Bahrain sickle cell death rise causes concern

- Published

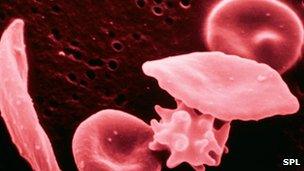

Red blood cell abnormalities caused by sickle cell disease

A large rise in the number of sickle cell disease deaths in Bahrain has prompted concern.

The Gulf island kingdom has a high incidence of the genetic red blood cell disease, but in 2012 the number of people in Bahrain who died from sickle cell disease (SCD) rose from 32 the previous year to 50.

Two experts contacted by the BBC have said that the rise may be linked to the heavy use of teargas by security forces policing unrest in the kingdom.

SCD causes red blood cells to lose their shape and become sickle-shaped (like a crescent moon). Sufferers have persistent anaemia coupled with episodes of extreme pain. The disease, which is incurable, attacks organs such as the lungs and the spleen.

Painful episodes can be triggered by a variety of causes, including stress and a shortage of oxygen. Tear gas inhalation restricts the flow of oxygen and causes acute, temporary physical stress.

Over the past two years the authorities in Bahrain have used what Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) has called unprecedented levels of CS gas in an attempt to bring ongoing unrest under control.

In a report released in August 2012, external, PHR stated: "The extensive and persistent use of this so-called non-lethal chemical agent now in Bahrain is unprecedented in the 100-year history of tear gas use against civilians throughout the world."

There is as yet no proven link between sudden sickle cell deaths and the heavy use of teargas in Bahrain. But could the teargas be associated with the jump in deaths?

Different views

The deaths prompted the head of the Bahrain Sickle Cell Society to speak of a "crisis" in November 2012.

"Last year we had an average of about 2.5 deaths per month but this year the number has almost doubled. We are almost on the verge of a crisis in Bahrain," Zakryia al-Kadem was quoted as saying in the local press.

However Dr Shaikya al-Arrayed, head of the genetics department at the country's main public hospital Salmaniya Medical Complex, denied there was a crisis.

Violent standoffs between police and protesters have become a daily occurrence

"That is not true, as we have reduced the incidence by 75% among newborns (and) we are taking more care and improving the management (of SCD) and updating treatment," she said in a written reply to questions from the BBC.

Dr Arrayed said there was "no spike of deaths", adding "these are usual figures, in the scientific term it is called natural SCD deaths".

She also cited statistics that show the incidence of SCD among newborns has been reduced by 75%, the result of screening programmes started more than two decades ago.

Other experts contacted by the BBC have taken a different view. Dr David Rees is a consultant and senior lecturer in paediatric haematology at King's College Hospital (KCL), London. He is an expert in sickle cell disease, and other inherited red cell abnormalities.

He told the BBC the jump in deaths should "set alarm bells ringing".

Pointing to figures that show the death rate rising from 23 in 2008 to 50 last year he said: "I think the number of deaths doubling in four years is likely to be significant, particularly as the numbers of affected patients seem to be decreasing."

Tear gas barrages

For the past two years, villages outside the capital Manama have often faced near nightly barrages of tear gas. Angry protesters have confronted riot police as violence escalates.

And opposition groups and human rights NGOs have frequently reported that houses are being deliberately targeted by police, a charge the Ministry of Interior rejects.

When Dr Rees was asked about the likely impact of tear gas on a sickle cell sufferer, he told the BBC that because it restricts the supply of oxygen tear gas could trigger severe problems, including the serious complication of acute chest syndrome.

That is a particular risk when canisters are fired into enclosed spaces, such as people's houses.

Although the government denies it does so deliberately, a BBC special report last year found evidence to the contrary.

Human rights organisations and the opposition al-Wefaq society say the practice, which is outlawed by the Geneva Convention, is continuing.

The BBC has seen videos, which cannot be independently verified, that show security forces firing teargas into homes, courtyards and on one occasion a car with women inside. The videos were posted by online anti-government activists.

Frontline hospital

Critics of the government also point the finger at what they say is the decline of health services at the kingdom's main public hospital.

Bahrain has seen more than two years of often violent unrest and the Salmaniya Medical Complex and its medical staff have been on the frontline.

The hospital used to have the reputation of being one of the leading medical facilities in the Gulf, a jewel in the crown of Bahrain's public healthcare system.

But Salmaniya is close to what was an iconic landmark in the capital Manama, Pearl Roundabout. The roundabout was peacefully occupied by pro-democracy activists on 14 February 2011.

Troops guard an entrance to Salmaniya Hospital in March 2011

When security police stormed it in the early hours of 17 February that year, doctors, nurses and paramedics went to the aid of people who had been shot, beaten and tear-gassed.

They staged a protest after word spread that security forces were preventing the wounded from being brought to hospital.

As the government crackdown intensified, doctors from Salmaniya found themselves caught at the sharp end of an increasingly bitter and angry battle between protesters and the police.

On 14 March 2011, Saudi Arabia led a Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) force down a causeway that links the two countries.

Saudi troops took up positions at key installations while police and the Bahrain Defense Force cleared the roundabout, which had been peacefully re-occupied by protesters, using force.

Once again Salmaniya was on the frontline. And two days later the authorities sent the Bahrain Defense Force (BDF) into the hospital. The government said it was forced to take the step because armed protesters were threatening staff and patients. But a doctor who was there told the BBC that claim was "a complete fabrication".

Then beginning in April, 2011 doctors and nurses were arrested in a series of night raids after the introduction of martial law. They were allegedly tortured into giving false confessions and sentenced before a military tribunal, many to lengthy terms in jail.

The impact on Salmaniya was dramatic. The Intensive Care Unit (ICU) where sickle cell patients go for treatment when suffering a sudden attack lost all five of its consultants and one of them is still in jail. An anaesthetist was put in charge of the unit.

Dr Fatima Haji is a rheumatologist who worked at Salmaniya. She was among doctors in Accident and Emergency who assisted the injured from Pearl Roundabout.

She was arrested on the 17 April, 2011 by members of Bahrain's security forces. She was, she says, beaten, threatened with rape and forced to sign a confession she had not read. That confession was used as evidence to convict her before a military tribunal.

Nineteen other doctors who allege similar abuse and being forced to make confessions were convicted by the same tribunal.

Dr Haji was sentenced to five years in jail but was released and has successfully appealed her conviction. She has not been offered her job back at Salmaniya.

Dr Haji told the BBC she attributed the rise in SCD deaths to three factors.

One was the reduction in health services that had resulted from the arrests and prosecution of medical staff, a total of 48 from the hospital.

The second was what she called the "decimation" of the ICU when four of the five consultants were arrested and the fifth fled the country.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, she says that people, even those in acute crisis, are often afraid to come to the hospital for fear of interrogation and arrest.

Despite its heavy use Dr Haji says, exposure to tear gas is "massively under reported".

"A bystander in the street, someone in a house that has been gassed, these are people not involved in demonstrating but still they are afraid they will be interrogated by security at the hospital even before they have received treatment, so they don't come."

Severe SCD episodes, regardless of how they are triggered, need to be dealt with quickly.

"If an acute attack is badly managed, it would increase the risk of death," Dr Rees says.

However without definitive proof, questions remain and Dr Haji acknowledges there is a lack of proper research into CS gas use and SCD deaths.

But even though it can be argued such research is urgently needed, she doesn't believe it will happen: "In the current situation is is not possible to conduct hospital studies. The authorities simply will not authorize it."

Questions asked by the BBC about what research, if any, has been conducted at Salmaniya on the effects of teargas on SCD sufferers have not been answered by the hospital.

- Published22 March 2011