Israel heritage plan exposes discord over West Bank history

- Published

Israel is launching a Year of National Heritage, to coincide with the country's independence day. As part of this push to celebrate heritage, Israel is progressing with a five-year project promoting Jewish ties to ancient sites in Israel and the West Bank. Israel says it is a purely cultural endeavour, which will help save sites from ruin; but Palestinians have criticised it as politically driven - highlighting deep historical differences fuelling the conflict.

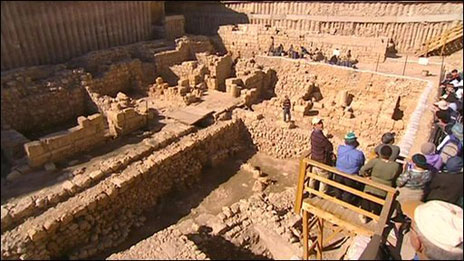

On a peak in the archaeological park of Tel Shilo, finishing touches are being put to a new multi-million dollar visitors' centre, due to open in a few weeks' time.

The rotunda overlooks a rectangular stone outline of what many believe to be the resting place of the Ark of the Covenant, brought here by the Israelites who made Shilo their capital. Excavations there will resume in the summer.

"Who knows what they'll find," says Ncoom Gilbar, a translator who has lived in the Jewish settlement of Shilo, which contains the park, for 22 years. "It's a very exciting prospect."

The ruins scattered around Tel Shilo are testament to the recognition through the ages of its significance as a Biblical site - "it's a whole jumble of periods", says Mr Gilbar.

Behind us, archaeologists and workers delicately excavate the ground around a 4th Century Byzantine church, dusting stones by hand and pushing wheelbarrows of rubble. Nearby stand the remains of an 8th Century mosque, built on top of another, earlier church.

In the past couple of years the number of tourists visiting Tel Shilo has grown exponentially, a trend set to continue since the government designated the park a national heritage site last year.

This means Tel Shilo, along with other ancient West Bank sites, will receive special government funding for their development and upkeep.

"Is there an attempt to bring more people here? Yes," says Mr Gilbar. "Is that wrong? No. This is where our history in the Land of Israel began."

When Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced the $190m National Heritage Sites project, external in 2010, he said Israel's existence depended "first and foremost" on educating future generations about Jewish culture and connection to the land.

"A people must know its past to ensure its future," he said.

'Different layers'

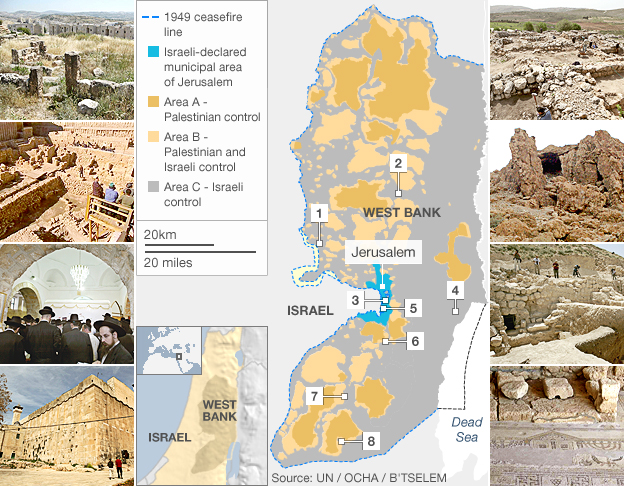

While the vast majority of the places earmarked on the project are in Israel, at least eight are in the West Bank, where many of the events recounted in the Hebrew scriptures took place.

Israel has occupied the area since the 1967 Middle East war, and its designation of sites there as part of its national heritage has drawn criticism.

Israeli national heritage sites in the West Bank

Kiryat Sefer

Site of agricultural village from 3rd Century BC. Contains remains of dwellings, housing what are believed to be Jewish ritual baths, centred around building identified by archaeologists as a synagogue. Village inhabited until 7th Century. Located in the ultra-Orthodox settlement of Modiin Illit.

Tel Shilo

Mentioned in the Bible as site settled by Israelites in 15th Century BC and resting place of Ark of the Covenant. Spiritual and administrative centre of the Jewish people for nearly four centuries. Contains remains from other eras, including Canaanite, Byzantine and Islamic. Located next to the settlement of Shilo.

City of David

Located in the Palestinian village of Silwan in East Jerusalem. Earliest known settlement in Jerusalem, with remains found dating back to 5th millennium BC. Identified by some historians as site of Biblical King David’s palace. Centre of dispute between Jerusalem City Council and Palestinian residents over Israeli plans to develop archaeological park.

Qumran / Khirbet Qumran

Famous as site of discovery in 1947 of Dead Sea Scrolls - earliest known manuscripts of the Bible, dating from 3rd Century BC to 1st Century AD. Site comprises 11 caves and an ancient settlement, widely believed to have been home to a Jewish sect. Remains found include cemeteries and Jewish ritual baths.

Rachel's tomb / Bilal Bin Rabah Mosque

Shrine to the Biblical matriarch revered by Jews, Muslims and Christians. Recognised by Unesco as also the site of the Bilal Bin Rabah Mosque and "an integral part of the occupied Palestinian territories". Located on edge of Bethlehem, on Israeli side of the West Bank barrier.

Herodium

Winter palace of Biblical King Herod, Roman-appointed Jewish monarch who ruled from 37-4 BC. Site declared an Israeli national park in 1985. Sarcophagus discovered there in 2007 identified by archaeologists as Herod’s tomb. Byzantine-era remains also found at site.

