 lives, to think seriously about talking to one another. Whether they are ready to do a deal, is quite another matter.

But the current moves to step-up supplies to the anti-Assad groups may also be intended to empower them in forthcoming talks.

- Published26 February 2013

- Published9 February 2013