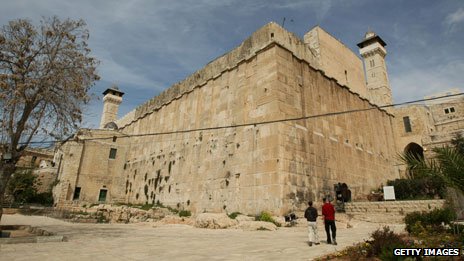

Tomb of the patriarchs / Al-Ibrahimi Mosque

Burial place of patriarchs Abraham, Isaac and Jacob and three of their wives, according to the Bible. Second holiest site in world for Jews. Also revered by Muslims and Christians. Located in Israeli-controlled sector of Hebron. Declared "an integral part of the occupied Palestinian territories" by Unesco.

Susya

Contains remains of synagogue dated between 4th-8th Century, Jewish ritual baths and graves, and an 8th-9th Century mosque. Formerly located within Palestinian village of Susiya, area was declared an archaeological site in 1986 and Palestinian residents in the zone forced to relocate.

"The West Bank is an integral part of the history of Palestine," says Hamdan Taha, director of the Palestinian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. "Netanyahu's heritage plan is an aggression against the cultural right of Palestinian people in their own state," as the West Bank's status is considered to be by many Palestinians.

Mr Taha says the Israeli government's emphasis on the Jewish historical aspect of some sites is "an ideological misuse of archaeological evidence".

"Jewish heritage in the West Bank - like Christian or Islamic - is part of Palestinian heritage and we reject categorically any ethnic division of culture."

According to official Israeli and Palestinian data, there are between 6,000 and 10,000 known archaeological sites in the West Bank, the remains of thousands of years of settlement by civilisations since Neolithic times.

Critics of the heritage plan say Jewish history is only one part, and that Israel is focusing on this to the detriment of other eras.

"If you want to learn about the history of this land, it's about the different layers, the different civilisations that have been here - it's not just about one," says Yoni Mizrachi, a former Israel Antiquities Authority archaeologist.

"Archaeological sites are part of the character of this land and should not be mentioned as something nationalistic - it's beyond that."

The heritage project itself focuses solely on Jewish history but only for a particular educational purpose, the government says.

"These sites are an integral part of our heritage and this is what the programme is intended for - education about our heritage and preservation of the sites' critical importance to our national history," says David Baker, spokesman for the Israeli prime minister's office, which runs the heritage sites project.

Israel says it never discriminates in the field of archaeology, and that detractors are using the issue to undermine evidence of Jewish history in the West Bank.

The Archaeological Department of the Civil Administration (ADCA) - the Israeli body in charge of archaeology in Israeli-administered parts of the West Bank - points to the fact it has unearthed thousands of remains from all periods of settlement, not only Jewish.

It has also opened several non-Jewish archaeological sites, such as the Inn of the Good Samaritan and the Monastery of Euthymius, to the public.

Digging rights

Mr Mizrachi, whose organisation Emek Shaveh opposes the "politicisation" of archaeology, says according to international conventions Israel does not have the right (apart from in exceptional circumstances) to conduct any archaeology in the West Bank.

This is a view firmly rejected by Israel.

"The right of Israel to execute archaeological work in the region is well-embedded in international law and interim agreements with the Palestinians," says Hananya Hizmi, head of the ADCA, which operates according to pre-existing Jordanian law.

The issue is complicated by the fact that there is no single law dealing with archaeology in the West Bank, but rather a series of conventions, inherited laws and treaties.

The main international treaty which governs archaeology in occupied territories is the Hague Convention of 1954, external, which deals by-and-large with the preservation of culturally significant sites. A 1999 protocol, external prohibits archaeological excavation other than essential survey or salvage work, but Israel is among dozens of countries which are not signatories.

With so many sites scattered across the West Bank, the matter had to be addressed when the area was divided up under the Oslo Accords in 1995. Israel and the Palestinians agreed they would be responsible for archaeology in their respective areas, external and set up a joint committee on the issue, but currently there is no archaeological co-operation between the two sides.

'Totally political'

Religious and political sensitivities surrounding the status of ancient sites run deep, and even symbolic adjustments have elicited angry reactions from both sides, deeply suspicious of each other's motives.

.jpg)

The status of holy sites is a highly contentious issue between Israel and the Palestinians

Last year, Israel condemned as "totally political" a successful bid by the Palestinians to get the Church of the Nativity in the West Bank city of Bethlehem listed by Unesco as a World Heritage Site "in Palestine", for the first time.

Two years earlier, Palestinians rioted when Israel added the Tomb of the Patriarchs, known to Muslims as the al-Ibrahimi Mosque, in Hebron, and Rachel's tomb in Bethlehem, to its national heritage list. Both places are venerated by the three major faiths.

"From the Palestinians' point of view, when the Israeli government contributes money to these two sites, which are in the West Bank, they see it as an Israeli attempt to take it all over," says Dr Yitzhak Reiter, an expert in conflict resolution at sacred sites.

"If you invest money in developing and renovating a place, it looks like you have some intention in the future to claim it, and this is a very delicate issue.

"Holy places are being employed by the two parties, each for its own interests. The problem is, as much as they succeed to infiltrate their ideas into society, future reconciliation and compromise become much more difficult to achieve."